When Michael Robert Emmanuel Kerr became a Queen's Bench Judge, he set a number of eye-catching precedents: first Judge of England & Wales for a millennium not to have been born a subject of the Crown; first Commercial Court Judge to have featured as a character in a best-selling children's book; and first High Court Judge to have been interned during wartime as an enemy alien.

These trailblazing achievements were all the result of Kerr's family background. He was born in 1921 into a cultured and bohemian Berlin family. His mother, Julia, was a pianist and composer, who wrote an opera about a mermaid which was staged in Germany in the late 1920's. His father, Alfred (born Alfred Kempner), was a prominent writer and radio broadcaster, best-known as a drama critic, but with sidelines in several other areas, including forceful attacks on the Nazi party as it rose to powe

Nazi resentment of this aspect of Alfred's work was exacerbated by the fact that the Kerrs were Jewish, and Hitler's accession as Chancellor in 1933 placed them in imminent danger. The family took refuge in Switzerland, then France, and arrived in London in 1936. Michael's younger sister Judith, creator of Mog and the Tiger Who Came To Tea, wrote a (slightly) fictionalised account of their migration in 'When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit', in which Michael appeared as "Max".

In London, Alfred worked on film scripts, earning enough money, bolstered by financial support from family and friends and scholarships, to send Michael to Aldenham School. Intelligent and hard working, Kerr was a star pupil (he had been top of his class in France, notwithstanding that he had spoken barely a word of French when the family arrived in the country). On top of academic success, he developed an excellent game of tennis and played in goal for the school football and hockey First XIs. In 1939, he won a scholarship to Cambridge, and chose to study law at Clare College.

Now well-settled in Britain, the Kerrs applied for citizenship, but the process was still pending at the outbreak of the Second World War. In consequence, Kerr, returning to his Cambridge rooms one morning in May 1940 after a game of tennis, found himself arrested as an enemy alien, a victim of Churchill's philosophy that it was best to "collar the lot" and round up all German citizens in Britain, regardless of their apparent enthusiasm (or lack of it) for the Nazi regime.

Alfred Kerr making a radio broadcast, probably involving unflattering remarks about Hitler.

Still in his tennis clothes, Kerr was shipped off to internment on the Isle of Man, alongside his tutor in Roman Law, who was a fellow German emigre (he set Kerr a written exam during their detention, to help pass the time). After six months’ careful consideration, the authorities cautiously concluded that a Jewish refugee was unlikely to be strongly motivated to support Hitler's war effort. In a complete reversal of his treatment at the hands of his adopted country, Kerr was not only released from captivity but also welcomed into the Royal Air Force as a volunteer, notwithstanding that he was still legally classified as an enemy. Because of that awkward status, and because of concerns about how the Germans might be inclined to deal with him if he was shot down behind the lines, he was initially prohibited from flying combat missions. So he spent the middle part of the War as a flying instructor, before he was transferred to Coastal Command in 1944 to hunt U-boats and E-Boats in the North Sea.

De-mobilised promptly at the end of the War in Europe, Kerr returned to Cambridge to complete his studies. Graduating with a first class degree, he resisted his tutors' attempts to lure him into the world of legal academia, and determined instead on a career at the Bar although, as he later confessed, he "knew practically nothing about it". Given that he had no family connections to the profession, was already in his late twenties, and had next to no money, it was a bold choice, and an indicator of Kerr's determined character. He was called by Lincoln's Inn in 1948. By then, he had finally become a British citizen. Furnished with this new status and a generous scholarship from the Inn, he cast about for a chambers in which he might do pupillage. He sought the advice of Sir Arnold McNair, eminent public international lawyer and future President of the International Court of Justice. When McNair asked what field he wanted to practice in, Kerr, who had no very clear idea, could only refer vaguely to something with an international aspect, because he was good with languages (being fluent by now in German, French, and English). On the basis of this, McNair recommended his younger brother William's commercial chambers at 3 Essex Court, assuring Kerr that the life of a shipping barrister was packed full of glamour and jet-setting trips overseas. In fact, Kerr later discovered that Willie McNair had left the British mainland only once in his life, and that his idea of international travel was an annual fishing holiday in Scotland, homeland of the McNair brothers' parents. But Kerr relied on Arnold's representation at the time to secure pupillage at 3 Essex, which had emerged from the War as the pre-eminent commercial set, after several of its previous rivals had fallen away during the conflict as a result of deaths, retirements, or their premises being bombed-out by the Luftwaffe.

Michael Kerr QC, in his room at 4 Essex Court

As a KC, Willie McNair was disqualified from taking pupils by the rules which then governed the Bar. Kerr was assigned instead to John Megaw. Since Kerr found the taciturn Megaw "agonisingly shy" and Kerr himself felt a pupil's natural deference (possibly compounded by the rugby-playing Megaw's intimidating physical presence), the two did not have a lot to say to one another. But Kerr recognised Megaw's fundamental kindness (Megaw refused to be addressed as "sir" or to accept the customary fee from pupils). And, although Kerr appalled Megaw by offering to do his typing for him, he made a sufficiently good impression to be offered a tenancy. He accepted, and settled down for a prolonged period of sitting around chambers waiting for something to happen, punctuated by the occasional trip to Edmonton County Court to watch John Donaldson, the next most junior tenant, argue a Rent Act case. There was very little work indeed for new commercial practitioners in the early 1950's, which was the quietest period in the Commercial Court's history. To begin with, Kerr had to rely on weekend law teaching and evening coaching for the Cambridge entrance exams for an income, and he came close to abandoning the Bar for a tax-free salary and generous benefits on the staff of the International Court of Justice. Like Rayner Goddard and Patrick Devlin, he got his break by being the only barrister in chambers when an urgent case came in. One August day, when everyone else had left for the Long Vacation, instructions arrived to appear at short notice in an arbitration to determine whether a shipowner was entitled to withdraw a time chartered ship for non-payment of hire. Kerr was retained to argue the case against Adair Roche's son, The Honourable T.G Roche. (In Kerr's later and rosy recollection of his big moment, he was confronted by The Honourable T.G. Roche QC, but Roche did not actually become leading counsel until the mid-'fifties.) He won, the instructing solicitor circulated good reports about him, and his career finally took flight.

Two major marine losses, both of which resulted in epic Commercial Court litigation before Colin Pearson, loomed large in Kerr’s early practice. The loss of The ‘Atlantic Duchess’ (below) was an accident……

… but Pearson held that Kerr’s clients had deliberately sunk The ‘Tropaiofors’ in order to make a fraudulent insurance claim.

From 1952 onwards, Kerr made frequent appearances in Commercial Court cases reported in Lloyd's Law Reports. He was regularly led by 3 Essex Court's more established practitioners, Alan Mocatta, Eustace Roskill, and John Megaw (McNair had gone to the Bench in 1950). But he also often argued cases alone: in 1954, for example, he argued The 'Muncaster Castle' [1958] 2 Lloyd's Rep 255, a seminal authority on the nature of the obligation of seaworthiness under the Hague Rules, at first instance before McNair. He won. (Mocatta was brought in to lead him for the subsequent appeals: they lost in the House of Lords.) Other prominent cases as a junior barrister included appearances in a pair of Patrick Devlin's most celebrated cases as a Commercial Judge Universal Cargo Carriers v Citati [1957] 2 QB 401, in which Devlin formulated his classic classification of types of repudiatory breach; and the key Hague Rules case of Pyrene v Scindia [1954] 2 QB 402, which decided that the Rules, in spite of appearances, left shipowner and shipper with freedom of contract to allocate responsibility for cargo operations.

Kerr was also instructed in two of the largest pieces of commercial litigation of the 1950's (both before Colin Pearson, who appeared to specialise in big cases as a Commercial Judge). The 'Atlantic Duchess' [1957] 2 Lloyd's Rep 55 was an oil tanker which exploded in Swansea Docks in February 1951, while discharging a cargo of Middle Eastern crude. Kerr was part of the counsel team (sandwiched between future Commercial Judges Alan Mocatta and John Hobhouse) defending the vessel's charterers against the shipowners' claim that the cargo had contained an excessive quanity of butane, making it unusually flammable and dangerous, in breach of the charter. After a thirty day trial, Pearson dismissed the claim. Even longer was the trial in The 'Tropaioforos' [1960] 2 Lloyd's Rep 469, in which Mocatta, Kerr, and yet another future Commercial Judge, Michael Mustill, appeared for a Greek shipowner whose vessel had inexplicably flooded and sunk in calm seas. After forty days and a series of brilliant cross-examinations by Eustace Roskill, leading the team for the defendant insurers of the vessel, Pearson concluded that the crew had deliberately sunk the ship on the owners' instructions in order to make a fraudulent claim on the insurance. Kerr was not so sure: when he wrote his memoirs forty years later, he could still vividly remember his client's deep and apparently entirely genuine distress at being branded a crook.

The upheavals of 1961 did not disrupt the progress of Kerr's career, and he carried his hectically busy junior workload into his new practice as leading counsel. At the beginning of the 1960's, he had been instructed as Mocatta's junior in The 'Vancouver Strikes Cases' [1963] AC 619, a group of voyage charter disputes about who bore the financial consequences of delay due to a strike at the loadport. When Mocatta went on the Bench after the hearing in the Court of Appeal, Kerr took the case over, arguing it for nine days before the House of Lords. Kerr also appeared early in his career as QC in Midland v Scruttons [1962] AC 446, in which the Lords affirmed that the doctrine of privity prevents a contracting party's employees from relying on exemption clauses in the contract (the 'Himalaya Clause' was invented to get around the decision) and The 'Hong Kong Fir' [1962] 2 QB 26, in which Kenneth Diplock revived the concept of the implied term. Later he argued The 'Heron II' [1969] 1 AC 350 and Woodhouse v Nigerian Produce [1972] AC 741 (promissory estoppel in international sales) among around a dozen Lords Appeals. He continued to be instructed predominantly in shipping and other commercial cases. But, in a sure indication of his professional eminence, he was occasionally sought out to act in other fields. He was instructed in litigation about ownership of the "Bayer" logo and the effect of the division of Germany on the assets of the Zeiss company. In perhaps his most distressing case, he acted for the manufacturers of the morning-sickness pill Thalidomide, which damaged the physical development of unborn children.

One of the more physically presentable of the Commercial Court's male Judges (albeit that the competition has seldom been fierce), Kerr was tall and solidly built, with blue eyes and a piercing gaze. All of this gave him a degree of presence which was a useful attribute for an advocate, although his style was generally understated, his submissions made in a quiet but clear voice, and rooted in sober analysis rather than oratorical flourish. He was troubled from an early stage by hearing problems (initially, but incorrectly, attributed to his wartime service in noisy bombers, so that he was paid compensation by the government), but this did not hold him back. In addition to work as counsel, he was increasingly in demand as a commercial arbitrator. Most prominently, he was appointed as sole arbitrator in the Dawson's Field insurance arbitration, which resulted from the co-ordinated hijacking and subsequent destruction on the ground of three airliners. The key question was whether the loss was a single event or a series of events, an issue which was critical to how much the insurers were liable to pay. Although arbitral awards are generally confidential, Kerr's decision was subsequently publicised, and came to be regarded by the insurance industry as an authoritative statement of the law.

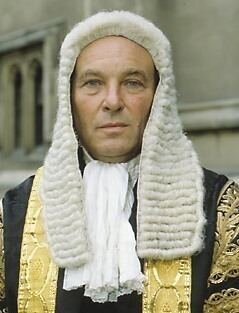

Kerr on the day of his swearing-in as a High Court Judge in April 1962, betraying no sign of the uncertainty which he had felt over whether his future lay on the Bench or in the City.

During 1970, Kerr received two contrasting employment offers: from Lord Chancellor Hailsham, of a place on the High Court Bench; and from a merchant bank, of a career in the City of London. Sensibly hedging his bets, he continued in practice for the best part of another two years, before opting for the High Court. He was appointed to the Queen's Bench in April 1972 and, within a few weeks, was hearing an arbitration appeal in a voyage charter case in the Commercial Court (The 'Angelia' [1972] 2 Lloyd's Rep 154). Kerr was a great success in the Court, where he decided a clear majority of his reported cases. They included Harbottle v National Westminster Bank [1978] QB 146, in which Kerr established the principle that the balance of convenience will almost always be against restraining a bank from making payment under a guarantee or letter of credit, and The 'Michael' [1979] 1 Lloyd's Rep 55, a forty day marine insurance claim with shades of The 'Tropaioforos', since the insurers contended that the owners had deliberately sunk the ship in order to collect the insurance money. Kerr decided that there had been a deliberate sinking, but absolved the owners from blame, holding that the guilty party, Second Engineer Komiseris, had acted on his own initiative, in the hope that the owners would reward him for doing away with an unprofitable ship. (Remarkably, The 'Michael' was Mr Komiseris's second ship sinking. He had previuously been implicated in the mysterious loss of The 'Gold Sky' [1972] 2 Lloyd's Rep 187, and although trial Judge Alan Mocatta was not convinced that that ship had been scuttled, Mr Komiseris later admitted that it had been.) Kerr was also the first instance Judge in The 'Siskina' [1977] 1 Lloyd's Rep 404. His refusal to approve a writ claiming a Mareva Injunction was upheld in the House of Lords, where Kenneth Diplock, plainly convinced that first-instance Judges could not be trusted with broad discretionary powers, took the opportunity to slap a severe restraint on the injunction jurisdiction.

As Judge in charge of the Commercial Court in 1977, Kerr introduced a scheme "to provide an extended service" by ensuring that one Commercial Judge would be available to hear routine business throughout the whole of September, a month during which the Court was traditionally more or less closed as part of the Long Vacation: [1977] 1 Lloyd's Rep 455. He also sat in a handful of Admiralty cases. Conscientious and quick-minded, Kerr also had the gift of sound judgment, and was generally regarded as pleasant to appear before. But he was less at home with Queen's Bench work outside the commercial sphere. He disliked criminal litigation (of which he had had negligible experience at the Bar), and was impatient with what he regarded as the petty formalities of life on Circuit. He delivered a few reported judgments about employment and tort, and he did his bit in the Criminal Division of the Court of Appeal, but without any real enthusiasm.

Kerr as a Lord Justice of Appeal

Although highly regarded as a commercial trial Judge, Kerr did not acquire a reputation as a great jurist. While he had a thorough professional understanding of commercial law, he did not find the law hugely interesting. He confessed in his memoirs that he had never read a full case report at Cambridge, and that his legal knowledge was largely crammed from textbooks. Moreover, he was of the school of thought that the answer in any case depended first and foremost on the facts and, while his judgments often contained clear and concise statements of the existing law, he contributed relatively little to the development of legal principle. Kerr was therefore in many ways an odd choice as Chair of the Law Commission. He accepted the appointment in 1978 reluctantly, but on the basis of a promise that he need only serve three years and would then be promoted to the Court of Appeal. That bargain was honoured, and Kerr duly became a Lord Justice in 1981.

His time in the Court of Appeal was the happiest part of his judicial career. He enjoyed the variety of cases and like the collegiate atmosphere. He got on well with veteran Master of the Rolls and head of the Court's Civil Division, Lord Denning: Denning chose Kerr to sit with in his final case, George Mitchell v Finney Lock Seeds [1983] QB 284. Kerr was also hugely relieved that he longer had to try crime on Circuit. He sat on significant commercial appeals, including Rover v Cannon [1989] 1 WLR 912, which dealt with the legal fallout from a contract with a company which had not yet been properly incorporated Babanaft v Bassatne [1990] Ch 13, which expanded the Mareva jurisdiction.

In CTI v Oceanus [1984] 1 Lloyd's Rep 476, where the appeal lasted twenty-eight days, he reviewed the insurance law authorities on material non-disclosure in depth, and concluded that his own first-instance decision in Berger v Light Diffusers [1973] 2 Lloyd's Rep 442 had been largely incorrect. (A decade later, his former pupil, Michael Mustill, endorsed Berger, and partly overruled CTI: Pan Atlantic v Pine Top [1995] 1 AC 501.)

But the work was immensely hard. Under the relaxed management of Denning, who liked to allow every hearing to run its course, without pressing the pace, the Court had acquired a large backlog of appeals. The Lords Justices had to deal with a relentless flow of cases, with little time between hearings for consideration or preparation of reserved judgments. Tired out, Kerr began to suffer health problems, undergoing a back operation and then a triple heart bypass. He hoped to escape to a less pressured working atmosphere in the House of Lords. But when former fellow Commercial Judge Robert Goff, who was five years younger, was made a Lord of Appeal in 1986, Kerr recognised that he would not be promoted. He stepped down from the Bench in 1989. But it was not retirement. Kerr had kept in touch with the world of arbitration while on the Bench, serving as President of both the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators and of the London Court of International Arbitration. The LCIA was the successor to the City of London Chamber of Arbitration, which had been founded in 1891 to provide the City with the sort of speedy and efficient dispute resolution which it complained that it seldom got from the Courts. The institution had never been a great success, and by the 1980's it was virtually moribund. Kerr devoted himself to reviving its fortunes, helping to draft new rules and procedures and travelling the globe to promote London as a centre for international commercial arbitration. Within a few years, the LCIA had become one of the world's leading commercial dispute resolution organisations, and Kerr was one of its busiest arbitrators. He also sat as a Court of Appeal "retread" when he could spare the time, making his final appearance in 1996.

The first Commercial Judge to publish his memoirs, Kerr produced a private-circulation version of 'As Far As I Remember' in 1994. A much expanded edition was published in April 2002, shortly after his death from heart failure. Sadly for legal enthusiasts, the author declared that "I have taken a vow not to write about my endless cases". The main focus of the book was instead on his family.

Michael Kerr was married twice. His divorce from his first wife in 1982 was thought to be another first, unprecedented for a serving High Court or Court of Appeal Judge, and merited an entry in The 'Times. He had five children. His eldest son, Sir Timothy Kerr, a barrister and QC like his father, was appointed a Judge of the Queen's Bench Division in 2015.