"Such is the unity of all history that anyone who endeavours to tell a piece of it must feel that his first sentence tears a seamless web."

Pollock & Maitland, 'The History of English Law before the time of Edward I'

Most English legal history is characterised by evolution rather than revolution. Doctrines and institutions usually emerged slowly as a result of cautious and incremental change, not fully-formed as the product of dazzling intellectual breakthrough. In the nature of this process, it sometimes happened over time, and sometimes over a very long time, that innovations had consequences more far-reaching than their creators planned or anticipated. Henry II's ministers may not have intended to accelerate the decline of feudal and local courts when they introduced improved procedures for disputes about land. But their reforms nevertheless had that effect, and the resulting rise of the royal courts to a position of judicial dominance made possible the development of a law which was genuinely "common" to the whole kingdom. Similarly, the 14th Century judges who sanctioned the first minor extensions to the action of trespass cannot have anticipated that from such small beginnings would ultimately develop not only a wider common law of tort but also, more remarkably, a common law of contract.

The rise of the Commercial Court may look like another example, on a less grand scale, of the unintended consequences of apparently insignificant change. To outward appearances, the world's leading forum for the resolution of commercial disputes owes its existence to a minor alteration to the administrative arrangements of the High Court in the last decade of the 19th Century. In this case, however, the appearance is deceptive. The innovation was certainly modest in form, and deliberately so. But the small yet determined group of Queen's Bench judges who were responsible for it had very clear ideas about what they wanted to achieve. They were responding to a profound crisis in their Court, and they had far-reaching ambitions: to lure commercial parties away from the temptations of arbitration, to reverse a disastrous decline in commercial litigation, and to restore the Queen's Bench's battered reputation.

A Diversity Of Royal Courts

"This arrangement, seemingly impracticable to modern eyes, was a feature of English public life for five centuries."

Sir John Baker, 'An Introduction To English Legal History'

The state of crisis which undoubtedly afflicted the Queen's Bench Division of the High Court at the end of the 19th Century is an oddity. The Court's morale and reputation ought to have been in the rudest health, for only a few years had passed since the Queen's Bench had emerged as the outright victor in an ancient and three-cornered judicial rivalry. For almost the whole of its existence, the Queen's Bench had been just one of three central common law courts, periodically fighting the other two for business in times when levels of litigation declined. But by 1880, the Queen's Bench had seen its rivals off and become established as the sole national common law court.

The number and diversity of courts which feature in the history of English law is one of the many aspects which are likely to surprise anyone approaching the subject for the first time. It was natural that there should be many courts in the land-centred economy and hierarchical society of the first centuries after the Norman Conquest, because there were many lords and it was every lord's duty and (lucrative) right to provide a court for his tenants. But even after most of these feudal courts withered in the later Middle Ages, the legal landscape of England & Wales was populated by a multitude of judicial tribunals. Courts of purely local jurisdiction existed in the counties and in numerous manors, cities, boroughs, and Church dioceses. More surprising is the number of central courts, ultimately emanating from the power of the Crown, and therefore of national jurisdiction. In addition to the Court of Chancery, which owed its origins to interference by meddlesome royal civil servants in the works of other courts, and which slowly evolved into a court in its own right during the 14th and 15th Centuries, there were such exotic and specialist tribunals as the Star Chamber, the Court of Requests, and the Courts of the Admiral and the Marshal. More surprising still is that, for most of English legal history, common law civil jurisdiction in cases about land, contract, and tort, was divided between three central courts: the Exchequer of Pleas; the Common Pleas; and the King's (or Queen's, depending upon the monarch) Bench.

The coat of arms which hangs in courtrooms throughout England & Wales is a reminder that judicial authority historically derives from the Crown.

These three courts emerged gradually from the curia regis. This curia was the original royal "court", but in the governmental sense of the retinue of counsellors and administrators who advised the King and implemented his decisions, not in the judicial sense of a tribunal staffed by professional judges. The curia did have what would today be recognised as judicial functions, since the King, like other feudal lords, was obliged and entitled to provide dispute resolution services for his tenants. He also felt entitled to intervene in other disputes where royal interests were involved or which were otherwise sufficiently important to warrant his attention, or as a royal favour to the parties. But the curia's functions extended beyond the resolution of individual disputes into all areas of central government, and its judicial activities were not originally regarded as distinct: the "court" which participated in royal adjudications was the same institution which assisted the King with his other business.

English Kings in the generations after the Norman Conquest were almost constantly on the move. The King of England was also ruler over Continental possessions which required his personal attention, and, even when in England, the King generally considered it advisable to remain mobile, the better to supervise the affairs of the realm. It was natural for royal business and the curia in which it was conducted to follow the King. However, aside from the logistical challenges involved in hauling the curia, its staff and records about the country, a system in which all aspects of central government were on permanent tour was not always conducive to efficient administration. A suitor who wanted a royal decision on any matter must first find out where the King was and then attend upon him. But in days when neither news nor people could travel faster than a horse, the King's location was not always certain. Even if a suitor found out where the King was and set off to seek an audience, there was every chance that the royal household would have moved on before he arrived.

Moreover, the business of government had an inherent tendency to expand. In the field of adjudication, for instance, royal justice came to be seen as superior to feudal and local justice, or at least to be backed-up with more effective sanctions, and the number of litigants seeking access to the royal courts gradually became too large for all of their cases to be dealt with by a wandering monarch and his closest confidants.

From Curia To Court

"Common pleas shall not follow our Court about, but shall be held in some fixed place."

King John, 'Magna Carta'

Practical considerations such as these eventually forced changes in how royal business was conducted. Some of the curia's tasks were delegated to specialist groups of personnel, and, over time, these slowly developed into separate institutions. The Exchequer was the first. It was inconvenient for the contents and officials of the royal treasury constantly to roam around the country following the King. During the first part of the 12th Century, the civil servants responsible for the collection and custody of royal revenues settled permanently in Westminster, evolving into a distinct government department. By the end of the same Century, the Exchequer had acquired recognisable judicial functions in revenue cases, which it exercised in the form of the court of Exchequer of Pleas.

Meanwhile, Henry II's reign saw increased delegation of royal justice to a body of trusted advisers. The first delegates were drawn from the curia. They were laymen, rather than professional lawyers, for there was no legal profession at the time (although many were officers of the Church who would have had training in ecclesiastical law). But, during the 13th Century, this group of educated delegates evolved into a body of full-time judges, drawn from the emerging legal profession. Delegated royal justice retained a strong mobile element. Under the eyre system, which endured in one format or another until the 14th Century, the kingdom was divided into Circuits and royal judges toured through each, visiting the major population centres in turn. But a static element also developed: by the 1190's, a settled judicial court, known as "the Bench", was established at Westminster.

Inner Temple Library owns a set of illuminations dating from about 1460 and illustrating the four main Royal Courts. This is the Exchequer.

History has not generally been kind to King John, but important developments in the English judicial system date from his reign.

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Henry II's bookish youngest son, John, took a fiercely intelligent interest in government and administration. After losing his ancestral Norman possessions to the French, he could also devote more effort to English affairs than either his father or his elder brother: Henry had been constantly distracted by the demands of the continental Angevin empire and the intrigues of his sons, who were always revolting; while Richard I was a feckless jailbird who preferred playing crusader to the proper discharge of his royal responsibilities. Freed from such distractions, John used some of his extra time by reviving the practice of royal participation in cases before his Court. As a result, the justices of the Bench were compelled to leave Westminster and go back on the road as part of John's retinue. This development was not popular. Following the King put litigants to considerable financial and geographical inconvenience. And John's return to the old ways was just the sort of assertion of royal right and privilege which his Barons, the unruly and quarrelsome nobles of the realm, found increasingly tiresome. One of the Baronial demands to which John submitted by Magna Carta in 1215 was that "common pleas", cases in which the Crown had no direct interest, should no longer follow the King's unpredictable path around the country, but should be heard at some specified place.

This provision may have had little immediate impact. John died within 18 months of Magna Carta leaving the 9 year old Henry III as heir, and there was no question of common pleas or any other cases having to follow the King while Henry remained underage. But Magna Carta acknowledged a distinction in principle between pleas of the crown, in which the King's interests were engaged, and common pleas, in which they were not, and the division became more entrenched as Henry's reign progressed. By the middle of the 13th Century, the original Bench was splitting into two distinct Courts: the King's Bench, for pleas of the crown, particularly crime and its civil counterpart, tort, both of which were regarded as involving an affront to the peace and order of the realm; and the Common Pleas, for purely private disputes about land, debts, goods, and contracts. True to the spirit of Magna Carta, the Common Pleas acquired a fixed base at Westminster, where the Judges sat during settled Legal Terms. The King's Bench remained mobile for a few decades. But, by the end of the Century, it too became (more or less) permanently settled at Westminster. Now there were three different royal courts, Exchequer of Pleas, Common Pleas, and King's Bench, conducting common law business under one roof at Westminster Hall.

Not every aspect of judicial business was conducted at Westminster. Because the three common law Courts derived their jurisdiction from the authority of the King, their writ naturally ran throughout the land. But parties, witnesses, and jurors (who were expected to come from the area where the case arose, and to have local knowledge) could not sensibly be expected to journey to London by horse over unmade roads from every corner of England & Wales. So trials were conducted locally: the country was divided into four (later six) Circuits, each of which was regularly toured by Judges outside the Legal Terms. But, while individual Judges went Circuit to obtain jury verdicts, the Courts' permanent elements, their offices, staff, and constantly growing archives of records, laboriously written out by hand on animal skins, remained in Westminster. This was where London cases were tried. It was also where the Judges of each Court (typically at least four) sat as a group ("in banc") to hear argument about and decide points of law, pleading, procedure, and other questions which were not matters for a jury.

The Common Pleas.

In theory, the apparently pointless division of central royal justice could be justified on the grounds that the three courts dealt with different types of litigation. The Exchequer's focus remained on revenue cases; the King's Bench dealt with crime and tort; and the Common Pleas' primary caseload related to disputes about land and actions for the recovery of debts and goods. But the lines of demarcation were never absolute. For one thing, the Common Pleas' jurisdiction in civil cases was unlimited in practice, although the Court, which was busier than either the Exchequer or King's Bench for much of its history, was generally content to limit its reach in practice. More significantly, the Exchequer and King's Bench were both adept at finding ways to expand their jurisdiction, and thereby increase the fee income which was the inevitable accompaniment to any exercise of judicial authority.

The King's Bench was particularly innovative in this respect. Through the series of fictions associated with the so-called Bill of Middlesex, it asserted its right to hear ordinary debt claims (ie cases in which there was no royal interest: if the Crown was involved, the case was supposed to go to the Exchequer); by developing the law of tort through the action on the case, it created forms of action which could be used to try cases about title to land; and by generating assumpsit out of the action on the case, it acquired a general contract jurisdiction. In principle, these were "common pleas" which were meant to be the exclusive preserve of the Court of that name. By Tudor times, however, the King's Bench's civil jurisdiction was almost as wide as that of the Common Pleas.

The Exchequer of Pleas was slower to see the attractions of fictitious devices and procedural dodges. But it eventually began to adopt these in order to justify hearing debt cases in which there was no royal interest.

These developments were probably driven by consumer demand more than judicial activism. For example, it was cheaper to start a debt claim by Bill of Middlesex in the King's Bench than by writ in the Common Pleas, and ordinary creditors were attracted by the supposedly superior enforcement procedures in the Exchequer of Pleas. But, whatever the precise mechanism, the civil jurisdictions of the three royal common law courts had become very close to identical by the end of the 16th Century. One consequence was that the King's Bench and the Common Pleas in particular - and the distinct groups of lawyers who practised in them - competed for business and fee income when, as happened from time to time, the overall volume of litigation declined.

The King’s Bench

Triumph.....

"Question put. The House divided - Ayes 110; Noes 178."

House of Commons, vote on an unsuccessful motion to retain the Common Pleas and Exchequer of Pleas, February 1881

Ultimately, the King's Bench emerged victorious from these territorial squabbles. In 1867, a Judicature Commission was appointed to consider whether the continued existence of three separate but overlapping jurisdictions rooted in medieval feudal history was the best way to serve the needs of a modern trading nation. The Commission’s conclusions led, after much wrangling and resistance, at one time or another, from all corners of the judiciary and legal professions, to the Supreme Court Of Judicature Acts of 1873 and 1875. When these came into force in 1875, they terminated the independent existence of the three common law courts (and various other ancient national courts) and replaced them with a new and unified High Court of Justice.

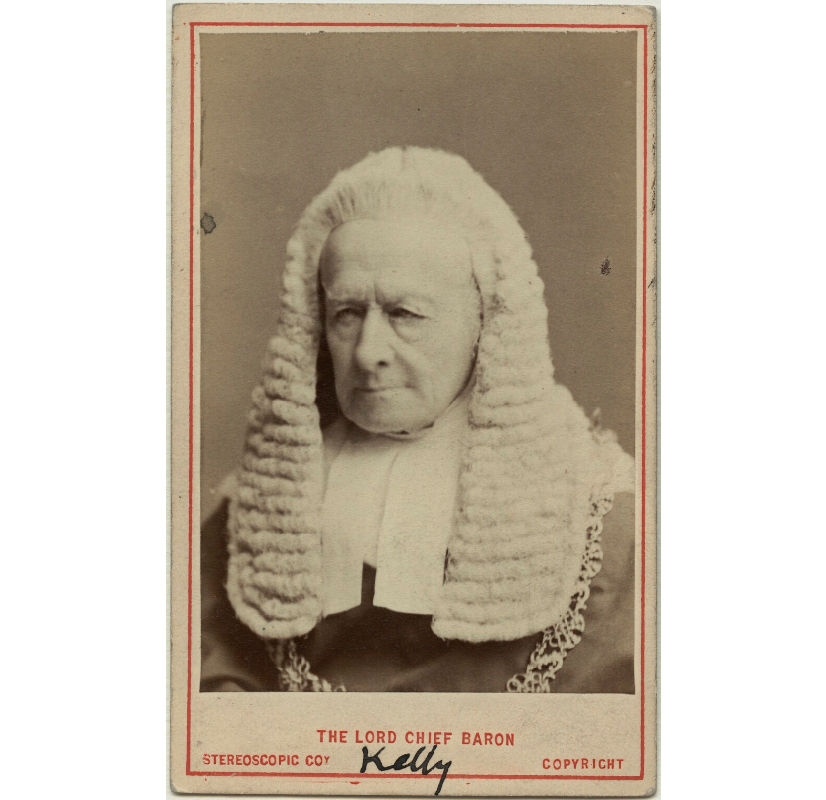

This new entity was originally composed of five divisions: one corresponding to the meddlesome Chancery; an entirely new Probate, Divorce & Admiralty Division, which inherited the family work of the old church courts plus the Admiralty jurisdiction (which, like ecclesiastical law, took Civil - ie, Roman - law as its primary source); and divisions corresponding to each of the Exchequer of Pleas, the Common Pleas, and the King's Bench (by now the Queen's Bench). But this last part of the scheme was purely short-term, and was driven by expedience. Each of the three common law courts had its own president. Merging the courts into a single division would have meant demoting or retiring at least two of them. This would have been awkward in any circumstances. But in 1875, all three presidents were former MPs who had held government office as Attorney-General: Sir Fitzroy Kelly, Chief Baron of the Exchequer of Pleas, as a Conservative, and Lord Coleridge and Sir Alexander Cockburn, Chief Justices of the Common Pleas and of the King's Bench respectively, as Liberals. (Cockburn, a colourful personality who once escaped bailiffs through a window of a court where he had been appearing as counsel, should have been made a peer like Coleridge, but Queen Victoria objected to his "notoriously bad moral character".) To avoid the political and social embarrassment of reducing the status of any of these grandees, all three were kept on as heads of division until two of them should die off or retire, leaving one to acquire priority by right of survivorship.

Here, Coleridge had the advantage of being youngest by 18 years. When Kelly and Cockburn had the good grace to die within two months of one another in autumn 1880, the Exchequer and the Common Pleas were both done away with at a single stroke. By an Order in Council passed on 16th December 1880, they were abolished after more than 600 years of existence, leaving the Queen's Bench Division of the High Court as the sole remnant of the ancient common law jurisdictions. Coleridge became Lord Chief Justice of England by the judicial equivalent of natural selection. He endured for another 14 years as a hopelessly ineffectual head of the Queen's Bench, which gave him the opportunity to play an inglorious role in the story of the creation of the Commercial Court.

An embarrassing side-effect of the Judicature Acts was that, although they were intended to reduce the number of common law Courts from three to one, the judiciary was still left with two Chief Justices and a Chief Baron. Lord Coleridge (left) eventually outlived Sir Alexander Cockburn and Sir Fitzroy Kelly to emerge as Chief Justice of England. In terms of ability, it was not a case of survival of the fittest.

In the meantime, the common law judiciary was left two judges short by the deaths of Kelly and Cockburn. In March 1881, new appointments were made to the Queen's Bench to fill the gap. The unfortunate Sir Henry Mather Jackson QC, baronet, and lately Liberal MP for Coventry, died within a matter of days, without taking office, aged only 49. The 'Law Times' consoled its readers that "it would be affectatious to say that his talents were of the first order, and it is not probable that on the bench he would have shone conspicuously: indeed, we believe that his appointment did not excite any high anticipation at the Common Law Bar". James Charles Mathew was altogether more highly regarded, and fared rather better: he had been the busiest junior barrister in commercial practice and, in the course of a judicial career which would last more than 20 years and end in the Court of Appeal, he would effectively create the Commercial Court, becoming its first Judge and its most important formative influence.

...Decline...

"Lord Mansfield's retirement initiated a period of quiescence. His rapid and intensive cultivation of the law seemed to deserve, and his insistence on rationalisation to sanction, an ample of interval of digestion. The Judges, released from the pressure of a superior personality, were willing to resume the tranquillity, congenial to their age and temper, from which they had, with reluctance, been aroused."

C.H.S. Fifoot, 'Lord Mansfield'

In the very hour of the Queen's Bench's victory in one jurisdictional struggle, it seemed doomed to total defeat in another. Coleridge took office at a time when the Court's once glowing reputation for the resolution of commercial cases had sunk to unprecedented depths of degradation. Commercial litigants in droves were demonstrating their disgust by chancing their arm in arbitration. The Queen's Bench's commercial specialists, both Judges and practitioners, began to fear that their Court would never regain this prestigious business unless drastic steps were taken. But, in the short term at least, things were fated to get even worse before they got better.

This was a strange state of affairs, because the Court’s history of handling commercial cases was a long and largely successful one. Indeed, the first reported case in which liability was based on an assumpsit, The Humber Ferry Case of 1348, was a King's Bench action for failure properly and carefully to carry and care for a cargo. However, notwithstanding this early foray into the field of carriage of goods, the medieval Court did not develop a distinct body of commercial law. Much commercial litigation was presumably conducted away from the royal courts, in the townships and boroughs where merchants held their markets and fairs. But there was also a surprising psychological reason: the common law Courts, perhaps nervous of setting bad precedents, were profoundly reluctant to decide points of legal principle. Trial was by jury in civil as well as criminal matters, and the invariable judicial preference was simply to leave the entire case to the jury at large, without differentiating fact from law. The trial judge might give the jury some general guidance on the law, but this did not form part of the record of the case, and was not a useful vehicle for developing and expounding legal doctrine. On the comparatively few occasions when the judges were forced into to deciding a point of law, the form of the issue tended to be procedural (for example, whether the wording of a writ was valid) rather than substantive.

In theory, a pure point of law might arise on the pleadings. If a party "demurred", by admitting all of the facts which the other side alleged, but pleading that those facts did not support a claim (or a defence) as a matter of law, there was no need to summon a jury, and the Court in banc would rule on the legal point. In practice, this happened comparatively rarely. For one thing, only a brave - or eccentric - litigant would stake everything on a demurrer without trying to win over a jury with a good story on the facts. For another, the peculiar process of common law pleading discouraged it. Counsel stated their clients' cases orally before the Court, with opposing counsel and the Judges freely intervening with objections or comments. A plea did not become binding until it was formally written into the record. Before that happened, any novel or difficult point would have been analysed in oral debate. The Judges, with their aversion to deciding points of principle, actively discouraged demurrers by expressing their provisional views on legal points, a sort of early neutral evaluation. Any counsel tentatively advancing a point of law and detecting judicial resistance would naturally either find some different way of putting the case or advise settlement. The result was that, while points of law certainly arose for debate in the common law Courts, it was relatively unusual for them to be definitively decided in a way which would set a precedent or contribute to the development of coherent legal doctrine.

The medieval system fell away in Tudor times, when oral pleas were superseded by written pleadings. These were prepared outside court and became binding before any judicial scrutiny, which increased the prospect of points of pure law arising on the pleadings. Around the same time, the common law Judges, embracing the intellectual spirit of the Renaissance, began to accept that it was part of their job to decide points of principle and develop the common law. Demurrers still had the disadvantage that the party demurring had to forego jury trial. But other procedures, particularly special verdicts (in which the jury dealt only with the facts, leaving the Court to apply the law) and motions in banc (by which general verdicts, in which the jury dealt with both law and fact, could be challenged on a point of law) were made more freely available, so that points of law could be brought before the Court in banc in Westminster Hall even after the jury had delivered a verdict at a trial.

Lord Mansfield was a founding figure of modern English commercial law.

These developments made it easier for the Courts to develop commercial law as a coherent doctrine. But the King's Bench's reputation for excellence in this field was really cemented during the Chief Justiceship of Lord Mansfield, from 1756 to 1788. William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, was born into an eminent Scottish family sympathetic to the deposed Stuart dynasty, but served Hanoverian Kings, as Law Officer and Judge, for 45 years. An instant success at the London Bar, the progress of his career was marked out by the increasing grandeur of his home addresses: Lincoln's Inn Fields, Bloomsbury Square, and Kenwood House, complete with its own dairy. Becoming MP for Boroughbridge (a "rotten borough" whose MPs were effectively selected by the Dukes of Newcastle: the constituency was abolished by the Great Reform Act of 1832), Mansfield followed the customary career path of the ambitious and successful barrister-MP: Solicitor General, Attorney-General, Chief Justice of the King's Bench.

Mansfield brought to his judicial office a vitality which was alien to the settled working practices of the King's Bench. On his first day in office, he astonished the Court by delivering judgment at the conclusion of the argument.Common law Judges generally considered it proper to take a lengthy period for mature reflection, and even to allow points to be fully argued all over again, before hazarding a decision. Throughout his time on the Bench, Mansfield sat long hours to get through the Court's caseload. He worked efficiently, and sought to promote efficiency in others: he was known to open the newspapers if counsel started repeating points.

Mansfield was interested in all areas of his Court's work, but his name is forever linked with commercial law. A committed free trader (it was said that he regarded an outright ban on trading with the enemy as an unwarranted interference) in an era of expanding international commerce, when Britain, and London in particular, was the world's leading trading and financial centre, Mansfield sought actively to support the City's business. (Mansfield himself had a keen eye to extra-judicial business opportunities¸ and enhanced his fortune with a profitable side-line in money-lending.) Under his leadership, the King's Bench tried London comercial cases at the Guildhall, in the heart of the City, relieving the commercial community of the cost and trouble of the journey to Westminster Hall. The invigorated procedural pace which he fostered enabled commercial cases to be tried quickly. Mansfield also made liberal use of special juries, empanelling City merchants who were familiar with mercantile customs. But while Mansfield relied on specialist jurors to deliver verdicts on points of commercial practice, he firmly believed that it was the Court's function to declare, clarify, and develop the law. In his time, a steady diet of points of commercial law came before the King's Bench judges after special verdicts or on motions in banc. The result of Mansfield's efforts was a burgeoning of commercial litigation in the King's Bench, and a flow of judicial decisions developing the law of contract generally and the specialist commercial fields of sale of goods, bills of exchange and financial instruments, and insurance in particular. Mansfield's King's Bench even took early steps towards a law of restitution, and enjoyed such flourishing business that the Common Pleas came to be viewed as rather a backwater by comparison.

But in law just as much as in other fields of human endeavour, the restless energy exhibited by pioneers often fails to outlive them. After Mansfield's retirement in 1786, his less vigorous judicial colleagues manifested a tendency to return to old ways, and King's Bench litigation reverted to a more sedate pace as hearings became slower and the intervals before delivery of judgments became longer. Some of the Court's settled customs contributed to these developments. In particular, the ancient practice of sitting in banc to rule on issues of law had the advantage that the full intellectual weight of the Court was brought to bear on novel and difficult questions. But it inevitably limited judicial productivity, since each Judge had to attend every hearing when the Court sat in banc. This problem was mitigated to an extent by the system of legal terms. Annual sittings at Westminster Hall were divided into four terms of just three weeks each. This left the Judges free to preside over jury trials (which they did singly, not in banc) for much of the rest of the year, which helped maximise the number of trials which could be listed (although there were recurrent complaints that judicial vacations were excessively long). But the fact that only 12 weeks per year were allotted for the determination of issues of law arising on motions in banc, special verdicts, or demurrers inevitably created a backlog. By the 1830's, some 300 motions of various kinds were waiting their turn for hearings in banc, and the waiting time could be up to two and a half years. The Court's problems were exacerbated by a general increase in litigation during and after the second half of the 18th Century. The King's Bench attracted a greater share of this work than the other common law Courts (281,109 actions were commenced in the King's Bench in the first part of the 1820's, compared to 80,158 in the Common Pleas and 37,197 in the Exchequer), and it was becoming increasingly apparent that the King's Bench was struggling to cope with its caseload.

The Guildhall around the 1750’s when Lord Mansfield tried commercial cases there.

By way of reaction, arbitration clauses became increasingly common in commercial contracts. It is a telling indication of dissatisfaction with the King's Bench that commercial parties turned increasingly to arbitration in spite of the fact that its potential pitfalls were well known. The applicable law was complicated by the existence of no fewer than three distinct types of arbitration.

First, there were references based on a bare submission agreement, which might take the form either of a general agreement to submit any future disputes arising out of a particular contractual relationship to arbitration, or of a more limited agreement to submit a particular dispute which had already arisen. Arbitrations based on a bare submission agreement were precarious affairs. The common law conceived the relationship between the parties and the Tribunal in terms of mandate. An unfortunate consequence of this analysis was that the mandate could be unilaterally revoked, which meant that either party could derail a reference by withdrawing the Tribunal's authority before it issued an award. (As between the parties themselves, revocation generally constituted a breach of contract, but any claim for damages would have to be brought by way of fresh proceedings.)

Second, there were references based on an order (known as a "rule of Court") made in the course of existing proceedings before one of the common law Courts. If both parties consented, the Court could, by making a rule, refer particular issues, or indeed the whole case, to an arbitrator. This was similar to a contractual agreement to refer an existing dispute to arbitration. However, unlike a bare submission, a reference based on a rule of Court, because it was backed by a Court order, was effectively irrevocable (since a refusal to proceed with the arbitration was a contempt of Court, punishable by imprisonment). A rule of Court effectively allowed the Court to delegate decision-making responsibility, but the Court proceedings remained in existence, and the arbitrator's ultimate decision would be converted into a judgment of the Court in order to carry it into effect. The procedure was useful in cases which involved specialist subject-matter beyond the knowledge of the typical judge or an ordinary jury. It appears to have become relatively common in commercial cases tried on Circuit (special juries of merchants were not readily available outside the City of London). This may in itself have contributed to the increasing adoption of arbitration clauses, since some commercial parties must have concluded that, if a Court case was likely to be referred to arbitration in any event, they might as well opt for arbitration from the outset, and bypass the Courts altogether.

Third, there were references based on a statute of 1698. (The statute was unnamed, but it became known to history as "Locke's Act" after the philosopher John Locke, who, in his capacity as a member of the Board of Trade, played a leading role in its creation.) This statute enabled a party to a suitably-worded arbitration agreement to obtain a rule of Court upon presentation of an affidavit, without having to start a fully-fledged Court action. This third form bridged the gap between the first two, providing the advantages of irrevocability and of a relatively simple way of converting an award into a judgment, while avoiding the inconvenience and expense of having to start Court proceedings as prelude to the arbitration.

John Locke is better remembered today for ‘An Essay Concerning Human Understanding’ and other philosophical works than for his innovations in the field of English arbitration law.

Although references based on rules of Court or the statute had advantages over those based on bare submission agreements, it was well-recognised that results might be haphazard in any form of arbitration, since commercial arbitrators could not be relied upon to apply the law correctly or to follow procedures which were consistent with judicial notions of fairness. (Having a lawyer on the Tribunal might help to promote legal and procedural competence, but lawyer-arbitrators were said to be prone to prioritise their other professional commitments, causing delay, while arbitrators of all types were sometimes accused of charging excessive fees.) And if something did go wrong in an arbitration, it could be extremely difficult to put it right. If the reference was based on a rule of Court or the statute, the common law Courts had power to intervene in the event of misconduct by the Tribunal or procedural irregularity. They had no such power if the reference was based on a bare submission agreement (although limited equitable relief was available in Chancery). The common law Courts could only intervene for error of law if the error appeared on the face of the record, which meant that a Tribunal's legal analysis could not be challenged if the reasons did not form part of the Award. The effect of these principles was that a reference based on a bare submission was usually immune from supervision by the common law Courts. And, where the common law Courts were entitled to intervene, their only powers, whichever the basis for the reference and whatever the nature of the Tribunal's mistake or misconduct, were to set the award aside or refuse to enforce it. There was no power to remit an award to the Tribunal for further consideration. So a successful challenge to an award raised the prospect of the arbitration starting all over again.

Yet, for all that arbitration did not have a particularly secure legal footing, many commercial parties believed that arbitrators would deal with disputes quicker and cheaper than the Courts. Whether or not the belief was generally correct is not clear. But the very fact that it was widespread was itself an indictment of how defective Court processes had become.

...And Fall

"The beneficial reforms in the law effected nearly twenty years ago by the Judicature Acts were followed by unforeseen drawbacks. Lord Selborne and Lord Cairns - the authors of the change - were illustrious equity lawyers, accustomed to the Court of Chancery and its ways; and the Chancery procedure of the time was rather suited to the slow and stately movement of great and expensive suits than to less complicated common law actions... In every direction, the judicature reforms turned out to have introduced into the Queen's Bench Division a machinery too delicate for its necessities.”

'A Member of the Bench' (Bowen LJ), The Times, August 1892

"Suffer any wrong that can be done you rather than come here!"

Motto of the Court of Chancery (first recorded by Charles Dickens, 'Bleak House')

Ironically, the rate of decline of commercial work in the Queen's Bench was accelerated by the very reforms which had secured the Court's victory over the Exchequer of Pleas and Common Pleas. There were a number of reasons for this phenomenon.

First, a central part of the scheme of the Judicature Acts was that the new and unified High Court should have a new and (more or less) unified procedure, which was contained partly in the Acts and partly in Rules of the Supreme Court which were made under the Acts. (These replaced earlier rules made under the Common Law Procedure Acts, which had previously applied in the three common law Courts.) Reformers had long argued that common law procedures were slow and encouraged litigants to take purely technical points, and claimed that the introduction of a new and rational set of rules would stop cases being side-tracked into procedural debates which were wholly irrelevant to the merits. In practice, the introduction of a whole new procedural code generated an explosion of satellite litigation, as lawyers and Judges grappled with numerous doubtful issues, usually quite irrelevant to the merits of the cases in which they arose, about what various provisions of the Acts and Rules might mean. By the 1890's, there had been more than 7,000 decisions on points of procedure since the Judicature Acts. Since it was a theme of the Common Law Procedure Acts and the Rules of the Supreme Court that the outcomes of cases should not usually be determined by formal or procedural matters, the majority these decisions did not resolve the cases in which they were decided. Instead, they added cost and delay to the resolution of the underlying dispute. The problem of satellite litigation afflicted all Divisions of the High Court, and affected all types of litigant. But it was especially off-putting to commercial litigants, who particularly valued efficiency and economy in dispute resolution. (As though to demonstrate that no idea is too optimistic to be repeated, the Courts of England & Wales marked the end of the 20th Century with another new procedural code. A generation later, the Civil Procedure Rules which replaced the Rules of the Supreme Court are still officially "new" (CPR1.1(1)), and they still generate plentiful litigation about procedural points which are irrelevant to the merits.)

Second, the reforms saw the extension to the Queen's Bench of ponderous Chancery procedures which, while perhaps justifiable in grand suits about landed estates, had a malign effect on common law litigation. By the Common Law Procedure Act 1854, the hallowed Chancery litigation tools of disclosure and interrogatories became available in the common law Courts for the first time. They were enthusiastically adopted by practitioners, and, within a short space of time, Queen's Bench cases routinely became bogged down in applications for disclosure, lists of documents by affidavit, applications for inspection of documents, the administration of interrogatories, and preparation and service of sworn answers. Each of these new interlocutory stages inevitably delayed the ultimate resolution of the case, and came at a cost to the parties which was frequently wholly disproportionate to any possible benefit.

Third, the common law approach to pleading was overhauled. Traditional rules were much criticised for their complexity and technicality, and the formalistic, not to say ritualistic, style of pleading at common law generated documents which were incomprehensible to lay people. The Common Law Procedure Act 1852 and the Pleading Rules of Trinity Term 1853 did away with some of the old formalities and with various obscure rules about the consequences of specific types of plea. The Rules of the Supreme Court were so drafted as to encourage a more modern, simpler style, by which the parties would state their cases plainly in everyday language, as was, in theory, the Chancery practice. But if the old rules were arcane, they did at least generally produce pleadings which were reasonably concise. They were also intelligible to the professional lawyers and Judges who had to actually deal with them, even if lay people could not understand them. The shift towards an ordinary-language approach saw a surge in rambling and incoherent documents of excessive length and complexity, reflecting the reality of Chancery practice. When the Rules of the Supreme Court were revised in 1883, the request for further and better particulars was introduced to mitigate the problem (an alternative remedy was for the recipient of an incomprehensible pleading to apply to strike it out). Its use rapidly became commonplace, adding yet a further interlocutory stage, with attendant costs, to most Queen's Bench cases. An informed estimate was that the costs of a Queen's Bench action increased by something in the order of 20% as a result of the reforms.

The Conservative Lord Cairns (top) and Liberal Lord Selborne served as Lord Chancellor in governments of different political persuasion, but they co-operated in steering the Judicature Acts through Parliament.

It was particularly unfortunate that the adverse effects of these developments were largely felt at the interlocutory stages of cases, because this was an aspect of litigation where the Queen's Bench was notoriously weak. The Court was widely condemned by lawyers and litigants for hopeless inconsistency, and for producing unpredictable outcomes which appeared to turn on the temperament (or even the mood on the day) of the individual decision maker. This was an inevitable consequence of the manner in which interlocutory business was handled. The Judges' Chambers Act 1867 allowed Masters to hear interlocutory applications at first instance. The Queen's Bench had a heavy caseload, and the same, or similar, questions about the meaning of a particular Rule or the exercise of a given discretion tended to come up again and again in interlocutory proceedings. But there was no system for developing common thinking among the Masters. Instead, each Master was left to form his own view on any given question, and apply it every time that question arose. This meant that different Masters decided similar questions in widely divergent ways. The theoretical remedy for first instance anarchy was that an appeal lay from the Master to a Queen's Bench Judge. In a functioning system, decisions of the Judges on appeal should have provided the Masters with solid guidance as to the correct approach to particular questions, leading to future consistency. But this did not happen in practice, because interlocutory appeals were handled in a comparatively casual way. They were heard in Chambers, rather than in open Court, with the consequence that decisions were not reported even if a formal judgment was delivered (and the Judges often did not deliver a formal judgment at all). A Master might well not know that his decision had been appealed at all, let alone what the result had been. The appeal process simply reproduced the defects of first instance decision making, with each Judge following his personal instincts, and no mechanism for developing any shared approach. Interlocutory hearings therefore became a form of lottery. In these circumstances, it was no surprise that appeals from Masters became the norm, as unsuccessful parties gambled on doing better before the Judge (and with the possibility of a yet further appeal after that),. This made obtaining a final decision on even routine procedural matters became excessively time-consuming and costly.

The reforms did not affect only interlocutory proceedings. The Common Law Procedure Act 1854 permitted parties in civil actions to elect for trial by Judge alone, dispensing with the jury. This option steadily gained in popularity, and jury trial in Queen's Bench civil cases gradually become less common in the latter part of the 19th Century. This hastened the end of Lord Mansfield's merchant juries. They had already been compromised by an increasing tendency among busy merchants to evade jury service (often with the collusion of Court officials). Special juries were effectively finished off by the Juries Act 1870, which relaxed the qualifications for service, so that special juries largely stopped being "special." As a result, it became commonplace for questions of fact in commercial cases to be decided by jurors or (depending on the mode of trial) Judges who were ignorant of the business context. Inexperienced jurors and Judges were particularly at risk of being misled by unscrupulous expert witnesses, whose evidence in commercial cases was "often a scandal to the administration of justice". The obvious risk of haphazard results when facts in specialist cases were decided by non-specialists encouraged commercial litigants to wonder whether arbitrators with business experience might be more reliable.

Lack of expertise could similarly be an issue when it came to questions of law. The Queen's Bench Judges were recruited from practitioners, and their professional experience reflected the Court's diverse workload. It was therefore routine for a commercial case to come before a Judge with a background in criminal law (and vice versa). This was not a new phenomenon. It would not have been particularly problematic before some specific areas of the common law started to become increasinlgy specialised during the 18th Century. Even after that, it was mitigated by the system of ruling on points of law in banc: when a particular point was argued before all of the Judges, there was a good chance that at least one of them would have relevant expertise.

Motions in banc survived the Judicature Acts, although they were now heard by Divisional Courts of only three Judges (and after 1876, usually just two). But they did not really fit with the reformed Court system. The Judicature Acts had created a new Court of Appeal, but the parallel survival of motions in banc meant that many decisions of Queen's Bench Judges were subject to two levels of review, increasing the time and cost involved in reaching a final verdict. This was exacerbated when the appellate jurisdiction of the House of Lords, which had been abolished in 1875, was reinstated by the Appellate Jurisdiction Act 1876. A triple-tier system of appeals was unpalatable, and the 1883 Rules of the Supreme Court and the Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1890 effectively converted motions in banc into appeals to the Court of Appeal, by-passing the Divisional Court. Now, if an ignorant first-instance Judge got the law wrong, a litigant's only remedy was to start again in the Court of Appeal. Judicial inexperience of the relevant law was not necessarily confined to the commercial context. But it was regarded as a particular problem there, because the law relating to insurance, carriage of goods, international sale, and commercial instruments was technical and highly specialised.

The ancient judicial powers of the House of Lords were abolished by the Judicature Acts, but revived in 1876. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Aside from these ill-effects of the reforms, the Queen's Bench's performance was impaired by self-inflicted failings. Judicial nostalgia for the practices of the old common law Courts led to excessive use of Divisional Courts, which undermined judicial productivity and slowed down the Court's throughput of cases. The Judicature Acts provided that business at first-instance in the Chancery and Probate, Divorce & Admiralty Divisions should generally be before a single Judge, as had been the practice in the Courts which they replaced, but permitted the Queen's Bench, Common Pleas, and Exchequer Divisions to employ Divisional Courts of three Judges for matters which their predecessors would have dealt with in banc. This was a compromise between those who believed that sittings in banc were inefficient and that first-instance Judges should always sit singly, as in the other two Divisions, and those who believed that a collegiate approach promoted a better quality of decision making. The common law Judges tended to sit in Divisional Courts at the slightest excuse (Lord Coleridge, as Chief Justice first of the Common Pleas and then of the Queen's Bench, was a particular enthusiast for the old ways). But the compromise did not work well. Divisional Courts were not a true substitute for sittings in banc, but they were a drain on resources which diverted first-instance Judges from other hearings. (This confounded the expectations of legislators, who had hoped that the reforms would eventually enable them to reduce the number of Judges, in the interests of national economy.) This was one area where attempts were made to remedy the Court's deficiencies: the Appellate Jurisdiction Act 1876 firmly discouraged the use of Divisional Courts, and reduced their default strength from three Judges to two.

High Court listing arrangements were another major problem, and a constant source of complaint. They were widely regarded as anarchic. Litigants and lawyers protested that the Court invariably gave inadequate notice of hearings, and then frequently adjourned them at the last minute. Two glaring examples were reported in the legal press in the same week in 1887. A case which had been stayed by the Court in June was listed for trial in November, without prior warning to the parties, and in spite of the facts that the stay had not been lifted and that there was no reason why it should be. Inevitably, the trial did not proceed, and everyone's time was wasted. Kekewich J tried to pretend that the parties were somehow responsible for the Court's obvious incompetence. (Kekewich was a notoriously bad and bad-tempered Judge: the story of counsel telling the Court of Appeal that Kekewich had been the trial Judge but that this was not the only ground for appeal is surely apocryphal, but it well illustrates the contempt in which he was held.)

Meanwhile, Mathew J, finding himself unexpectedly unoccupied, decided without warning to try a case which stood at the bottom of another Judge's list, and which no-one had expected to start until much later in the day. When the parties, their lawyers and witnesses were not ready to start immediately, Mathew threw a tantrum, childishly declaring that it would be a good thing if a few solicitors were sued for professional negligence. The legal press rightly retorted that it would be a better thing if the Judges did something about a listing system which meant that clients, solicitors, counsel, and witnesses never knew before 4.30 in the afternoon whether or not a case was likely to be heard (at an unspecified time) the next day. Hearings and trials which were rushed on at short notice or vacated at the last minute (or both) were particularly irksome for busy commercial litigants. The problems were not confined to the Queen's Bench (the Kekewich incident occurred in the Chancery Division). But they do appear to have been more chronic there than in Chancery or the Probate, Divorce & Admiralty (in fairness, the Queen's Bench had a much larger caseload than either of the other Divisions).

The King’s Bench sitting in banc in Westminster Hall around 1800. The later common law Judges were reluctant to abandon such traditional ways.