Joseph Walton's fifteen-year connection with the Commercial Court began in spectacular glory, as the dominant leading counsel in the Court's first five years, but ended in disappointing anti-climax, with an early death and a reputation as an indecisive Judge who failed to live up to expectations.

Walton was born in Liverpool in September 1845. His father, also Joseph, was a local merchant. He was a prosperous one, to judge from the fact that the family lived at Fazakerley Hall, in an area which now lies well within the metropolis, but had a rather more rural aspect in the 1840's. Fazakerley is to the north-east of Liverpool's Walton district, which has a history traceable to Norman times (when it was a country estate), and which was presumably the source of the family name. The family were Roman Catholics, and Walton, the eldest son, received a Catholic education in Liverpool and then at Stonyhurst College. He studied mental and moral science at the University of London, where he was awarded a first class degree, joined Lincoln's Inn in 1865, and was called to the Bar in 1868. Walton joined the Northern Circuit, in order to practise in his home city, and was a pupil of Charles Arthur Russell while Russell was making his name as a Liverpool junior. Perhaps it was Russell, himself the author of a handbook to the working of the Liverpool Passage Court, who inspired Walton to write a guide to the practice and procedure of one of the important local courts which flourished in the North of England at the time. Unfortunately, Walton chose to write about the Lancaster Court of Common Pleas, which was promptly abolished by the Judicature Acts.

Up to this point, Walton's path had been strikingly similar to that of his future Commercial Court colleague, John Bigham. Bigham was another son of a Liverpool merchant family who returned to his roots to start his career and forged links with the future Lord Chief Justice. (Bigham was five years older, but, by extending his student career, he allowed Walton to overtake him: Bigham was not called to the Bar until 1870.) But the parallels did not continue into the two men's early years in practice. Bigham achieved virtually instant success, but Walton found the Bar altogether slower going. He filled up some of his free time as one of the earliest editors of The "Annual Practice", as The 'White Book" was then known.

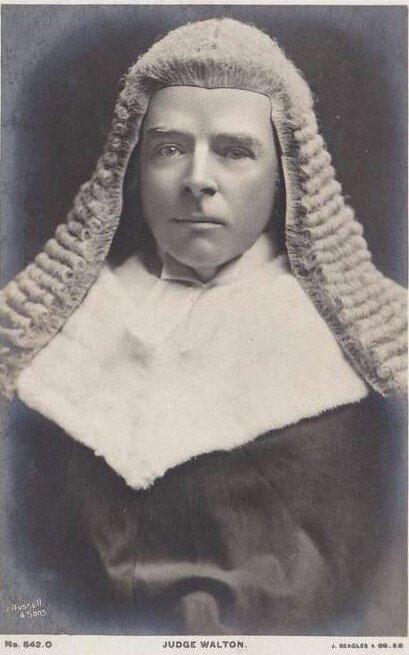

Walton signed this image in 1905, although it is not clear when the photo was actually taken.

Walton seems to have spent the first decade and a half of his career more or less exclusively as a Liverpool “local”, without being instructed in the London cases which made it into the law reports. When he did eventually appear in a reported case, it was not in the commercial field which would eventually dominate his career, but in an action to determine liability to contribute to the expenses of maintaining the highway. But the local Liverpool courts had a good quantity of commercial work in the 1870’s and 1880’s, and Walton must have acquired some specialist commercial experience there, because he began to appear in reported shipping and marine insurance cases in the later 1880's. Most prominently, he was Russell's' junior in Hamilton v Pandorf (1887) 12 App Cas 518, an important House of Lords decision on the scope of "perils of sea" in a contract of carriage. (Russell and Walton they lost the case, to Bigham, who was already a QC, and J.C. Mathew's star pupil, and future Admiralty Judge, John Gorell Barnes.) But he was not yet a pure commercial specialist. He was also instructed in cases about insolvency, nuisance, rates, title to land, and landlord and tenant. His most eye-catching case as junior counsel was Barnardo v McHugh [1891] AC 388, an application for habeas corpus in which the underlying legal issue concerned the custody rights of parents who had surrendered their children to Dr Barnardo's charity.

Walton was appointed Queen's Counsel in 1892. He was away from London on Circuit at the time (a reflection of the fact that his practice was still a mixed one), and had to wait until October before he was formally called to the inner Bar at the Law Courts. At forty-seven, he was comparatively old, and the twenty-four year wait was twice as long as it had taken Bigham, his fellow Liverpudlian, near-contemporary and professional rival. But Walton was fast catching up with Bigham. By this stage, his practice was more or less exclusively commercial, to judge from reported cases. He had been led by future Commercial Judges Charles Russell, William Kennedy, Richard Henn Collins, and Walter Phillimore, as well as by Bigham himself and by John Gorell Barnes. He had also argued cases on his own in the Queen's Bench, the Admiralty, and the Court of Appeal. From the moment that he became a QC, he was instructed in an almost continuous stream of bill of lading, charterparty, and marine insurances cases. (He did occasionally find time to take on other work, usually with a Liverpool connection: election disputes, local government, and even a food hygiene case.)

“A lawyer on the Bench”: ‘Spy' shows the cheery side of Walton’s nature, around a year after he became a Judge.

Non-lawyers sometimes confused Walton with John Lawson Walton, QC and MP, who was no relation, or with Joseph Walton MP, who was not a lawyer at all. But the legal world increasingly knew who he was, and recognised his abilities. Like Bigham, Walton's style of advocacy emphasised clarity rather than theatre (The 'Times' thought that his approach was almost "conciliatory" in comparison with the grandstanding gladitorial style often seen in criminal trials of the day), and he was persuasive rather than forceful. This was in keeping with a time when jury trial was increasingly becoming less common in commercial cases. In fact Walton, with perfect timing, was reaching his peak as a specialist commercial practitioner just as the Commercial Court was launched in 1895. It was an important year for him, since he also became Recorder of Wigan, a part-time criminal judicial appointment and a good springboard for a career on the Bench. In the Commercial Court, Walton seized his opportunity in the new tribunal which had been created to deal with the sorts of case in which he specialized. In the first volume of The 'Reports of Commercial Cases', covering the period from March 1895 to July 1896, he made thirty-five appearances to Bigham's sixteen. No-one else had more than ten. Walton maintained his commanding lead over Bigham the following year. After Bigham became a Queen's Bench Judge in October 1897, no other Commercial Court practitioner came anywhere near Walton. In 1897-1898, when Walton made twenty-five appearances in 'Commercial Cases', his closest rival made only six. That was Hugh Fenwick Boyd QC, who died in July 1898 aged forty-six, further clearing the field for Walton's absolute dominance.

Probably no Commercial Court practitioner since has secured such a pre-eminent position as Walton did in those first years. And of course he was also instructed in the higher Courts: in 1900 alone, he argued half a dozen cases in the House of Lords, and he appeared in more than thirty Lords cases as a QC. Among commercial cases, they included Glyn v Margetson [1893] AC 351 on the limits of a "liberty" clause in a contract of carriage (and a significant authority on the importance of construing contractual terms in context); and the final appeal in Rose v Bank of Australasia [1894] AC 687, the case which became, in a legend created by T.E. Scrutton, the cause for for the creation of the Commercial Court, after the first-instance Judge, John Compton Lawrence, who knew absolutely nothing about commercial law, made a monumental mess of the trial.

Walton was almost exclusively a commercial specialist at the height of his success, but not quite. His outstanding reputation inspired clients to seek his services for less familiar areas of litigation, and his Lords appeals included cases about copyright, health and safety, tax, and utilities. In Powell v Kempton Park Racecourse [1899] AC 143, he argued before no fewer than ten Law Lords. This was one more than had heard the appeal in the great tort and industrial relations case of Allen v Flood [1898] AC 1 a year before, and the assembly included not only the Lord Chancellor of Ireland (Lord Ashbourne) but also Lord Arthur Hobhouse, who was a veteran of Privy Council appeals (and ancestors of a future Commercial Judge) but almost never sat in the Lords. The inflated Bench would suggest that grave legal issues of the utmost national importance were at stake. In fact, the issue in Powell was whether or not the activities of bookies in the public enclosure at Kempton Park contravened the Betting Acts. Perhaps the high turnout of Lords reflected the degree of judicial enthusiasm for equestrian matters. Walton (who won the case) did not much care for horseracing himself, although he became standing counsel to the Jockey Club in succession to the horse-obsessed Charles Arthur Russell. (Russell was the trial Judge in Powell, but both the Court of Appeal and the Lords thought that he had got it wrong.)

Walton was not just stunningly successful, he was also much-liked. He was elected Chairman of the Bar in 1898, a clear sign of the affection and regard in which he was held by his fellow professionals. Elevation to the Bench looked like a foregone conclusion, and Walton's appointment was widely anticipated. The list of new KC's which was appointed in early 1901 was particularly strong (it included future Commercial Court Judges T.E. Scrutton and J.A. Hamilton). There was a general suspicion that this was partially a result of ambitious juniors positioning themselves to fight for a share of Walton's practice when he left the Bar. They did not have long to wait. Walton joined the King's Bench (newly-retitled, after Queen Victoria's death earlier that year) in October 1901. He replaced J.C. Mathew, the first Commercial Judge, before whom Walton had appeared more frequently than anyone else in the Commercial Court, and who had been promoted to the Court of Appeal. Mathew and Walton were sworn into their new offices together by the Lord Chancellor, Lord Halsbury (in private: judicial investitures were not public events in those days). The legal press welcomed Walton's appointment, though parts of the national press, still struggling to distinguish Walton from his namesake in the House of Commons, deplored what it believed to be a severe loss to Parliament. The most outstanding commercial barrister was naturally expected to make an excellent Judge, and most observers would probably have taken it for granted that Walton would reach the Court of Appeal himself one day. He almost got there sooner than he might have expected. When Lord Chancellor Halsbury presented Prime Minister Lord Salisbury with his proposal to make Mathew a Lord Justice of Appeal and replace him with Walton, Salisbury muttered darkly about appointing Walton direct to the Court of Appeal over Mathew's head: the Evicted Tenants Commission still had the potential to cast a shadow over Mathew's career.

In the event, Halsbury had his way, and it was Mathew who went to the Court of Appeal in 1901. Walton never did get there. In his nine year judicial career, he handled a range of King's Bench business, including company law, landlord and tenant, licensing, local government, and tax, as well as the commercial cases, with which he was more familiar. He was by no means a bad Judge. In fact he was a very good one. For example, a substantial proportion of his reported judgments related to crime. This was an area of which he had had relatively little experience before going on the Bench, yet he handled the work well. But, overall, Walton never managed as a Judge to fulfill the expectations which he been generated by his career at the Bar. Probably he never could have done: to be as successful on the Bench as he had been at the Bar, Walton would have had to have been the best Commercial Judge of all time, better than Mathew, and Mathew was peerless. But even allowing for that, Walton's judicial performance was disappointing. Like Kennedy, he was inclined to be painstaking, remorselessly but ponderously working his way through every point. But, more than that, he was perceived to be indecisive. Mathew and Bigham, altogether less sensitive characters who seldom experienced any difficulty in making their up their minds, tended towards the view that what parties to litigation most wanted from the trial Judge was a clear and prompt decision: if anyone thought that the Judge had got it wrong, that was why there was a Court of Appeal. But Walton somehow lacked the confidence to risk getting things wrong. He sometimes worried about reaching the right decision right to an extent which made it difficult for him to reach any decision at all.

An undated photograph hinting at the more anxious aspect of Walton’s personality.

This shortage of self-confidence perhaps explains why Walton spent much of his judicial time in the Court of Criminal Appeal (where the Judges sat in threes) or in Divisional Courts (where there was always at least one colleague to share the decision-making burden). In contrast to his Commercial Court-centred practice in his heyday at the Bar, a surprisingly small proportion of Walton’s reported judgments were commercial in nature.

But the legal profession recognised Walton’s merits as well as his faults. He was patient, and he had a reputation for courtesy to which Mathew and Bigham could not always lay claim. His knowledge and understanding of the law were universally acknowledged, and he was not gripped by indecision in every case. When he did struggle, he received credit for being conscientious, even if litigants and lawyers sometimes wished that he could be conscientious more quickly. Joseph Walton was an exceptionally popular Judge. The legal world was appalled when he died, relaxing in an armchair after dinner, at his country home in Suffolk, in August 1910. He was not quite sixty-five. The cause of death was probably heart failure. Walton had been receiving treatment for a heart condition for some time. But there had been no indication of any worsening in his health: he had been sitting normally in Court, had recently completed editing the entry on "Estoppel" for "Halsbury's Laws of England", and, only the previous week, had presented a paper at the annual meeting of the International Law Association and chaired the meeting’s session on General Average. Walton died during legal vacation, and most of legal London had left town for the summer. But Sir Samuel Evans, President of the Probate, Divorce & Admiralty Division, who had been left behind as Vacation Judge, paid tribute to his late colleague in open Court.

Walton had decided his most prominent commercial case a few months before his death. In Kish v Taylor [1910 2 KB 309, a ship put to sea with so much cargo loaded on the deck as to make it unstable and unseaworthy, in breach of charterparty. The Master was forced to divert to a port of refuge to restow the cargo, delaying the voyage. Walton held that, since the diversion had in fact been necessary for the safety of the ship, it was not an unjustified deviation which had the effect of terminating the charter, even though it was caused by the owners’ breach. The decision was overruled by the Court of Appeal ([1911] 1 KB 625), but Walton was posthumously vindicated by the House of Lords ([1912] AC 604).

Joseph Walton had married Teresa D'Arcy in 1871. Teresa's Irish grandfather, Martin Burke, had achieved public prominence in a legal context in 1849 when he, alone among the jury, had refused to convict the defendants in a highly-publicised Dublin sedition trial. The Waltons had eight sons and a daughter. One of the sons, Alexander, became a Catholic priest, and conducted the Requiem Mass for his father at St James's, Spanish Place, where the family had worshipped. Walton was buried in the Roman Catholic cemetery at Kensal Green.

In such spare time as he had, Walton was active in Roman Catholic charities. He was also, like Arthur Channell, a keen yachtsman, although, since Walton did his racing in Suffolk while Channell's base was Cornwall, it may be that they never competed against one another.