J.C. Mathew aged 10.

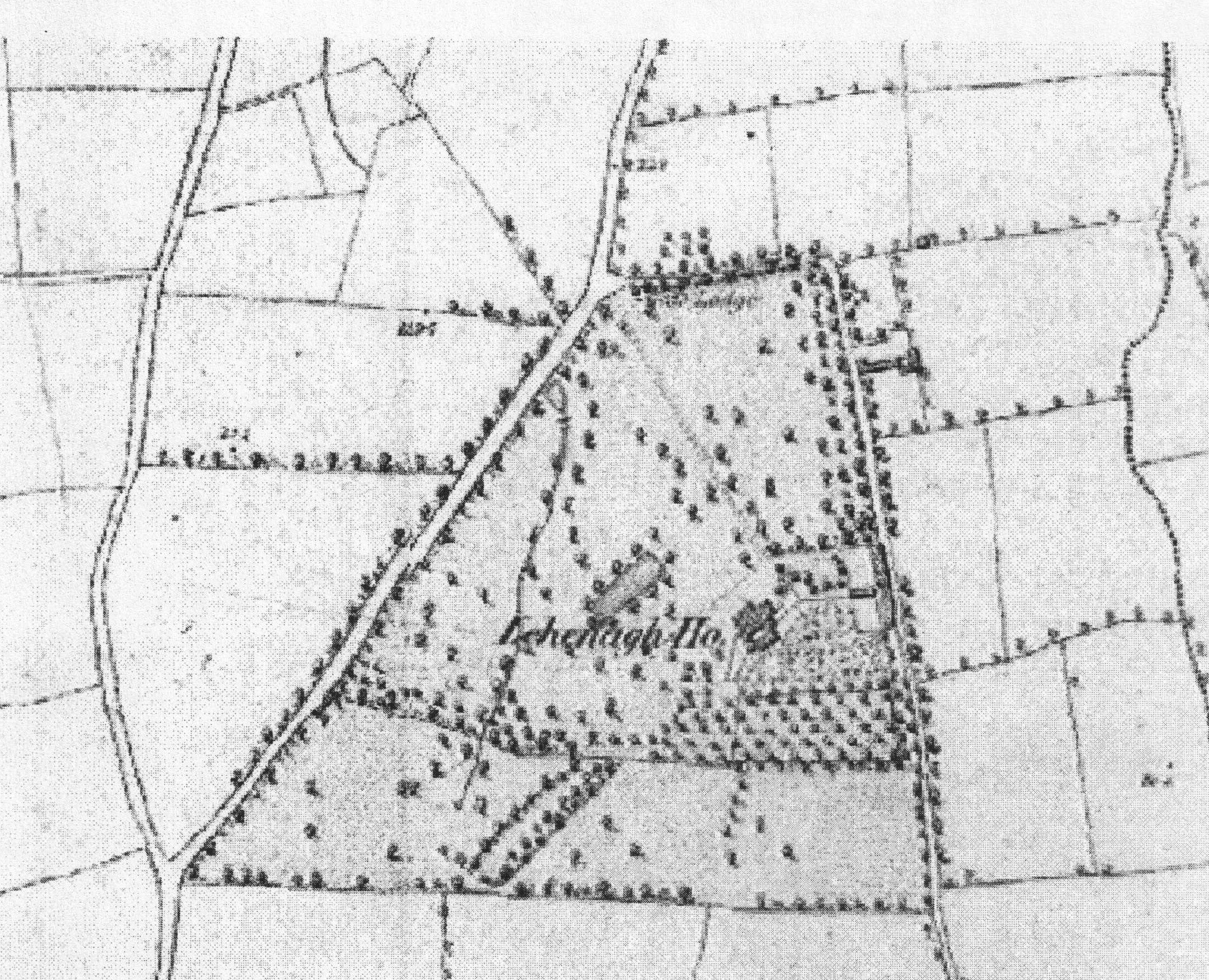

Accounts differ about whether the first Commercial Court Judge was born at his family's home, Lehenagh House, to the south of Cork, or in Bordeaux. The 'Dictionary of National Biography' and Mathew's 'Times' obituarist both thought Cork. But The 'Dictionary of Irish Biography' and Mathew’s legal obituarists were better informed, for Mathew’s parents, Charles and Mary (née Hackett) spent time on the Continent while Charles attended to business interests, and their first child was delivered in the South West of France, in the summer of 1830. But he grew up at Lehenagh, and was educated at a private school in Cork.

The Mathew family originated in Llandaff and Radyr, in South Wales. The Irish branch was established in the 17th Century, and became substantial landowners in Cork, Galway, and Tipperary. Charles owned property around Lehenagh, which his eldest son eventually inherited. The sources give no indication of the nature of Charles’s Continental business affairs, describing him only as a "gentleman". But it is safe to assume that neither Charles nor any of his close relatives had any professional connection with the law, because his part of the family was devoutly Roman Catholic, and the legislation which officially opened public life and the professions to Catholics after generations of exclusion was completed only in 1829. It took even longer for the practical effects of the Catholic Emancipation Acts to sink in, and J.C. Mathew's acceptance as a student by Trinity College Dublin in 1845 was still exceptional for the times. It was said that the celebrity status of his uncle, the Catholic priest and temperance campaigner "Father Mathew" (Theobald Mathew), whose popular appeal transcended sectarian boundaries, played a part.

A brilliant student, Mathew excelled in Ethics & Logics, and graduated with prize-winning success. His initial plan appears to have been to join the Irish Bar, for he was admitted to the King's Inns, Dublin, in 1850. But Mathew soon took the risky and brave decision to seek his fortune in England, where he had no roots. Mathew later often holidayed in Ireland with his family, but he never again made it his permanent home. However, he always retained a love for his native land, always took an interest in Irish affairs, and was a lifelong supporter of Irish Home Rule. According to The ‘Law Times’, Mathew even once stood as a Parliamentary candidate for an Irish constituency. The 'Solicitors' Journal' called him, affectionately, "Irish of the Irish".

Mathew was admitted to Lincoln's Inn on a scholarship in 1851. He studied in the Chambers of two eminent but contrasting legal professionals. Thomas Chitty, member of a famous legal family (his father had been one of the leading legal writers of his time; his elder brother was the original author of 'The Law of Contracts', which remains the principal practitioners’ text on the topic; and one of his sons became a Chancery and Court of Appeal Judge) was a special pleader. So complex were the technical rules of pleading before the Judicature Acts of the 1870's that pleading was regarded as a learned profession in itself. Chitty and similar specialists made a good living without ever going to Court in the cases for which they drafted pleadings, or even providing advice. The dozens of trainee lawyers who passed through Chitty's pupil-room in King's Bench Walk included future Lords Chancellor Hugh Cairns and Farrer Herschell, as well as Mathew's other mentor, James Shaw Willes. In contrast to Chitty, Willles was very much the practising barrister, a successful commercial law specialist who later became a hugely respected Judge of the Common Pleas. Like Mathew, he was Cork-born (his grandfather had been Mayor of the city) and a graduate of Trinity College. It must have been from Willes that Mathew acquired not only an enthusiasm for commercial work, but also an interest in civil procedure. Willes was an acknowledged expert in the subject, and had been prominent on the commission whose work led to the Common Law Procedure Act 1850.

Mathew’s uncle Theobald, “Father Mathew”, was a revered temperance campaigner whose appeal crossed the religious divide.

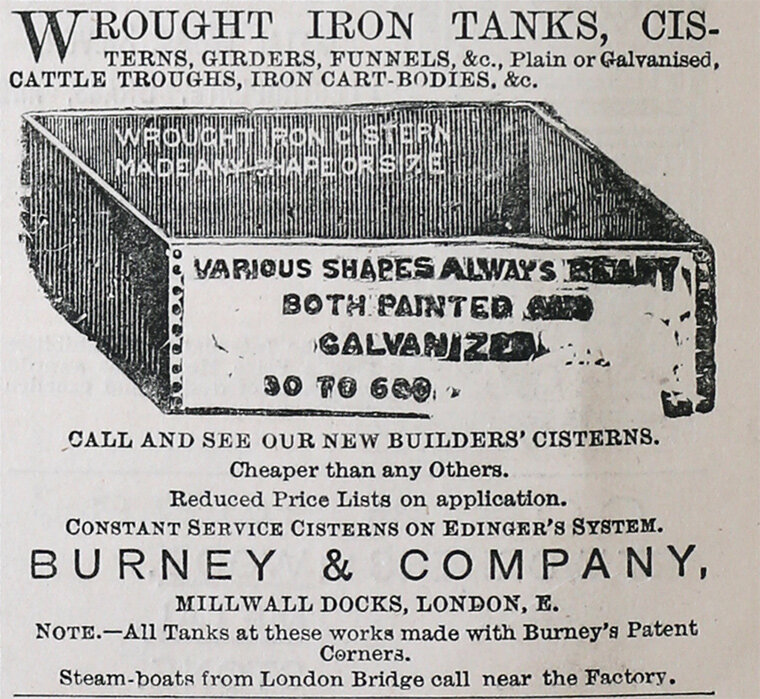

The Chitty and Willes families became connected by more than their shared link with J.C. Mathew when Willes' younger sister married Thomas Chitty’s son. In March 1895, their son, Thomas Willes Chitty, appeared before Mathew as junior counsel for the successful plaintiff in Burney v Elliman, the first Commercial Court trial. (Thirty years later, T.W. Chitty caused a minor sensation in the legal world by resigning as a Master of the King’s Bench to return to practice at the Bar.)

After completing his apprenticeships with Chitty and Willes, Mathew was called to the Bar in 1854. Without family connections to either London or the law, he was dependent for success upon his talent and determination. These were considerable, but, to begin with, they were not enough. Like many commercial barristers after him, Mathew went for years with very little work. He used some of his spare time profitably by honing his forensic skills in the Hardwicke Society, a Bar debating society. Mathew was a founding member, and the first Honorary Secretary.

James Shaw Willes left his native Ireland to become a barrister in London, was successful in commercial practice without becoming Queen’s Counsel, and was a great commercial Judge. His pupil, J.C. Mathew, followed the same career path.

It took Mathew the best part of a decade to establish himself. His first reported case was Temperley v Willett (1856) 6 El & Bl 380, a dispute arising out of an altercation in the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden: Mathew's application on behalf of the plaintiff for inspection of a document was dismissed on the grounds that his client only wanted the document for use in another action, which was an impermissible purpose. His name did not appear in the law reports again until 1861. But when success finally arrived, it was spectacular: The 'Law Times' said that "it has rarely fallen to the lot of any barrister to acquire such a monopoly of the choicest and most lucrative work", while The 'Times' thought that no commercial practitioner who came after him enjoyed such a dominant position as Mathew did between 1865 and 1881. Mathew appeared in more than 100 reported cases in that period. Virtually all of them related to shipping, insurance, sale, and other commercial transactions. In 1880, his last full year at the Bar, Mathew made a dozen appearances in the law reports, including two cases in the House of Lords and two in the Privy Council.

Among prominent cases which are still cited today are Bowes v Shand (1877) 2 App Case 455 on contractual construction; Simpson v Thomson (1877) 3 App Cas 279, a foundational case for the principle that economic loss consequential on damage to someone else's property is not actionable in negligence (and authority, should it be needed, for the proposition that a shipowner cannot sue itself); De Bussche v Alt (1878) 8 Ch D 286 on the requirements for a valid settlement or release; and Glyn Mills Currie & Co v East & West India Dock (1886) 6 QBD 475, which established the right of a shipowner to deliver against any one of a set of bills of lading (Mathew went on the Bench before the decision of the Court of Appeal was upheld in the House of Lords).

Mathew was said to have appeared on 600 summonses before Masters or Judges in a single year, earning 1,200 guineas from that work alone. It was a formidable income for a junior barrister, and it did not include his fees from trials or paperwork. Mathew became Junior counsel to the Society of Lloyd's, and was instructed in virtually every major City of London commercial case tried at the Guildhall. The only commercial junior of the time who approached his success was his friend Charles Bowen. But not even Bowen obtained such a grip on the best commercial work. Half a century later, T.E. Scrutton, one of Mathew's most eminent successors as Commercial Judge, regaled law students with tales of Mathew rushing from Court to Court, passing instructions to various different leaders as several of his cases were tried simultaneously.

For all of his dominance of his chosen field of practice, Mathew did not become a leader himself. This cannot have been for lack of technical ability. Mathew's extensive debating experience, and his fame as an entertaining after-dinner speaker, show that he was eloquent and could hold an audience, while all of those summonses would have given him plenty of practical advocacy experience, and he was sufficiently skilful to be praised by the House of Lords for his "able argument" in Steel v State Line (1877) 3 App Cas 72, a seaworthiness case in which Mathew argued part of the appeal as junior to the great Arthur Cohen QC. Perhaps, finally secure in the success of his junior practice after a difficult start, he simply saw no need to take a risk by moving to the front row. The step-change between the work of junior and senior counsel was far more marked in Mathew's day than now, and not every busy junior who became Queen's Counsel made a successful transition. It was also said that Mathew worried about his husky voice being too weak for trial advocacy. Arguing a summons in Chambers before the Master or Judge, or even arguing points of law in the Court of Appeal, as Mathew did without a leader in several cases, was one thing. But Mathew practised in an age when jury trial was still the norm, even in commercial cases. The fashion of the day was for a style of advocacy which was at least forceful, if not downright theatrical. When Mathew, delegating for an unwell Lord Chief Justice Russell, delivered the address on the Lord Mayor's visit to the Law Courts in November 1897, The 'Times' complained that no-one could hear what he was saying. A lack of voice projection would certainly have been a handicap for a commercial QC of the 1870's.

Although Mathew did not acquire a reputation as an outstanding advocate, he did, like Willes, become known for his knowledge of civil procedure. Knowledge did not mean affection. Mathew shared with Charles Bowen a conviction that the indiscriminate imposition of Chancery procedures on all common law litigation after the Judicature Acts often caused unnecessary delay and cost. Although Mathew was a capable black-letter lawyer, his approach to commercial litigation was primarily practical. His method was to identify the real issues in the case, concentrate on those, and more or less ignore anything else. He recognised that, unlike heavyweight Chancery litigation, most common law actions turned on at most a handful of fairly discrete points. He was convinced that lengthy pleadings, further and better particulars, disclosure, and interrogatories often obscured what a common law case was really about, instead of illuminating it.

In early 1881, Bowen, already a Queen's Bench Judge, and Mathew were appointed to the Legal Procedure Committee, which had been established to review practice and procedure in common law cases. The Committee analysed Court statistics to show that the vast majority of Queen's Bench cases were relatively small-scale disputes. Most of them never got anywhere close to trial, either because they settled, or because the plaintiff decided that the defendant was not financially worth pursuing, or because the defendant gave up.

In the year 1879 there were issued in the Divisions of the High Court in London - writs, 59,659. Of the actions thus commenced, there were settled without appearance, 15,732, ie 25.68 per cent; by judgment by default, 16,967, ie 28.34 per cent; by judgment under Order XIV, 4,251, ie 7.10 per cent; cases unaccounted for, and therefore presumably settled or abandoned, 20,804, ie 35.10 per cent. Decided in Court, 2,265, that is, 3.78 per cent of the actions brought. The Legal Procedure Committee of 1881 made some striking findings.

Until the Royal Courts of Justice opened in 1882, the Queen’s Bench Judges heard City of London commercial cases at the Guildhall. Its Courts were the centre of J.C.Mathew’s professional life.

The core conclusion of the Committee's Report was that these facts made it wasteful and inefficient to have rules which had the effect of imposing the same complex and protracted procedure on every case. The Committee recommended a more flexible approach. There should be a summons for directions in each Queen's Bench action, at which a Master or Judge would make procedural orders tailored to the requirements of the individual case. This radical proposal foundered on the opposition of practitioners and Judges. Solicitors resented the prospect of losing their traditional control over the pace of the litigation, while Judges did not welcome the prospect of having to manage cases individually. The summons for directions was introduced into the Rules of Court in 1883. It was voluntary, however, at the option of the parties, and this effectively neutralised it: before 1895, the summons for directions was hardly ever used. But Mathew never forgot the recommendations of the Legal Procedure Committee. He would make early case management, which was the core idea behind the summons for directions, the foundation-stone of Commercial Court procedure.

By the time the Legal Procedure Committee's Report was published, in October 1881, Mathew was a Judge. He was appointed in circumstances which saw the belated end of a long era in the legal history of England & Wales. The Judicature Acts of 1873 and 1875 had swept a myriad of pre-existing royal Courts of first instance up into a newly-minted and single High Court of Justice. But Parliament had held back from sweeping away all vestiges of the three ancient common law Courts of Common Pleas, Queen's (or King's) Bench, and Exchequer of Pleas. The consideration which had stayed its hand was that each of these Courts had its own president (a Chief Justice apiece for the Common Pleas and the Queen's Bench, and a Chief Baron in the Exchequer), and an outright merger would necessarily have meant demotion for two of them. So, for the preservation of judicial dignity, the common law side of the new High Court was originally split into three divisions, corresponding to the old Courts. But this was always intended as an interim expedient, to be phased out when the number of presidents was reduced to one by death or retirement. The reduction came to pass in late 1880, when Chief Justice Cockburn of the Queen's Bench and Chief Baron Kelly died within a couple of months of one another. (This may have been natural selection in action, but it was not a case of survival of the fittest: the third president, Chief Justice Coleridge of the Common Pleas, was the least dynamic and effectual of the trio.) The three common law divisions were combined into an enlarged Queen's Bench, and the names of the Common Pleas and Exchequer of Pleas were consigned to history after more than six centuries.

A fairly youthful-looking. Mathew. The image is undated, but is presumably from the early years of his judicial career.

Without Cockburn and Kelly, the new version of the Queen's Bench was two Judges short, and Mathew was one of the two men named to fill the vacancies in March 1881. (The other was Sir Henry Mather Jackson, QC and baronet. Although a QC, Jackson was a less prominent practitioner than Mathew, but he had the advantage of being an MP, which was a relatively common route to the Bench in the 19th Century. Jackson died within a week of the official announcement of his elevation, before he was sworn in.) Mathew's appointment was eye-catching for his religion and for the fact that he was not a QC. He was only the third Catholic Judge since the overthrow of the Stuarts. It was by no means unprecedented for a junior barrister to become a High Court Judge. But, in virtually all recent instances, the appointee had been Junior Counsel to the Treasury, and a Judgeship had been conferred as a reward for years of handling government cases. Mathew had never been "Treasury Devil" (although, whether he knew it or not, he had come close in 1879; but the job went to Archibald Levin Smith). This meant that the most recent parallels to his appointment were Colin Blackburn in 1859 and his own former pupil-master, Willes, in 1855. Since these had been two of the most outstanding common law Judges of the second half of the 19th Century, the omens seemed good.

But Mathew's beginnings on the Bench, like his start at the Bar, proved disappointing. This was partly a matter of experience (or inexperience). The Queen's Bench had an extremely varied general common law workload, which was a challenge for someone who had been a specialist at the Bar. (In his first year as a Judge, Mathew heard reported cases about landlord and tenant, local elections, personal injuries, and burial and cremation, but none of the shipping and insurance actions which had dominated his career as a practitioner). In particular, much of the professional life of a Queen's Bench Judge was spent on Circuit, trying mainly criminal cases. Mathew had been a member of the prosecution team during the criminal phase of the famous Tichborne Claimant litigation of the 1870's. But this had been a rare departure from the usual run of his commercial practice, and his overall experience of criminal work was negligible. Coming to criminal litigation after years of commercial cases, Mathew tended to adopt an approach which no doubt seemed to him to be suitably brisk and business-like, but which struck criminal practitioners - and, presumably, defendants - as unseemly and rushed. In civil cases, where Mathew should have been more sure-footed, he was persistently impatient with counsel or solicitors who did not proceed at the pace which he thought appropriate. Unnecessary procedural delay and cost always irritated him, and he tended to vent his frustration with sarcastic remarks aimed at practitioners. These may often have been intended humorously, but they invariably came across as merely offensive. The legal press noted the personality contrast between Mathew and Bowen. Bowen shared Mathew's contempt for procedural technicalities and his determination to get directly to the real issue in every case. But Bowen had the knack of making his point with a good-natured wit which was effective without causing resentment. Mathew, on the other hand, "had the scathing sarcasm of Juvenal, which wounds the vanity and hurts the wound". If, as The 'Times' suggested, Mathew "sometimes wounded when he meant only to amuse", that was little consolation to his victims. Mathew was also perfectly willing and able to be deliberately rude at times. Even when he was in good humour, pleasantries did not come easily to him. A law student who spent six weeks in close company with Mathew on Circuit as his marshal (a judicial assistant/secretary) remembered him struggling to find something complimentary to say when they went their separate ways: the best he could come up with was that the marshal had managed not to spill food and drink on the carpet in the Judges' lodgings. Mathew quickly acquired a reputation as an unpopular Judge.

Mathew (left) in 1883, by when he had been a Judge for two years and made himself thoroughly unpopular. The contrast with Vanity Fair’s portrait of James Bowen (right), which captures Bowen’s fundamental good-nature, highlights the different characters of these two friends and judicial colleagues.

However, Mathew was conscientious, willing to learn and clever enough to do so, and immensely hard-working (he was known to complain to the Queen's Bench clerks that they were not giving him enough to do). Just as at the Bar, he ultimately turned early failure into emphatic success. By the early 1890's, he was regarded as one of the very best trial Judges on the Bench, in criminal cases as much as in civil. By contrast with the perceived harshness of some of his colleagues, such as Sir Henry "Hanging" Hawkins and Sir John "Judgment" Day, there was a stroke of leniency in Mathew's conduct of criminal cases. He was deeply upset when he first passed sentence of death, and, at a time when there was no Court of Criminal Appeal (that was not established until 1907) the risks of wrongful conviction troubled him profoundly. In his address to the Lord Mayor in 1897, he spoke of the importance of criminal Judges safeguarding the rights of the accused to prevent the conviction of the innocent. The 'Times' thought that "perhaps it might sometimes have been thought that, in his anxiety to protect the accused, he would rather have sentenced the policeman than the prisoner". Mathew never entirely suppressed his instinct to go on the attack if he thought that a case was proceeding too slowly. As late as his promotion to the Court of Appeal in 1901, The 'Solicitors' Journal' qualified its approval with the warning that "his rapid insight, quick temper, and pungent humour are apt to show impatience". But he got better at controlling his temper, and generally managed to avoid outright rudeness.

Unsurprisingly, Mathew had no rival as a trial Judge in commercial cases. But opportunities for him to demonstrate his particular expertise became increasingly infrequent during the 1880's and early 1890's. Under the aimless leadership of Lord Chief Justice Coleridge, problems of delay and expense which had set into the Queen's Bench after the Judicature Acts only became worse. They were compounded by a shambolic administrative system, in which cases were taken out of the lists without notice, and parties, their lawyers, and witnesses seldom knew when a case would start until the very last minute. Most litigants had no choice but to put up with all this if they wanted their disputes resolved. But for the business world, arbitration was a readily available and increasingly attractive alternative. It was widely believed in the 1880's that a large number of cases which would once have been litigated in the Queen's Bench now went to arbitration instead. Commercial litigation was certainly in decline. To the national and legal press, a substantial part of the legal profession, and some Judges, including Mathew and Bowen, the reluctance of commercial litigants to use the Courts was embarrassing. From the late 1880's, the idea of a specialist Commercial Court, or at least of arrangements for assigning commercial cases to Judges with experience of commercial litigation, became increasingly popular. But Lord Coleridge took the view that if people did not want to use the Courts, that was a matter for them. He did not believe that the judiciary had any particular responsibility to improve the offering of the Queen's Bench, and he had a psychological aversion to more or less any sort of reform.

Although Lord Coleridge was a weak leader of the Queen’s Bench Division as Lord Chief Justice, he was firm in his opposition to reform in general, and to the creation of a Commercial Court in particular.

Mathew's vastly-improved judicial reputation was no doubt one strong reason why the incoming Liberal government asked him in 1892 to preside over the Evicted Tenants Commission. The Commission's remit was to consider whether there was justification for tenants' claims to be restored to the land or compensated and, if so, how those claims should be processed. The "War" had been characterised by rent-strikes on the part of the tenants and evictions by the landlords. The Commission's remit was to investigate tenants' claims to be restored to the land or compensated. The government may have hoped that the unusual way in which Mathew combined an Irish Catholic background with membership of the English establishment would make him acceptable to both parties. But, in the bitter atmosphere of late 19th Century Anglo-Irish politics, Mathew was accepting the most poisonous of chalices. It is virtually impossible to see how any realistic outcome could have satisfied both sides. Even before proceedings had opened, the landlords, sensitive to Mathew's Home Rule sentiments, were muttering darkly that it was a foregone conclusion that the Commission would favour the tenants. The Commission was going to have to exercise delicate diplomacy to prevent its proceedings from becoming merely another front in the “War”. The impatient Mathew, with his interventionist manner of conducting hearings and his hair-trigger temper, was not blessed with the ideal personality for the challenge.

Mr Carson QC: I say the whole thing is a farce and a sham. I willingly withdraw from it. I will not prostitute my position by remaining longer as an advocate before an English Judge.

Mathew and Edward Carson did not really hit it off at the Evicted Tenants Commission. They got on much better in later years.

The first day of sittings, in Dublin on 7th December 1892, was a public relations disaster. Mathew engaged in a blazing row with Edward Carson MP, QC, about the cross-examination of witnesses. Carson, Unionist politician and ambitious, often brilliant, but sometimes melodramatic barrister, insisted that, as counsel for one of the leading landlords, he was entitled to cross-examine witnesses from the tenants' side. Mathew, emphasising that the Commission was not sitting as a Court of law and determined to get through the witness evidence at a brisk pace, ruled that all questions should be submitted in writing and would be put to witnesses by the Commissioners. As the debate descended into an acrimonious slanging-match, Mathew reprimanded Carson for lack of professionalism. Carson responded by storming out. The landlords refused to participate any further, and two of Mathew's fellow-Commissioners resigned.

Mathew suspected that the landlords had never seriously intended to participate in the hearings, and that they had been looking for an excuse to stage a walk-out. He may well have been right. But if he was, his confrontational manner gave the landlords the very excuse which they wanted. Elements of the national press endorsed Carson's denunciation of the proceedings as "a farce and a sham". Mathew found his conduct compared in print with the legendary tyrannies of James II's Judges. Even more damagingly, he was accused of brazen pro-Irish nationalist bias in Parliamentary speeches by Conservative and Unionist politicians, including the once and future Prime Minister Lord Salisbury and his deputy in the Commons, Arthur Balfour. The Master of the Rolls, Lord Esher, stoutly stood up for his junior colleague in a speech at the Lord Mayor's Banquet. The legal profession and press also defended Mathew's integrity and character.

But, even among lawyers, there was a widespread sense that Mathew's conduct had been ill-judged. More fundamentally, it was widely believed that he should never have allowed himself to be become involved in such a political affair in the first place, and that he should have declined the position on the Commission. The Commission’s final report, in February 1893, merely prolonged the controversy. Mathew and his remaining colleagues recommended that a Special Commission should be established to consider claims by individual tenants, with powers to restore them to their tenancies land and (in effect) to compel the landlords to sell the land. Unionists, perceiving this as a complete capitulation to the tenants, renewed their personal attacks on Mathew, and defeated an 1894 Bill which would have passed the Commission’s proposals into law. (The recommendation for a Special Commission was eventually adopted more than a decade later, in the Evicted Tenants (Ireland) Act 1907.)

The fallout from the Evicted Tenants Commission was almost certainly a setback to Mathew's career prospects. In an age when the judiciary was much smaller than today, vacancies for common law Judges in the Court of Appeal were relatively few and far between. An opening had arisen in July 1892, shortly before Mathew was appointed to the Commission. The Conservative government of the day overlooked Mathew in favour of Archibald Levin Smith, who was both younger than Mathew and his junior as a Judge. Perhaps Lord Salisbury was already suspicious of Mathew's Home Rule sympathies, although Smith's status as a former "Treasury Devil" may have given him an advantage. The next vacancy, in 1894, arose under the Liberals. A new Law Lord was needed, and filling this post was likely to leave a gap in the Court of Appeal. The Liberals might have been expected to feel a certain guilt about Mathew's ordeal on the Commission, which had after all been their idea. Sections of the legal press spoke confidently of Mathew as a candidate for the Court of Appeal. Mathew himself hoped that he might even get the position in the Lords. This was naive. As the more astute legal journals realised, if the Liberals promoted Mathew, they would inevitably be accused of blatantly rewarding him for service on the Commission, and the whole controversy would re-ignite. The Liberals instead filled the vacant judicial posts with their own people, as both political parties commonly did at the time. Former Liberal MP Sir Horace Davey was promoted from the Court of Appeal to the Lords, while Liberal Law Officer Sir John Rigby, who had been Attorney-General for only two months, replaced Davey. Davey had at least been an outstanding Chancery barrister. Rigby was a non-entity, and proved a complete failure as a Judge.

As the mid-1890's approached therefore, and as Mathew himself neared his mid-60's, he seemed destined to end his career as a first-instance Judge. This appeared to condemn him to see out his days in a Court which was now under almost constant attack for inefficiency, delay, incompetent administration, hopeless lack of leadership, and costly and wasteful procedures. The numerous problems besetting the Queen's Bench continued to get worse, while Lord Coleridge affected to be serenely unconcerned. Commercial litigation reached such a low ebb that The 'Solicitors' Journal' complained that "it may fairly be said that the greatest court of the greatest commercial empire is denuded of commercial business."

In late 1891, Mathew and Bowen had been instrumental in persuading Coleridge to convene a Council of Judges to consider possible reforms. They were also closely involved in the drafting of the 101 Resolutions which the Council debated over three days in June 1892. Resolutions 32 to 38 proposed that Queen's Bench commercial cases would be assigned to a special list, which would be dealt with by two specialist Judges. This was an idea which had been discussed since the late 1880's. The Council endorsed the proposal by twenty votes to five. Coleridge was one of the five. Since the Lord Chief Justice was the President of the Queen's Bench Division, his opposition had the practical effect of a veto. Coleridge was unswervingly attached to judicial tradition and old ways of doing things. His father had been a Judge of the ancient common law Court of Common Pleas, and Coleridge himself had started his judicial career in the Common Pleas in 1873. He had never really got over the shock of the Judicature Acts, which had abolished all of the old Courts, with their ancient heritage and separate traditions, and replaced them with a single High Court. Coleridge was constitutionally opposed to further reform in general. Specifically, he detested the idea that particular types of work should be directed towards particular Judges. In Coleridge's mind, any form of judicial specialisation carried with it the unacceptable implication that some Judges were more capable than others.

Commercial Court

32. There shall be a cause list for London headed “the Commercial List. 33. In this list, none but commercial causes shall be entered.

From the Judges Resolutions of 1892.

Mathew looking relatively relaxed in 1891. His judicial reputation was soaring, but he was about to take a very public battering in the Evicted Tenants Commission.

Energetic where Lord Coleridge had been apathetic, Lord Chief Justice Russell simply ignored remaining resistance to a Commercial Court.

Mathew's prospects changed for the better in 1894. In March, the Liberals returned - briefly - to office. In June, Lord Coleridge died. Mathew had generally been on friendly terms with Coleridge, but their characters had been very different. Mathew, a plain-speaking Irish extrovert, was energetic and driven, witty and sarcastic, intolerant of old technicalities and itching to reform civil procedure, and his politics were towards the radical end of the contemporary scale. The dignified and refined Coleridge, very much the reserved English gentleman, was introverted by comparison, and conservative in all things, notwithstanding that he had once been a Liberal politician. He worshipped old traditions, recoiled from reform, and had none of Mathew's dynamism. Coleridge's successor was not only a good friend of Mathew, but much more in sympathy with him by background and temperament. Like Mathew, Charles Arthur Russell was an Irish Catholic of Liberal and Home Rule persuasion, who had moved to England to make his name and fortune at the Bar. Like Mathew, although not to the same extent, he had practiced commercial law. Unlike Mathew, he had become one of the most outstanding advocates of his generation, and had participated actively in politics. Russell had been a Liberal MP for fourteen years, and twice Attorney-General. It was through his political links that Russell came to succeed Coleridge under the Liberal government. Russell shared with Mathew an energetic capacity for hard work and a sometimes volatile temper. More importantly, he firmly supported the creation of a Commercial Court.

Soon after taking office, Russell asked the Rules Committee to draft amendments to the Rules of Court to make special provision for commercial cases. When the Committee dragged its feet, Russell reverted to the old idea of allocating commercial cases to a special list with a dedicated and specialist Judge. Since this change was purely administrative in form, it could be made without amending any Rules. In early 1895, the Queen's Bench Judges endorsed the Notice as to Commercial Causes and chose Mathew as the first Commercial Judge. The legal press approved the nomination as "manifestly the best selection which could be made". Mathew heard the first Commercial Summonses in Room 99 at the Royal Courts of Justice on Friday 1st March 1895. There were 32 applications, mostly for transfer into the Commercial List and for directions. Mathew disposed of them in a morning. The following Friday, he tried the first Commercial Court case, Burney v Elliman.

Neither Burney nor Elliman are in business today. But the parties to the first Commercial Court case hold a secure a place in legal history.

The Commercial Court was the culmination of J.C. Mathew's career, his enduring achievement and his own legal monument. Mathew approached his new role with the benefit of a career's worth of experience of commercial litigation, and with a deep reservoir of frustration at the way in which commercial cases had been mishandled for decades in the Queen's Bench. He had a fund of ideas for eliminating delay, inefficiency and waste, and an energy to put them immediately into practice. In the hands of a less capable, less determined, and less imaginative Judge, the new initiative might easily have come to nothing. Elements of the legal press speculated that the loss of commercial work from the Queen's Bench had gone too far to be reversed. Even those who believed that the decline could be stopped sometimes thought that something more radical than the Notice, which had virtually no legal status, was needed. But, armed with nothing more than the Notice and his own initiative, without any formal backing in the Rules or in statute, Mathew virtually single-handedly established the Commercial Court as the world's leading forum for the resolution of commercial disputes.

It is ordered:

That the action be transferred to the Commercial List.

That points of claim be delivered by the plaintiff in seven days.

That points of defence be delivered by the defendant in seven days.

That list of documents be exchanged between the parties in seven days and inspection be given in three days afterwards.

That the action be tried without a jury.

That the date of the trial is fixed for -

That the costs of this application be costs in the case.

A typical order on the summons for directions in Mathew’s Court. The pace was brisk, and unnecessary procedures were omitted.

He did it by actively engaging with every case at the earliest opportunity. It was the philosophy which had informed his career in commercial work: find out what the case was really about, and focus on that. The Notice was deliberately drafted to ensure that anyone who wanted to litigate in the Commercial Court had to take out a summons at an early stage, to apply for transfer into the Court. This brought the case in front Mathew, who used the hearing as an opportunity to make orders for the management of the whole case. In effect, Mathew treated the application to transfer as a summons for directions. In this way, Mathew and Bowen's 1881 plan to make the summons for directions compulsory became real, at least in commercial cases. This early hearing was the mechanism by which Mathew got a grip on each case, and eliminated the procedural drift which typically characterised Queen's Bench litigation. At the hearing, he interrogated counsel or solicitors about what the real issues were and what orders were appropriate. The lazy ways of following the same routine in every case, regardless of its nature, did not apply in Mathew’s Court. Mathew took it as read that, by the time the Writ was issued in a commercial dispute, the parties and their lawyers already knew what the case was really about. This meant that pleadings, particulars, disclosure, and interrogatories were not usually needed to help knock a commercial case into shape. In practice, they often tended to serve as distractions. Mathew believed that the best way to maintain focus on the real point of a case was to make the simplest possible procedural orders at the earliest possible stage, and then get the action to trial at the soonest possible date.

Determined to minimise delay and cost, Mathew constantly sought to streamline procedure. With limited formal tools at his disposal, he proceeded informally. Parties were persuaded - or browbeaten - to do without pleadings, dispense with the strict rules of evidence, and agree facts. If Mathew identified a point of law which might dispose of a case without a full trial, he would generally order it to be determined as a preliminary issue, without pleadings or evidence. If pleadings were necessary, he ordered that they take the form of brief "Points" of Claim or Defence. The samples in ‘The Practice of the Commercial Court’ (1902) give an indication of what Mathew expected: no pleading is more than a page long. To make quite sure that pleadings did not get out of hand, Mathew set timetables which were unimaginably short by modern standards. Formal - and expensive - affidavits of documents sworn by the parties were replaced by lists of documents prepared by their solicitors. Commercial Court practitioners soon learned that it was a waste of time applying for further and better particulars or interrogatories: Mathew would not order them unless, exceptionally, there was a genuine need. Under the strict rules of evidence, all facts normally had to be proved by a witness: mere documents were inadmissible hearsay, unless a witness gave evidence to verify them. But parties could agree to dispense with the strict rules. Mathew routinely persuaded parties of the good sense of agreeing to treat documents as evidence of the truth of their contents. As a result, the taking of evidence abroad on commission, which had previously been a slow and expensive stage of any commercial case which involved events overseas, was almost unknown in the Commercial Court.

Mathew in around 1895, the first year of the Commercial Court.

Mathew also found a way to avoid the usual disarray of the Queen's Bench listing system, in which every case went into a list with a collection of others and was heard whenever the Judge got round to it. He fixed the trial date at the hearing of the application to transfer. The innovation sounds simple, but it was revolutionary by Queen's Bench standards. It proved one of the single main incentives for parties to use the Commercial Court.

Mathew adopted at trial the same robust approach as at interlocutory stages. A trial in his Court was typically completed within a day, and he more often than not gave judgment the next day. Like everything else to do with the Commercial Court, a Mathew judgment was brisk and to the point, with no ostentation or ornament. It would usually fit within two or three pages of the law reports. Unlike Bowen, whose judicial turn of phrase was much admired, Mathew was no stylist. His prose was terse and workmanlike. But it had the great merit of clarity. Mathew wrote for the benefit of the parties who were paying for the case, not for legal commentators or posterity. Since the parties knew what the case was about, he saw no need to narrate the background in tedious detail: a short summary of his findings of fact was sufficient. Similarly when it came to the law: his judgments usually contained little more than a short statement of the relevant principles as he understood them. He was not a great one for citation of authority, still less for discursive analysis. He believed that litigants wanted a clear decision, not a discussion, and one of his great strengths as a Judge was "remarkable power of rapid decision". Mathew seldom had any difficulty in making up his mind. But a quick and clear decision is of little value if it is arbitrary, ill-thought out, or plainly wrong. Another of Mathew's great judicial strengths was that his judgment was very good. His thorough understanding of commercial law and practices was reinforced by a powerful practical intelligence. Mathew's decisions were almost invariably in accordance with what the business-world could recognise as commercial common sense. Even though his judgments were never detailed expositions of the law, Mathew's record of being upheld in cases which went to the Court of Appeal was impressive.

I am clearly of opinion that this was not a charterparty for a lump sum freight. Mr Boyd says that the charter described the utmost capacity of the ship, and this meaning he seeks to derive from the words “guaranteed by owners to carry 2600 tons deadweight”. But this is an extraordinary interpretation to put on the words. They mean that the ship shall be capable of carrying 2600 tons at least. Mr Boyd further contended that the words “full and complete cargo” meant 2600 tons. But there is nothing in the charterparty to justify that view. He also suggested that in the sentence “all per ton deadweight capacity as above” the words “as above” referred to 2600 tons. But if that was meant it is singular that the charterparty does not say so in terms. The deadweight capacity of the ship exceeded 2600 tons, and the charterers must pay as for her deadweight capacity to carry a “full and complete cargo”. Mathew’s judgments were refreshingly brief. This one is admittedly extreme, but it is not unique: Steamship Heathfield Co Ltd v Rodenacher (1895-1896) 1 Reports of Commercial Cases 448 (162 words).

By his concentration on efficiency and economy, combined with his knowledge of commercial law and his great common sense, Mathew quickly convinced commercial litigants and their lawyers that he could dispose of cases at least as quickly and cheaply as any arbitrator. The Commercial Court was an instant success. After a year's operation, 398 cases had been transferred into the Court. 158 of them had been tried, and 90 had settled, often in response to judicial suggestions at the summons for transfer. 158 trials was close to 10% of the Queen's Bench trials in London during the period. But it was hard work, and Mathew did most of it. Apart from short periods when he went Circuit and was replaced by Lord Russell, Mathew sat continuously in the Commercial Court in its first year. This had always been the plan. The Queen's Bench Judges realised that the experiment would work best if a case was dealt with by the same Judge at both the directions stage and at the trial. This meant leaving the same Judge in charge for as long as practical, and the idea had been that this would be one year. But when the legal profession learned in early 1896 that Mathew was to be replaced by either Collins J or Kennedy J, it reacted with dismay. Although, in theory, any other Judge could adopt Mathew's practices, it was obvious that Mathew himself was the principal reason for the Court's success. Practitioners warned against replacing him before the Court had firmly established its place in the judicial system, and the Law Society submitted formal representations that Mathew must stay. A meeting of the Queen's Bench Judges in May 1896 decided to leave well alone. Mathew continued to run the Court almost single-handed, subject to occasional short periods when Russell or Collins stood in, until late 1897, when leading commercial specialist John Bigham QC was appointed to the Queen's Bench. After that, Mathew, Kennedy, and Bigham took it in turns to sit as Commercial Judge.

Earlier in 1897, the first Commercial Judge had participated in another piece of legal history. In Allen v Flood [1898] AC 1, the defendants were the union representatives of a group of ironworkers who were retained by a shipyard on a day-to-day basis. They told the shipyard that the ironworkers would not work if the yard employed the claimants, who were shipwrights. The great issue in the case was whether the defendants had committed any tort against the plaintiffs. The legal argument turned on the point that, since the ironworkers had no continuing contracts of employment, they were entitled not to turn up for work. The trial Judge, Mathew's colleague Kennedy, told a jury that the threatened withdrawal of labour could nevertheless amount to a tort if the defendants had acted maliciously. The Court of Appeal agreed. The issues were legal, but the case was politically charged. When the appeal to the House of Lords was argued in December 1895 before a seven-strong panel of former Lords Chancellor and mostly political appointees, opinions were sharply divided. Indications were, however, that a majority favoured allowing the appeal. Lord Chancellor Halsbury, who was determined to uphold Kennedy's decision, unleashed a cunning plan. In April 1897, the appeal was argued all over again, this time before nine Lords and eight Queen's Bench Judges. It was the first time since the Judicature Acts that the Law Lords had exercised their ancient right to summon the Judges to advise them. It was the last time that they would ever do so. Six Judges advised that Kennedy had been right. Only Mathew and Robert Samuel Wright made the principled point that the ironworkers had a legal right not to work, and the exercise of a legal right could not be a tort. Halsbury's hopes that the weight of judicial opinion would persuade his colleagues were in vain: the appeal was allowed by six to three.

Mathew's achievement in the Commercial Court was a personal triumph. Whether it would revive his prospects of promotion looked more doubtful. The Conservatives returned to government in June 1895, and Lord Salisbury was still given to grumbling that Mathew had disgraced his office in 1882. In 1897, Lord Esher retired after fifteen years as Master of the Rolls. When Lord Justice Lindley replaced him, it was Collins, eleven years younger than Mathew and ten years his junior in the Queen's Bench, who filled the vacancy in the Court of Appeal. When Lord Justice Lopes retired soon afterwards, Roland Vaughan Williams, another younger man who had only been a Queen's Bench Judge for seven years, took his place.

These precedents meant that Mathew's chances did not look promising when the sudden illness and retirement of Archibald Levin Smith, Master of the Rolls, created a common law vacancy in the Court of Appeal. Remarkably however, Lord Chancellor Halsbury, who had a terrible reputation for basing his recommendations for judicial posts on political or personal grounds, proposed Mathew. Halsbury suggested Joseph Walton QC, the most successful Commercial Court practitioner at the Bar, to replace Mathew in the Queen's Bench. Prime Minister Salisbury prevaricated, and muttered about placing Walton in the Court of Appeal and leaving Mathew where he was. But Halsbury got his way. On 19th October 1901, more than twenty years after his appointment as a Judge, J.C. Mathew became a Lord Justice of the Court of Appeal. (1901 was a memorable year for Mathew: he had already become Treasurer of Lincoln's Inn.) The 'Solicitors' Journal', welcoming the "all too tardy recognition of the most brilliant ability in the King's Bench Division", predicted that Mathew would be "a tower of strength" in the Court of Appeal. The 'Times' could not resist reminding readers about the Evicted Tenants' Commission, and emphasised that Mathew was a Catholic of Gladstonian Liberal persuasions. But it conceded that he had had "a brilliant career" at Trinity College, and that he was "a very able commercial lawyer".

The only question on which I doubted was whether it would not be better to make Walton Lord Justice at once over Mathew’s head. Mathew certainly behaved abominably in that Irish case. Prime Minister Lord Salisbury to Lord Chancellor Halsbury, September 1901.

Many people were hugely impressed by Mathew’s achievement in the Commercial Court. Lord Salisbury was not one of them.

The Court of Appeal should have been the summit of Mathew's career. It was an anti-climax. Aged seventy-one in 1901, Mathew was one of the oldest High Court Judges. He had also been one of the hardest-working for nearly two decades. One of the reservations about him when he had been considered as Junior Counsel to the Treasury in 1879 had been that his health was thought to be delicate. In fact, he had withstood his relentless judicial workload, including stints helping to clear backlogs in the Chancery and more than two years running the Commercial Court, remarkably well. (Poignantly, it was A.L. Smith, who had been appointed "Treasury Devil" in preference to Mathew, who suffered physical and mental collapse and a premature death.) But Mathew had become more susceptible to illness towards the turn of the Century. The official portrait photograph of the newly-appointed Lord Justice Mathew, now on display in the Rolls Building, captured a face which was still forceful and determined, but which also looked rather tired.

The official portrait of Lord Justice Mathew following his promotion to the Court of Appeal aged seventy-one, after twenty years on the Bench.

Moreover, although Mathew had turned himself into a brilliant trial Judge, he was less obviously in his element in an appellate Court. One of the principal functions of the Court of Appeal was to develop the common law by resolving unanswered points and moulding existing principles to new situations. This speculative side of legal practice had never been Mathew's strongest point. Undoubtedly, his knowledge of the law, particularly commercial law, was profound. But his focus was firmly practical rather than academic, rooted in the facts of particular cases rather than in legal abstractions. Compounding matters, much of the Court of Appeal’s work at the beginning of the 19th Century involved appeals under the Workmens' Compensation Act 1897. Nearly a quarter of Mathew's reported appeals were workers' compensation cases. It was an area with which Mathew had no connection. The statute was dry and complex. Its passage into law had been politically controversial, but there was little in it to interest a commercial lawyer. During his time in the Court of Appeal, often dealing with dull Compensation Act cases, Mathew generally maintained his first-instance habit of delivering short judgments which stated his basic conclusions without detailed elaboration. It was not the stuff of which landmarks in the law were made, and Mathew made little impact.

Indeed, he left little impression on the letter of English law at any stage of his career. It is rare for a Mathew judgment to be cited today: possibly, from time to time, Chippendale v Holt (1895-96) 1 Com Cas 197, on "follow settlements" clauses in reinsurance policies; Asfar v Blundell [1895] 2 QB 196, on when goods are legally lost even though they retain some physical existence; or Tyser v The Shipowner's Syndicate [1896] 1 QB 135, on the several nature of the liability of Lloyd's underwriters. The two best-known cases from Mathew's time in the Court of Appeal both marked wrong turns in the law. Chandler v Webster [1904] 1 KB 493, one of the "Coronation Cases" arising out of the cancelled coronation of Edward VII in 1902, was significant in the development of the doctrine of frustration, but the Court's conclusion that losses lay where they fell following frustration was overruled by the House of Lords in Fibrosa v Fairbairn [1943] AC 42. The infamously obscure Braithwaite v Foreign Hardwood [1905] 2 KB 543 left generations of lawyers baffled as to whether the Court of Appeal had decided, contrary to all orthodoxy, that a defendant's repudiation of a contract released the plaintiff from further performance even if the plaintiff did not accept the repudiation. However, Mathew's reputation emerged unscathed when the House of Lords rejected that interpretation of the case in The 'Simona' [1989] 1 AC 788: the Lords said that Mathew's analysis was orthodox and correct, and that the Braithwaite heresy was all the fault of the two other Judges.

Such occasional instances aside, there is little to interest the legal scholar in Mathew's body of work. If anything of his is mentioned today, it is usually his joke that the Courts, like the Ritz Hotel (or, in some accounts, the Savoy), are open to everyone. This sarcastic jibe about the cost of litigation is in keeping with Mathew's intolerance of unnecessary cost. But the attribution appears to be apocryphal: Mathew's obituarists do not mention it among his witticisms, and it seems to be first recorded in Robert Megarry's 'Miscellany-at-Law', published nearly fifty years after Mathew's death.

Mathew's reputation as an after-dinner speaker reflects the sociable side of his nature. The diary columns of the law journals regularly reported his attendance, often as the key entertainment, at functions hosted by legal societies or City of London guilds and livery companies. Aside from the Hardwicke Society and Lincolns' Inn, the clubbable Judge was a member of both the Athenaeum and the Reform. It was at the Athenaeum that Mathew suffered a severe stroke on 6th December 1905. For a few weeks, it was thought that he might recover and return to duty. But by early 1906, it was clear that such hopes were forlorn. Mathew resigned on 26th January 1906, and was awarded a pension of £3,500 per year. His judicial career ended a few weeks short of a quarter of a century after it had begun. For some time, his life seemed likely to end too. But Mathew survived, and, though he was left physically impaired, his mind largely recovered: he enjoyed listening to the talk of visitors at home, and could generally join in conversation, although he sometimes lost track of his words.

The Hall of the Atheneaum Club: J.C. Mathew on the far left.

J.C. Mathew was married on Boxing Day 1861 (or St Stephen's Day, to someone of his Irish background) to Elizabeth Biron. Elizabeth was the sister of Robert Biron, who shared chambers with Mathew at Dr Johnson's Buildings, in the Temple. Her father was the Vicar of Lympne, in Kent, and the marriage was conducted at his Church. The couple lived for a time in Richmond, before moving to Cornwall Gardens in Kensington. They eventually settled in Queen's Gate Gardens, a few hundred yards closer to the Kensington Museums. The location was conveniently close to the Brompton Oratory, where the family worshiped.

James Charles and Elizabeth were parents to three daughters and two sons: Elizabeth, born in 1865; Theobald (1866); Mary (1867); Charles James (1872); and Katharine Mary (1874). (A third son, James, who was their last child, died in infancy.) From the age of fourteen, Elizabeth kept a diary, which was published in edited form in 2019 as 'The Diary of Elizabeth Dillon'. It records a happy home life in a loving, devoutly Catholic, and highly-cultured family (Elizabeth herself spoke French, German, and Italian, and took literature classes at King's College London). The close-knit family took regular theatre and gallery outings, made trips to Europe, and holidayed regularly in Ireland and at Folkestone. As she grew up, Elizabeth became engaged in Irish politics. She shared her father's Home Rule views, and, in time, became involved in more radical Irish nationalism. She was enthralled by the prominent nationalist politician John Dillon. They were married in 1895 and had six children. Elizabeth's second family life was as happy as the first, but much shorter: she died in 1907, aged forty-two, after a catastrophic seventh childbirth.

Mary Mathew devoted herself to her faith by becoming a Carmelite nun: her decision to live a cloistered life which virtually cut her off from her family greatly distressed her parents and her siblings. Mary suffered severely from asthma from childhood, and died from lung complications in 1897. Little seems to be recorded about Katharine Mary, who died in 1937.

Born and brought up in London, Elizabeth Dillon became a committed Irish nationalist. She died in 1907, the year before her father.

Both sons became barristers. Theo, named after "Father Mathew", was called to the Bar in 1890. He was a pupil of commercial barrister Joseph Walton, who became the most prominent practitioner of the Commercial Court's first five years. This gave Theo a grounding in commercial law, and he practised for some years in the Court which his father had established. He sometimes even appeared before Mathew J, although he seems always to have had a leader on these occasions. Theo was also the first editor of The 'Times Reports of Commercial Cases', which were launched in 1895 specifically to report Commercial Court decisions. In 1902, he published 'The Practice of the Commercial Court', a practical guide to the streamlined procedures which his father had developed. But Theo drifted away from commercial work in the first decade of the twentieth century, and eventually settled down as a defamation specialist. Like his father, he remained a junior counsel throughout his career. He had a large number of pupils. Two of them, Quintin Hogg and Kenneth Diplock, achieved far greater legal eminence than Theo himself. A third, Clement Atlee, was Deputy Prime Minister in the Second World War and Prime Minister from 1945-1951. Theo achieved minor judicial office as Recorder of Margate and later of Maidstone. But even during his lifetime he was better known as a humourist than as legal figure: his 'Forensic Fables' remain in print. Theo died in 1939, just as he was about to follow his father in becoming Treasurer of Lincoln's Inn.

Unlike his father and elder brother, Charles James Mathew did become leading counsel. However, his appointment as King's Counsel in 1913 may have had more to do with his status as an MP than with any great legal ability: MP's were customarily given the title on request. But Charles James did establish a respectable Chancery practice, with a trade union side to it. He died suddenly after an operation in 1923. His elder son, another Theobald, was called to the Bar, but transferred to the solicitors' side of the profession after only a few years. Sir Theobald, as he became, was a highly-respected Director of Public Prosecutions from 1944 until his death in 1964. He had served his articles as a solicitor in the firm of Charles Russell. In 1923, he married Phyllis Helen Russell, the daughter of the firm's senior partner. Phyllis was also the granddaughter of Lord Russell of Killowen, who had collaborated with her husband's grandfather in the creation of the Commercial Court and been one of its first Judges. A fourth generation of the Mathew family took to the law when Theobald and Phyllis's son, John Charles, became a barrister. Although he was descended from Commercial Judges on both sides, he followed his father into the criminal side. John Charles Mathew QC was a senior prosecutor at the Old Bailey and became one of the leading criminal barristers of his generation. He died in January 2020, a short time before the 125th Anniversary of his great-grandfather's Court.

Aside from his family and his enjoyment of convivial company, James Charles Mathew's interests away from the law and the Courts were cultural. He was both a music-lover (The 'Law Journal' thought that "the London concert-rooms had few more regular attendants") and widely-read. Indeed, Mathew had a cultural and intellectual open-mindedness which influenced his professional work, and he was noted for his knowledge of the commercial laws of Europe and the USA. The fact that he wrote the 'Dictionary of National Biography' entry on William Müller, a Bristolian landscape painter of Prussian descent, suggests an informed interest in the visual arts. Mathew also contributed the entries for his uncle, "Father Mathew", and his friend and colleague, Charles Arthur Russell. The 'Law Times' thought that Mathew generally captured the character of the late Lord Chief Justice very successfully, but questioned his judgment in "including patience among Lord Russell's judicial virtues". Mathew never really managed to master patience in his professional life either, much though his judicial temperament improved after his bad start. But it was universally agreed that he was fundamentally benign, a lively, cultured, and witty personality, who was stimulating and entertaining company, considerate and loyal to his many friends.

The Medway at Gillingham, by W.J. Müller. The Mathew family regularly holidayed at Folkestone, not very far around the Kent Coast.

Mathew's often compassionate approach to criminal cases reflected a basic kindness, and, unlike many busy practitioners before and after him, he was generous in the time and attention which he gave to his many pupils. He took an interest in legal education, and was a member of the Bar's Council of Legal Education for many years. He remained firm in his Roman Catholic faith to the end of his life.

The Right Honourable Sir James Charles Mathew died at home early on 9th November 1908. It was Lord Mayor's Day. In his address that morning to the new Lord Mayor on his customary visit to the Law Courts, Lord Chief Justice Alverstone paid tribute to "one whose name has name has so long and honourably been connected with the discharge of official business affecting the commerce of the City of London". At the Mansion House Banquet the same evening, Alverstone told an audience of dignitaries which included Prime Minister Asquith, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Bishop of London, and Mr & Mrs Winston Churchill, that Mathew had been "a great commercial lawyer, who was as well known and respected at the Bar and on the Bench by the citizens of London as any Judge has ever been".

J.C. Mathew, aged 30: a talented and ambitious barrister, recently married, still short of work, but on the threshold of success.

Reginald Bray was in charge of the Commercial Court that November. When he came into Court on the morning of the 10th, fellow Commercial Judges John Bigham and Joseph Walton joined him on the Bench as he paid tribute to the only true begetter of the Commercial Court. All three had appeared before Mathew in the Court's earliest days. T.E. Scrutton KC expressed the admiration of the Bar for "the great Judge they had lost". In the Admiralty Court, President Sir John Gorell Barnes, the most successful of Mathew's pupils, paid his own respects to "one of the greatest Judges the country has had." The legal press had already pronounced Mathew "the greatest commercial lawyer of his time" on his enforced retirement nearly three years before. It repeated such praise at his death. In twenty-seven years, Mathew had completed a journey from much-resented new Judge to revered legal giant, "one of the most illustrious of modern Judges". The 'Times', which had condemned Mathew in 1892 for running the Evicted Tenants Commission like a tyrant, now told its readers that "no more nimble mind... ever administered English law... there was a strain of genius in the man and all he did; there was a strain, rarer still, and unforgettable, of generosity and magnanimity in all his relations of life".

After a requiem mass at the Brompton Oratory, Mathew's coffin was taken by train and steamer to Cork. He was buried in St Joseph's Cemetery, which his uncle had established in the 1800’s, in a private vault beside his mother and father. Elizabeth, Lady Mathew, died in September 1933, aged ninety-six. She thereby surprised her friends, who had recently enjoyed her "brilliant intellect, conversation and insight", and had confidently expected to celebrate her hundredth birthday. Like her husband of forty-seven years, she was buried at Cork, presumably in the same vault.

It was no great distance from St Joseph's to Lehenagh House. Mathew had sold the building in 1882 (the family no longer visited often enough to justify the expense of upkeep, and the House was too small for them all anyway), and it has long-since been demolished. The more modern homes of North and South Avenue, The Drive, and The Gates stand on the site, and there do not appear to be any visible remains at ground level. But, viewed from the air, the surrounding roads still clearly mark out the boundaries of the grounds which once surrounded the first Commercial Judge's childhood home.