The trajectory of Desmond Ackner's judicial career, like that of Frederick Tucker a generation earlier, demonstrated the potential benefits of being seen as a capable and willing legal all-rounder, rather than as an expert in a specialist field. Although Ackner was no intellectual match for his near contemporary Michael Kerr, he had practical experience of a far wider range of cases. The 'Times' reckoned that Ackner was "able to turn his hand to almost any kind of civil work", and it was Ackner, the common law generalist, who progressed to the House of Lords, leaving Kerr, the commercial law specialist, to toil in the Court of Appeal.

Ackner was born in Islington 1920, into an immigrant Jewish family which had come to Britain from Austria before the Great War. His father was a fashionable dentist, with a successful West End practice. Ackner went to Highgate School, then studied law at Clare College, Cambridge, where he overlapped with Kerr. Academically, however, it was not Kerr whom he emulated, but John Donaldson: like Donaldson, Ackner graduated with a lower second. Leaving Cambridge in 1941, he enlisted in the Royal Artillery. But a twisted foot, the result of polio, left him with a life-long limp which ruled him out of front-line service, and he spent most of the Second World War in the Admiralty's legal department. After only just managing to scrape through the Bar examinations (he got a third), Ackner was called to the Bar by Middle Temple in 1945. He joined Chambers in London, but also practised on the Western Circuit, appearing in the local Courts at Bristol, Exeter, Southampton, Taunton, and Winchester.

Notwithstanding his consistently poor performances in exams, Ackner quickly demonstrated that he had the practical skills to succeed at the Bar, and he soon established a busy general common law practice.

Desmond Ackner’s father, Conrad, in professional action, with the artist’s wife posing as his patient.

Within only a couple of years, he was making regular appearances in the law reports across a broad cross-section of civil litigation, including child welfare, divorce, industrial accidents, landlord and tenant, local government, personal injuries, planning, roads and highways, and tax. He also made occasional appearances in the criminal courts, although crime was never a significant part of his practice. Ackner was a talented and effective advocate, and solicitors trusted him to handle sizeable cases on his own. From an early stage, he appeared without leaders in the Court of Appeal. In Shelley v London County Council [1949] AC 56, he argued a three day appeal in the House of Lords after only three years in practice, an eye-catching professional achievement. (Ackner lost, but it was a near thing: the Lords were divided three to two.)

Ackner achieved this precocious courtroom success in spite of a lack of physical presence. By contrast with the strongly-built Kerr or the six foot tall Donaldson, he was a relatively small man. But he had powerful voice projection, and clarity of expression. Importantly, he was also blessed with boundless self-confidence, which can help lend authority to an advocate, and which enabled him to bounce back even when cases were going badly. Ackner's style of delivery was generally concise and to the point, although he had a reputation for sometimes adopting theatrical language. Dogged and determined in pursuing his client's case (Kerr recalled a blazing post-hearing row in which he and Ackner, instructed on opposite sides, bandied insults and mutual accusations of gross misconduct), he was a robust cross-examiner when the case demanded. He proved himself equally adept whether presenting a case to a jury or debating a point with a Judge. Commercial law was not a major feature of Ackner's career as a junior barrister. He began to feature in Lloyd's Law Reports cases in the 1950's, but his early appearances were almost all in personal injuries cases: in this quietest of periods for commercial litigation, the volumes of Lloyd's reports were routinely padded out with repetitive cases about crewmen and stevedores falling into ships' holds or tripping over things on docksides. A single reported international sale of goods case appears to have represented the full extent of Ackner's engagement with the Commercial Court during this part of his career.

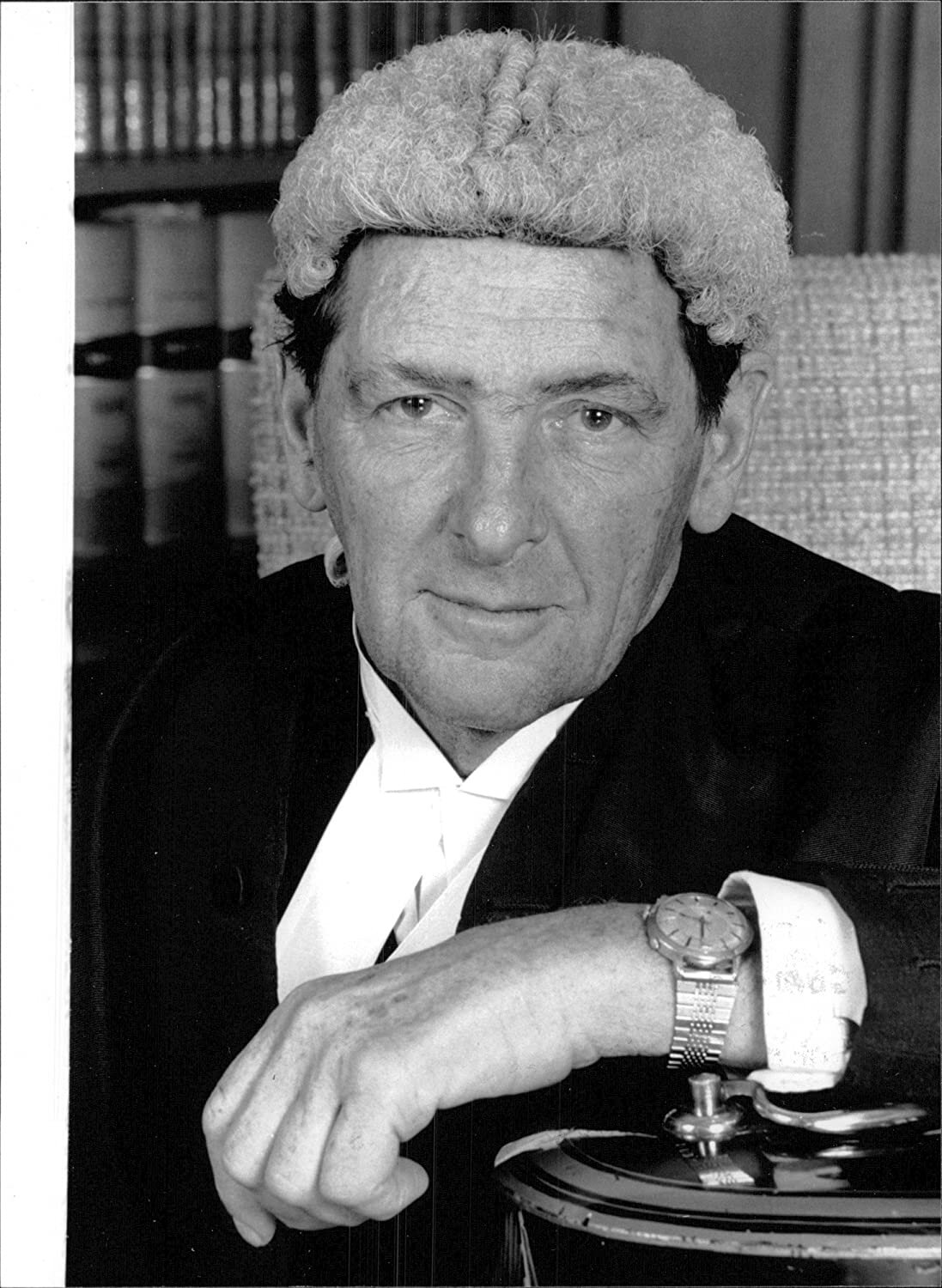

Ackner as a newly-appointed QC, in 1961.

Ackner was appointed Queen's Counsel in 1961. As leading counsel, he added libel litigation to his repertoire. He acted for John Bloom, a "washing-machine tycoon" (and gnarled veteran of two "washing-machine wars") in an action against The 'News of the World', and, switching to the side of the press, acted for the defence in a claim by Prime Minister Harold Wilson. His libel clients also included Joseph Stalin's daughter and the Prime Minister of Singapore. Big libel cases attracted press coverage, and Ackner's new field of work brought him to the attention of the public. So did his involvement in the litigation which resulted from the disastrous side-effects of the morning sickness pill thalidomide (Ackner represented the victims; Kerr was retained by the manufacturers. The case settled. The two future Commercial Judges had become friends by this stage.) But Ackner's highest-profile instruction was as counsel for parents and residents of Aberfan at the public inquiry into the collapse of a spoil heap onto a Welsh village primary school on an October morning in 1966. 116 children and 28 adults had been killed. Ackner was at his most combative in his sustained attack on officials of the Coal Board, and in particular the Chairman, Lord Robens. (When Ackner became a peer two decades later, Robens refused to speak to him whenever their paths crossed in the Palace of Westminster.)

In cases less well-known to the public, but of more long-lasting legal significance, Ackner failed to convince the Privy Council not to change the law of remoteness in nuisance in The Wagon Mound (No 2) [1967] 1 AC 617, but convinced the House of Lords in Ridge v Baldwin [1964] AC 40 that the dismissal of the Chief Constable of Brighton was null and void because it was ultra vires. Ridge was one of the foundational cases of the modern law of judicial review, while Ackner snatched victory from defeat in The Wagon Mound (No 2) by winning his alternative case in negligence. He achieved this by, in effect, persuading the Privy Council that its earlier decision in The Wagon Mound (No 1) [1961] AC 388 had been based on false premises.

Ackner also raised his profile in commercial work, although it never became a mainstay of his practice. Onassis & Calogeropoulos v Vergottis [1968] 2 Lloyd's Rep 403 had shades of modern oligarch litigation, the dispute being about whether a large sum of money which Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis had handed over in lamentably informal circumstances had been intended as a loan or the price of a ship. (Onassis's co-plaintiff, Ms Calogeropoulos, was his then life-companion, better-known as opera diva Maria Callas.) Ackner was brought in when the case reached the House of Lords, to try to persuade their Lordships to accept the implausible proposition that trial Judge Eustace Roskill had made such a mess of the case that there should be a re-trial. The majority of the Law Lords were not so credulous, although Ackner came close to success, with a three-two split. Ackner also appeared in a handful of banking and insurance cases. He was again brought in at the appeal stage in The 'Tojo Maru' [1969] 2 Lloyd's Rep 193, a major salvage dispute. Ackner won in the Court of Appeal, only for the victory to be dashed in the House of Lords: [1971] 1 Lloyd's Rep 341. But he did not argue this case in the Lords: the day before the appeal began, he had taken office as a High Court Judge.

Ackner during his time in the Court of Appeal.

Ackner had acquired significant part-time judicial experience during the 1960's, through appointments as Recorder of Swindon in 1962 and as an appeals Judge for Jersey and Guernsey in 1967. He had also been active in Bar politics, and had been Chairman of the Bar Council from 1968-1970. For many years, holders of this post were more-or-less routinely offered a place on the Bench at the end of their term, so Ackner's elevation to the Queen's Bench Division in January 1971 came as no surprise. In the early years of his judicial career, Ackner dealt confidently with cases in a variety of Queen's Bench areas, including administrative law, planning, tax, and, in particular, personal injuries and crime. A severe Judge in criminal matters, he was known to grumble about statutory limits to the lengths of the sentences which he could impose. Like Clement Bailhache, he was particularly irritated by defendants who insisted on wasting everybody's time by pleading not guilty when their guilt was perfectly plain to the Judge. Unlike Bailhache, however, he managed to keep his thoughts to himself until after the jury had returned a guilty verdict.

Ackner was added to the roster of Commercial Court Judges in 1973, and heard about twenty reported cases in the Court over the next seven years. His decision in The 'Darrah' [1974] 2 Lloyd's Rep 435 is still cited by text-books in relation to voyage charter clauses dealing with congestion, and he presided over substantial litigation in The 'Zographia M' [1976] 2 Lloyd's Rep 382, a major time-charter case which lasted a month, and Vosper Thornycroft v Ministry of Defence [1976] 1 Lloyd's Rep 58, which turned on the interpretation of the payment provisions of a major shipbuilding contract for a new class of frigates for the Royal Navy. But Ackner was little given to profound meditations on the principles of English commercial law, and no significant legal developments emerged from his time in the Court. He was, however, a very good trial Judge, and sufficiently sound as lawyer that his judgments were usually upheld if they reached the Court of Appeal.

Away from the Commercial Court, Ackner shared with John Donaldson the distinction of being the subject of a House of Commons motion demanding his dismissal. This was the result of his issuing injunctions against secondary picketing during the 1978-1979 "Winter of Discontent". When Labour MP's moved that Ackner should be sacked, Conservatives countered with an amendment praising his judicial talent. Ackner's judicial career survived, and he was promoted to the Court of Appeal in 1980. As a Lord Justice, he was again involved in contentious trade union cases. But he also sat in a significant number of shipping appeals, including The 'Good Helmsman' [1981] 1 Lloyd's Rep 377 and The 'Antiaos' (No 2) [1983] 2 Lloyd's Rep 473, both concerning withdrawal of time-chartered ships for non-payment of hire, and The 'Evia' (No 2) [1982] 1 Lloyd's Rep 334, which went to the House of Lords (who agreed with Ackner) and remains the leading case on safe ports. He also heard appeals in Admiralty, insurance and sale of goods cases, and sat on a number of appeals concerning the scope of the recently-invented Mareva Injunction. Overall, he was more heavily involved in commercial cases in the Court of Appeal than he had been at first instance. He was also prominent in criminal appeals, and sat in cases involving a range of other areas of law, including employment, landlord and tenant, personal injuries, planning, tax, and tort.

In early 1986, there were two vacancies for common lawyers in the House of Lords. Michael Kerr, who hoped (in vain) that he might secure one of them, thought that Ackner was the automatic choice for the other, because of his all-round versatility. Kerr's prediction was correct, and Ackner duly became a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary. Henry Brandon was by now established as the senior commercial lawyer in the Lords (Kenneth Diplock had died, and Eustace Roskill had retired, not long before), and Robert Goff arrived soon after Ackner. These two, whose intellectual abilities and commercial experience put Ackner's in the shade, tended to take the lead in commercial appeals during Ackner's time, and he made little impression on commercial law in the highest Court. His most enduring judgment was The 'Simona' [1989] AC 788, in which he analysed the significance of "acceptance" (or of failure to accept) of a repudiatory breach of contract. His much-debated decision in Walford v Miles [1992] 2 AC 128 that an "agreement to agree" is not legally binding, also had significant implications in the commercial field.

Ackner in 1990, while a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary.

Although Ackner proved a relatively anonymous Law Lord in commercial cases, he made a splash elsewhere. In Spycatcher [1987] 1 WLR 124, he was a member of the majority which upheld an injunction restraining newspaper publication of extracts from Peter Wright's account of his supposed activities in MI5. Showing flashes of the moral indignation which had often characterised his performance as a criminal Judge, Ackner held that the fact that much of the book was already in the international public domain was no reason for not ordering an injunction when it had been written in breach of Wright's employment obligations. Ackner garnished his judgment with criticism of several newspapers, sparking a low-level feud with the press which rumbled on for several years.

Ackner retired from full-time judicial office in 1992, although he continued to sit quite frequently as a House of Lords "retread" for another four years. Away from the Bench, he sat as an arbitrator and as a member of various disputes and appeals panels in the City of London. He also used his seat in the Lords to speak in the occasional debate. Generally suspicious of any suggestions for reform of the judicial system or the legal professions, he attacked the proposals of successive Conservative and Labour governments with equal gusto. Retirement also gave him more time for his favourite pastimes of reading, theatre, and gardening at his home at Sutton, in Sussex, where he also liked to use the swimming pool daily, regardless of the weather.

Ackner married Joan May Spence in 1946. Joan was a widow, and Ackner became stepfather to her daughter. They later had a son, and another daughter, Claudia, who followed her father in becoming a barrister, a member of the Western Circuit, and a Bencher of Middle Temple. She was appointed as a Circuit Judge in 2008.

Desmond Ackner died at St Thomas's Hospital in London in March 2006. Serving and former Lords Chancellor who had felt the force of his outspoken public criticism were among the enormous number of legal dignitaries who attended the memorial service in Temple Church.

“To those who criticise the length of this inquiry, I would reply that if they had dug with their own hands for their own children, they would recognise with bitter clarity the need for the closest scrutiny of every detail to ensure that this should never happen again.”

Ackner’s role in the Aberfan Inquiry is remembered in the Memorial Garden on the site where the Pantglas Junior School once stood.