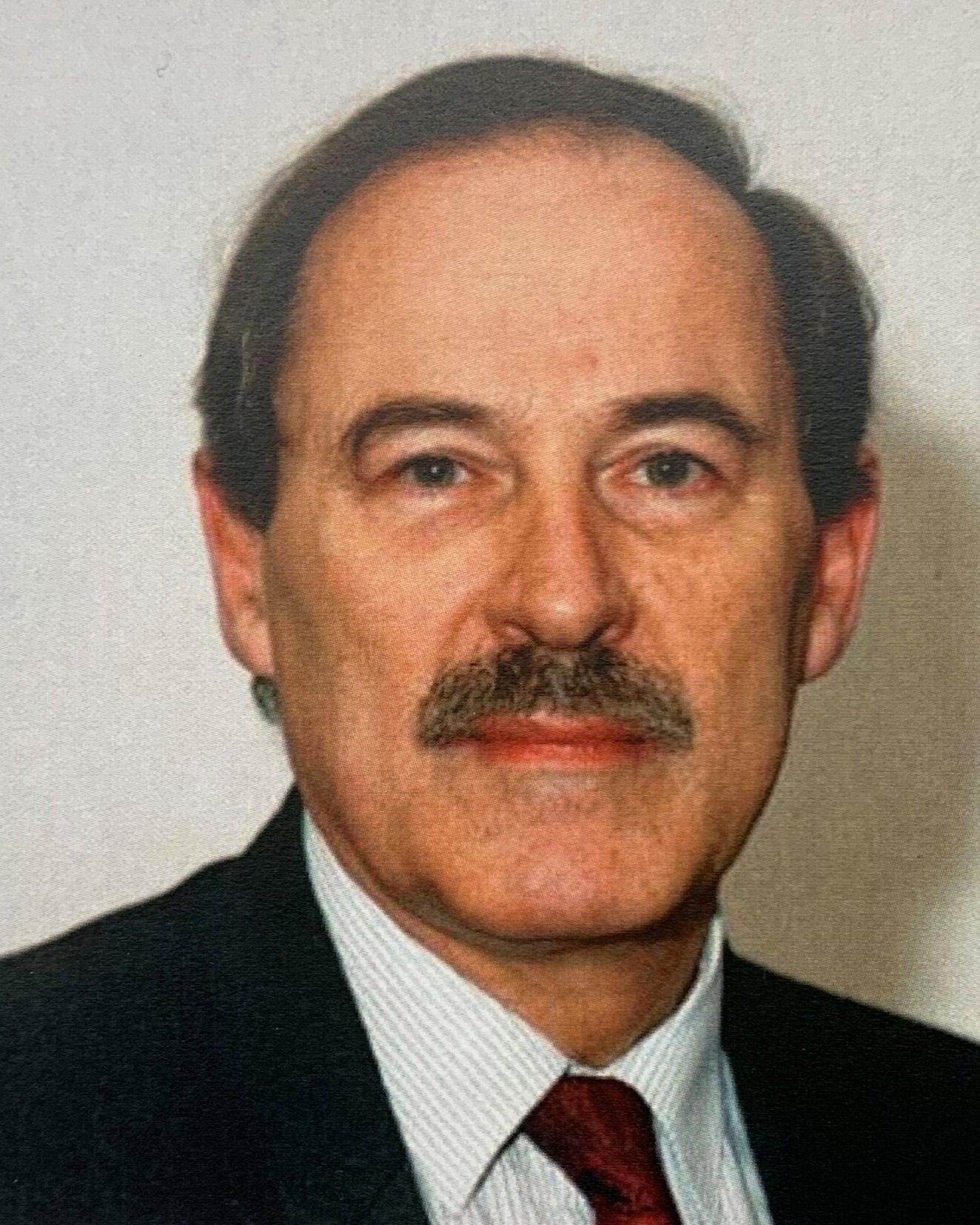

“A kind of Jurassic Park of judicial figures in the Commercial Court.”

Mr Justice Saville, at the time of the Commercial Court’s 100th Anniversary in 1995

Brief biographies of Commercial Judges

Compiling a definitive list of Commercial Court Judges is not as straightforward as might be expected (or, at least, as might be hoped). It is simple enough to establish which Judges have served in a particular Division of the High Court: all High Court Judges are assigned to a Division on their appointment, their appointments and assignments are officially announced, and lists of Judges by Division appear in the law reports. But, while the Commercial Court has formally been a “Court” since 1970, it has never been a Division, to which Judges are assigned as part of their terms of office. The Commercial Bench has always been drawn from the ranks of the existing King’s Bench (or Queen’s Bench) Judges, and the nomination of a Judge to sit in the Court has not always been marked by any official statement. The judicial lists in the law reports do not identify the Commercial Judges, and nothing in the nature of an official public record of Commercial Judges since 1895 exists.

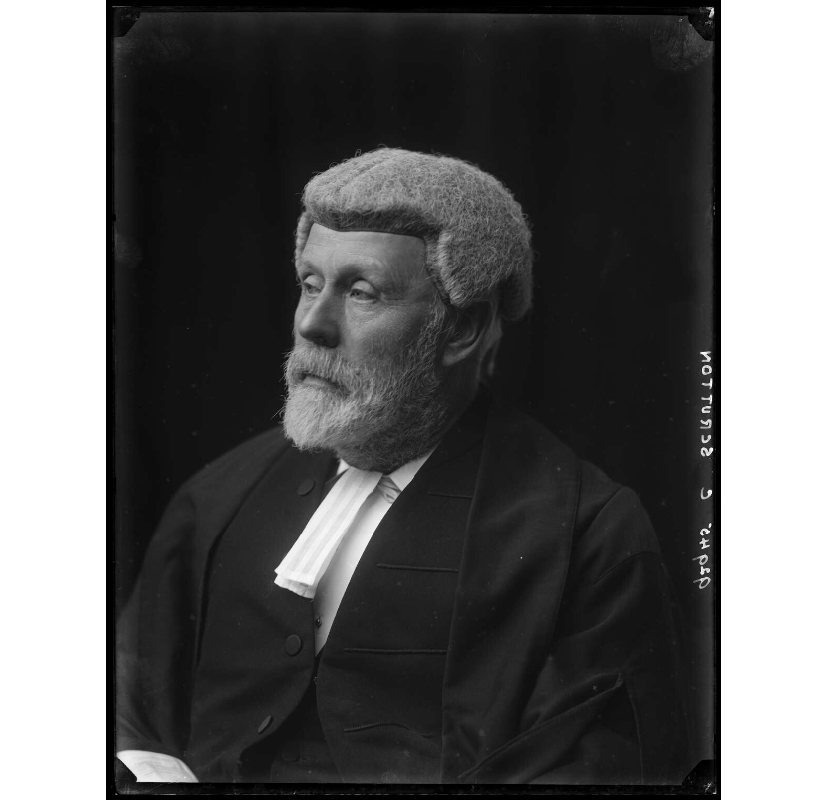

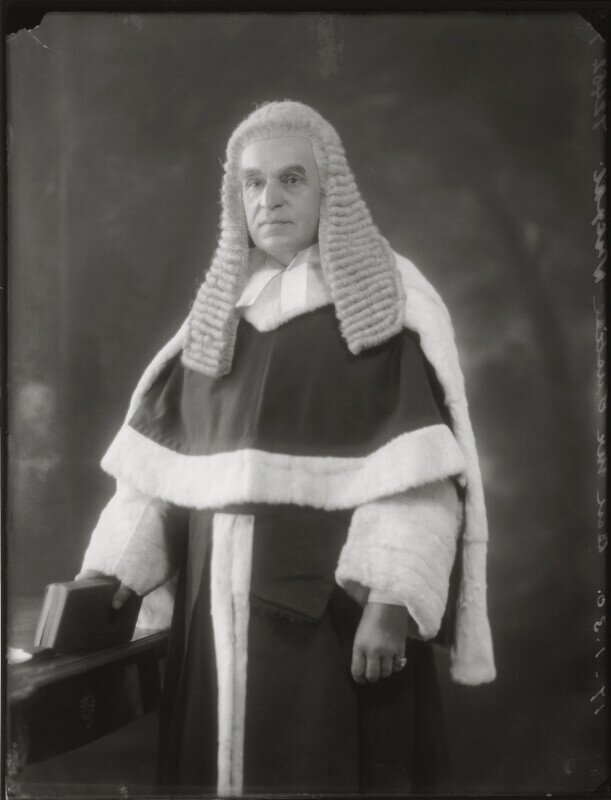

Since the Administration of Justice Act 1970, Judges have been nominated to sit in the Court by the Lord Chief Justice of the day. Consistently with the Court’s founding principle that commercial cases should be dealt with by specialist Judges with commercial expertise, they have been selected on the basis of their experience of commercial law and litigation while they were in legal practice. There is little difficulty identifying the Commercial Judges since (and for some time before) the Act. But things were rather less formal in the Court’s earlier days. The first three Commercial Judges, James Charles Mathew, Charles Arthur Russell, and Richard Henn Collins, were selected by popular acclaim at meetings of the Queen’s Bench judiciary. Within a few years after 1895, there existed a “rota” system, by which selected Judges took it in turn to run the Court. But the process by which Judges were appointed to the rota is not transparent. Some, such as John Bigham, Joseph Walton, and William Pickford, had been outstanding commercial practitioners before elevation to the Bench, and were obvious candidates. Others, Gainsford Bruce, Reginald Bray, and Arthur Channell, for example, were less predictable, although they each had at least some commercial experience. But whatever the respective merits of any of these Judges, it is not clear by what process they were selected to sit in the Commercial Court, or who was responsible for the selection.

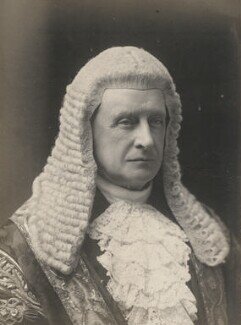

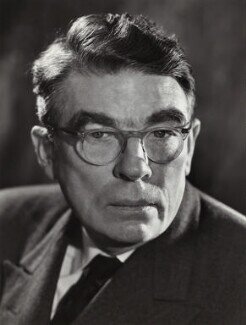

The first Commercial Judge, Sir James Charles Mathew

And, however the rota system was organised, it did not survive long. In 1917, the 8th edition of ‘Scrutton On Charterparties’ stated that the rota “seems to have disappeared”. Scrutton does not appear to have known how or when that had happened, although he had been a Commercial Judge himself for seven years by 1917. Scrutton suggested that the discontinuance of the rota meant that all of the King’s Bench Judges were now available to sit in the Commercial Court. But this was a purely theoretical position, since there has never been an era in which all of the Division’s Judges could be found hearing cases about bills of lading, charterparties, and marine insurance. There must have been some residual selection process in Scrutton’s day and in the years between then and 1970. But its nature is unclear.

In very many cases, of course, no official proof is required in order to establish that a particular individual served as a Commercial Judge: Scrutton himself is an obvious example. For less prominent judicial figures, items and notices in the legal press sometimes provide evidence. Edward Acton is little remembered today. But The Law Times for June 1929 and for February 1933 records that he was twice (at least) the Judge in charge of the Commercial Court. The law reports also contain clues, and for many years they have expressly identified cases which were heard in the Commercial Court. But there were long periods during which even the specialist Lloyd’s Law Reports did not bother to state whether a case was heard in the Court or in the general Queen’s (or King’s) Bench List. Since it has never been compulsory for all cases of a commercial nature to be heard in the Commercial Court, the fact that a reported case relates to freight or demurrage, marine insurance, or time charters does not guarantee that it was allocated to the Commercial Court. But it is likely to be a very good indication; and, if a particular Judge recurrently crops up in the reports deciding such cases, it is reasonable to infer that he had been selected as a Commercial Judge. It seems fairly clear, for example, that Wilfrid Lewis sat in the Court during the 1940’s, although none of his shipping decisions reported in Lloyd’s are expressly identified as Commercial Court cases.

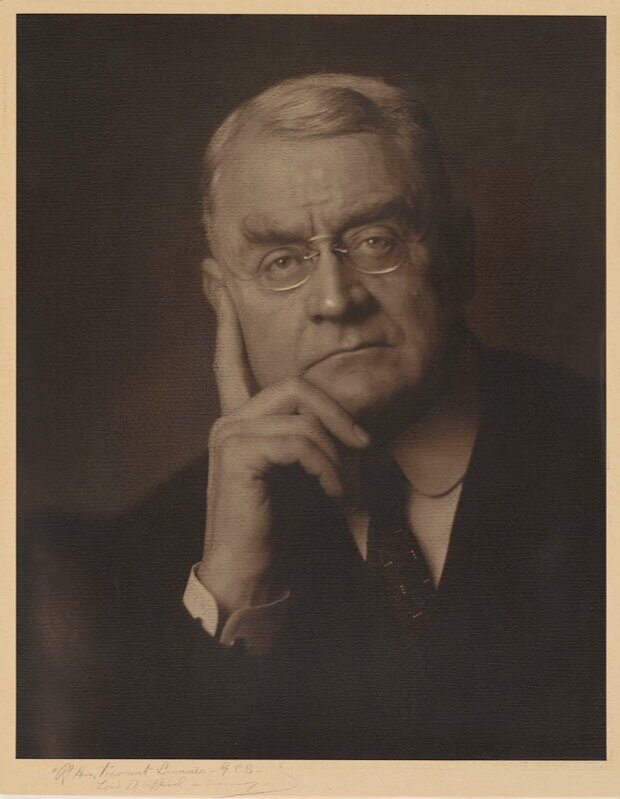

Not a Commercial Judge: Lord Denning did not become a Commercial Court regular as a first-instance Judge. However, during his long tenure in the Court of Appeal, he tended to identify as a commercial lawyer for the purposes of the convention that panels for commercial appeals should include at least one specialist. Commercial practitioners and litigants did not always agree with this self-characterisation.

Some omissions which may seem surprising are a consequence of shifts in judicial business and changes to the Court system. Today, the Admiralty Judge is selected from the Commercial Judges, and usually spends more time in the Commercial Court than in trying collision claims or limitation actions in the Admiralty. But the Admiralty was not part of the Queen’s (or King’s) Bench Division at all until 1970 (it was a constituent of the separate Probate, Divorce & Admiralty Division), and, for two decades after that, there was usually sufficient Admiralty work to keep a Judge fully occupied (and sometimes to require reinforcements from the Commercial Court). As a result of these factors, such eminent shipping Judges as John Gorell Barnes, Maurice Hill, Alfred Bucknill, Gordon Willmer, and Barry Sheen sat in the Commercial Court either not at all or on only one or two occasions.

There are marginal characters. Horace Avory was the Judge in three reported Commercial Court cases. But one of them settled before the plaintiff’s counsel (Theo Mathew, son of the first Commercial Judge) began his opening speech; and Avory’s brief judgments in the other two hardly seem to justify ranking him among the Commercial Judges. (Avory was fundamentally a criminal specialist, although he did sit on a number of commercial arbitration appeals, as a member of two- or three-Judge Divisional Courts.) Similarly, Gordon Slynn, who became the United Kingdom Judge at the European Court, and later a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary, was the Judge in two relatively short reported Commercial Court cases. But his reputation as a European lawyer is so entrenched that to categorise him as a Commercial Judge would seem incongruous.

The occasional Judge who heard only a single reported Commercial Court case does not make the list, even though that means excluding the most famous of all English Judges, Alfred Thompson Denning. (Pinch & Simpson v Harrison, Whitfield & Co (1948) 81 Lloyd’s Rep 268: not explicitly reported as a Commercial Court case, but, from its subject matter, very likely to have been one.)

There appears to have been a convention down to the 1940’s that the Lord Chief Justice of the day, as head of Division, should sit in the Commercial Court from time to time. But it would hardly be appropriate to count such essentially political figures as Gordon Hewart and Thomas Inskip as Commercial Judges on that basis. (Inskip did some Prize work at the Bar, and made a fair number of appearances in the Admiralty, but never approached being a commercial specialist. Hewart’s only appearances in commercial litigation were in his capacity as Law Officer, and his legion of critics would contend that he scarcely deserves to be called a Judge at all.) Richard Webster and Rufus Isaacs, whose practices at the Bar did extend to commercial work, could make better claims. But, for consistency, they too are omitted.

(Tentative List 0f) The Judges Of The Commercial Court