Respected, capable, but unspectactular, both at the commercial Bar and on the Bench, William Lennox McNair had the misfortune to be overshadowed for most of his career by a brother who became one of the outstanding figures of public international law and by more stellar Commercial Judges.

Born in London in 1892, “Willie”, as he always known, was the fourth and youngest son of John McNair and his wife Jeannie (formerly Jean Ballantyne). John and Jeannie were both originally from Paisley, future scene of the events in Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562. John's family were in the weaving trade, and Jeannie had been a teacher. After the move to London, John made a relatively modest living as a Lloyd's underwriter.

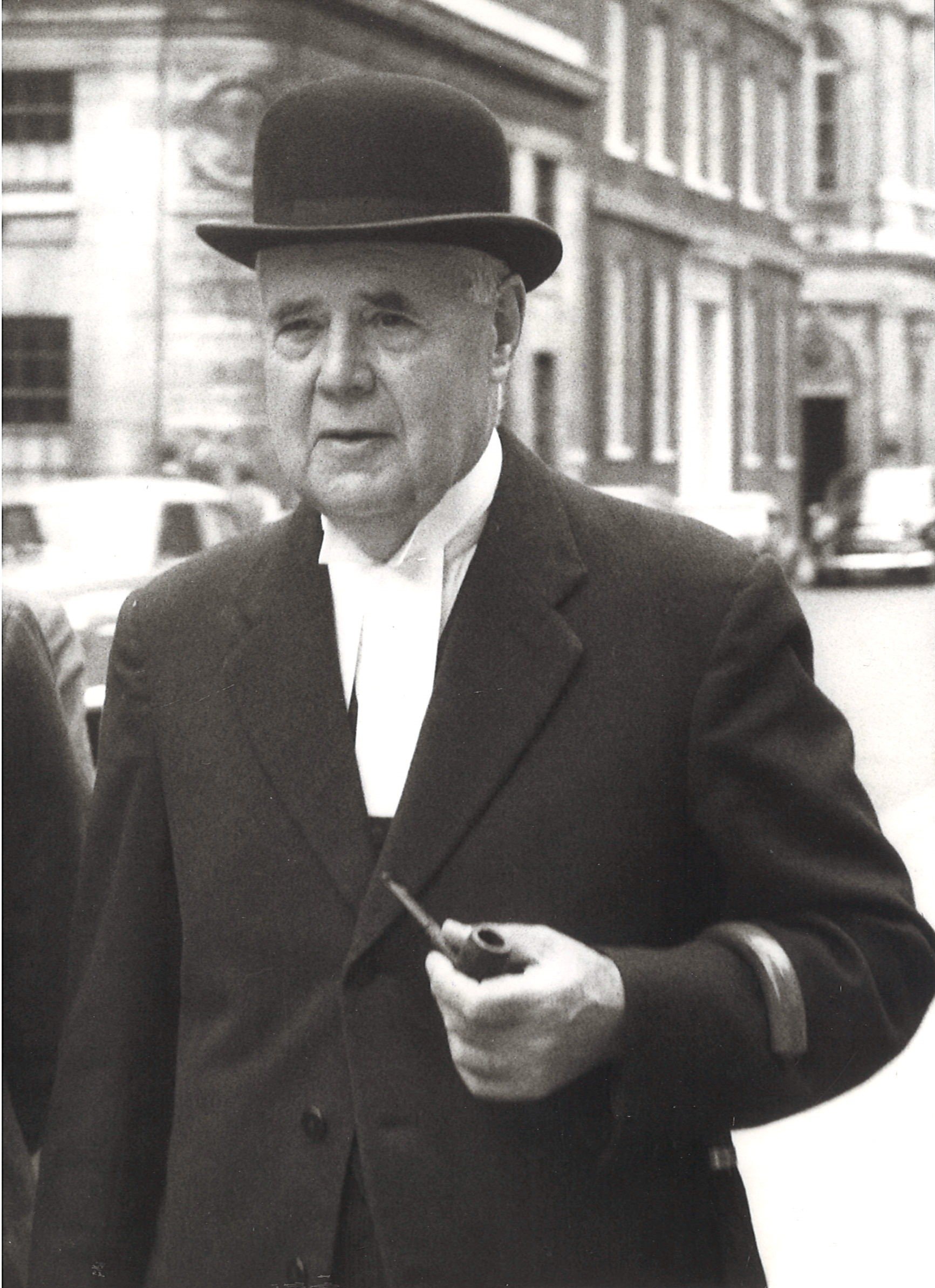

William Lennox McNair in 1964.

McNair went to public school on a scholarship, then studied law at Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge. In his choice of both College and subject, he followed his eldest brother, Arnold. Arnold had left school at seventeen to work for an uncle who was a London solicitor, had studied law at Caius in his twenties, and, after a brief second stint in private practice, had returned to the College as an academic. In a long life, Arnold married Clement Bailhache's daughter Marjorie, wrote well-received books and articles on a range of legal subjects, occupied Chairs in international law and comparative law at Cambridge and London, became a Judge and then President of the International Court of Justice, and was the first President of the International Court of Human Rights. William, meanwhile, completed his degree (with first class honours) in the summer of 1914, on the eve of the Great War. He served in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment from 1914-1918, reaching the rank of Captain, participating in the fighting at Gallipoli (where he was wounded), and earning a mention in despatches. Apparently already decided on his future career, he was called to by Bar by Gray’s Inn during 1917, while still on active service.

After demobilisation, McNair returned to Caius for post-graduate study. He was President of the Cambridge Union in 1919, immediately before John Morris. During this second spell at Cambridge, McNair won an award in international law, which would become Arnold's specialist subject. But William chose to make his name in a different area. Called to the Bar by Gray's Inn, he set about establishing himself as a commercial practitioner. He appears to have started out in a solicitors' office, for the affidavit evidence in Graham v Motor Union [1922] 1 KB 562 (a marine insurance claim following the total loss of the ship in circumstances which the insurers considered highly suspicious) records that the insurers' solicitors had sent "a representative, Mr W.L. McNair", to interview the crew in Spain. But at the beginning of the 1920's, McNair joined 3 Essex Court, an established barristers' chambers in the Temple.

The immediate post-War period was a good time for a young barrister looking to build a career in the field, for there was a surge in commercial litigation in the first few years after 1918. Much of the work found its way to 3 Essex Court, which had been a "knock about" general common law chambers before the Great War, but turned itself into a leading commercial set during the 1920's and 1930's. McNair was at the forefront of this transformation, finding work at once, making regular appearances as junior counsel in reported insurance, sale of goods, and shipping cases, and being led by prominent Commercial Court practitioners including Robert Wright, Frank MacKinnon, and D.C. Leck. Wright was his leader in Samuel v Dumas [1924] AC 431, another suspicious sinking case, which decided that the scuttling of a ship by the crew was not a loss by "perils of the sea" within a marine insurance policy. This was not easy to square with previous authority, and former Commercial Judge Lord Sumner delivered a lengthy dissent. But even Sumner was impressed by McNair's contribution to the oral argument before the Lords, commenting that he had "put the points freshly". Given that Sumner was not much prone to judicial compliments, this was praise indeed for someone so junior. McNair was back in the Lords in Brightman v Bunge y Born [1925] AC 799, an appeal about the scope of a laytime exceptions clause (though the Court of Appeal decision is better-remembered today as a leading authority on the distinction between "contract options" and "performance options").

McNair's professional profile was boosted by his editorship of two leading shipping law textbooks. In 1922, he joined solicitor Robert Temperley as junior editor of Temperley's 'Merchant Shipping Acts', well-established as the leading work on the subject. Even more prestigiously, in 1925 he and Samuel Porter inherited 'Scrutton on Charterparties' from T.E. Scrutton and Frank MacKinnon, who retired as editors because of Scrutton's conscientious objection to the Carriage of Goods by Sea Act 1924. Porter and McNair edited the 12th and 13th editions of 'Scrutton' together, after which McNair became the senior editor until the 17th edition in 1964. McNair's working partnership with Porter extended to the courtroom, with Porter leading him in a succesion of commercial cases from the mid-1920's onwards. Although the post-War commercial litigation boom levelled off after a few years, McNair remained busy, and his name continued to feature regularly in reported cases through the 'twenties. He took leave of absence from private practice around the turn of the decade for government work in the Parliamentary Counsel's Office. But this was a short break. McNair was back in the law reports by 1931, and, by the mid-1930's, he was joint head of 3 Essex Court with Henry Willink (though McNair's was the name on the lease of the building). In the years before the Second World War, future Commercial Judges John Megaw, Alan Mocatta, and Eustace Roskill all joined the set, reinforcing its pre-eminent reputation for commercial work.

To judge from the law reports, McNair's own busy practice was exclusively commercial, and entirely London-based. For all of his success, however, McNair was slow to move up to the next level of his profession: while Willink was appointed King's Counsel in 1935 (alongside McNair's near-contemporaries and future Commercial Court Judges John Morris and Frederic Sellers), McNair was still a junior at the outbreak of the Second World War.

Too old to fight again, McNair spent most of the War years in government service on the Home Front. As Legal Adviser to the Ministry of War Transport from 1940-1941, he dealt with legal issues relating to the requisitioning of ships, the standard forms of wartime chartperparty by which merchant vessels were taken up into government service, and the legal status of British cargo ships trapped in foreign ports. He worked closely with his junior Chambers colleague Eustace Roskill, who had been John Morris's pupil before joining 3 Essex Court. McNair was made a Knight Bachelor in the 1946 New Year's Honours in recognition of his war work, making him the only Commercial Court Judge to be knighted in his own right before joining the Bench. (Walter Phillimore was already “Sir Walter” on his appointment in 1897, but that was in right of the Baronetcy which he had inherited from his father, Admiralty Judge Robert Phillimore.)

Members of the Llandow inquiry team at the crash site: McNair on the far right.

McNair finally became King's Counsel in 1943, in the first round of appointments since 1939. In 1945, he left the civil service to resume private practice and launch himself as a new KC at the relatively advanced age of fifty-three. He returned to a Temple which had suffered substantial damage from the Luftwaffe. (The building - forming part of Brick Court - directly opposite 3 Essex Court had been bombed out. It was demolished, and the site is now a car park.) The Benchers of the Inns proposed to redistribute the surviving accommodation among the flow of barristers gradually returning to practice. But their plan to forfeit the lease of 3 Essex was forestalled by the fact that McNair been paying the rent punctually since 1939, although the set had shut down for the duration of hostilities. Henry Willink, who had become an MP in 1940 and was the wartime Minister of Health, returned to practice rather fitfully after the War. He gave up altogether when he was appointed Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge, in 1948, leaving McNair as sole head of chambers.

McNair's career as a commercial leader was short and coincided with a decline in commercial litigation, but he argued more than half-a-dozen cases before the House of Lords and Privy Council. They included The 'Unitas' [1950] AC 536, one of the last Prize cases in English law; the mysterious The 'Greystoke Castle' [1947] AC 265, notionally a case about general average, but in which the Lords appeared to subvert the rule against recovery of pure economic loss in negligence; and Comptoir D’Achat v Ridder [1949] AC 293, in which McNair convinced the Lords that labels such as “CIF” and “FOB” do not always determine the substance of a contract. He also recruited future Commercial Judges John Donaldson and Michael Kerr to 3 Essex Court, which now stood alone as the leading commercial set, after several of its former rivals failed to make a comeback in 1945.

The international juristic success of Lord Arnold McNair overshadowed the domestic career of his younger brother.

In 1948, McNair chaired an inquiry into a collision above RAF Northolt between a Scandinavian Air Services air liner and an RAF plane, in which thirty-nine people were killed. Two years later, he was appointed to head the investigation into the Llandow crash, in which a plane flying Welsh rugby fans home from a Five Nations match against Ireland crashed on landing. Eighty passengers died, the highest number in any plane crash to that date. The inquiry concluded that mistakes in the loading of the passengers' luggage had made the plane badly unbalanced as it approached the runway. By the time the inquiry published its report, in November 1950, McNair's appointment as a King's Bench Judge had been announced. He replaced former star of the criminal Bar Norman Birkett, who had been one of the British Judges at the Nuremburg Trials, and who was moving up to the Court of Appeal after nine years in the King's Bench. The 'Solicitors' Journal' sympathised that it was McNair’s fate to be left "toiling in the tax-ridden penury of the King's Bench" while his brother Arnold luxuriated in a tax-free salary on "the Elysian Fields of international jurisprudence". (William did not fully embrace his brother's internationalist outlook. Future Commercial Judge Michael Kerr, who had got to know the elder McNair while studying at Cambridge, arranged pupillage in 3 Essex Court on the strength of Arnold's assurance that the life of a shipping barrister was packed with glamorous foreign travel. He later discovered that, aside from holidays in his ancestral Scotland, William had barely left England in his life: that trip to Spain in Graham v Motor Union must have been an exception to the rule.)

The relatively low pay was not the only challenge of McNair's new role. The 1950's were the quietest years in the Commercial Court's history, and the workload reached such a low level that questions were raised about the Court's future. In these conditions, McNair found himself dealing with disputes far beyond the commercial boundaries of his practice at the Bar. His first reported cases were in the Court of Criminal Appeal, and he was soon sitting in trials about employment, landlord and tenant, local government, personal injury, and even defamation. Even a fair number of his cases in Lloyd's Law Reports (which reported more than a hundred of his judgments) involved crew members falling into ships' holds or stevedores tripping over objects on docksides rather than disputes about commercial transactions. The volume of commercial work began to pick up as the 'fifties turned into the 'sixties. But crime, personal injury, and industrial accidents account for a greater proportion of McNair's reported judgments than bills of lading, charterparties, and insurance.

One of his most high-profile cases (at least so far as the general public was concerned) was the 1958 trial of the Costa Brava Wine Co Ltd at the Old Bailey, on criminal charges of falsely describing a sparkling Iberian wine as "Spanish Champagne". The case was brought on the basis that "champagne" had a settled meaning which was confined to sparkling white wine from North-East France. It was a private prosecution, pursued by elements of the wine trade which dealt in altogether more expensive products than Costa Brava's Spanish fizz. The litigation looked like an attempt by the old order to force a new entrant out of the market, and it attracted public attention. For a week, newspaper readers were entertained by evidence about the "hunt-ball clientele" of high-class wine merchants, the "snob value" of "proper" champagne, and the relative merits of the French and Spanish wine industries. The jury accepted Costa Brava's defence that "champagne" was a generic label for sparkling white wine (there were no EU Protected Designation of Origin rules in those days), and the case ended in an acquittal.

McNair also hit the headlines as a member (alongside Mr Justice Gorman) of the Election Court which tried the Stansgate Peerage Case. In 1961, a petition was presented to the Court for the ejection from his seat in the Commons of the Labour MP for Bristol South East. The grounds for the action were that the MP in question had become the 2nd Viscount Stansgate on the death of his father (who had also been a Labour MP), and, that, as a Peer of the Realm, he was now legally disqualified from sitting in the Commons. Viscount Stansgate - who preferred to be known as Mr Anthony Wedgwood Benn - protested that he did not want to be and had never wanted to be a Peer, and that he would rather stay in the Commons than transfer to the House of Lords. It was to no avail. McNair and Gorman ruled that the heir to a peerage had no legal right to disclaim the succession, and Benn was exiled from the Commons for two years, until the law was changed and he got back in at a bye-election.

Much closer to McNair's own shipping law background were The 'Vancouver Strikes Cases' [1960] 1 QB 439, a clutch of voyage charter demurrage and dispatch claims and counterclaims arising out of a strike by Canadian grain elevator operators. Raising a few apparently short and self-contained points of construction, the ‘Strikes Cases’ occupied sixteen days in the Court of Appeal, nine days in the House of Lords, and a full five Commercial Court weeks before McNair. McNair was upheld in the Court of Appeal, but partly overruled in the Lords, where Viscount Radcliffe hailed his fifty-page judgment, in a rather qualified compliment, as "massive and luminous".

McNair was also the trial Judge in the great Hague Rules cases of Renton v Palmyra [1957] AC 149 and The 'Muncaster Castle' [1961] AC 807, which established, respectively, that the Rules do not prevent the parties from making their own agreement about responsibility for cargo operations, and that the shipowners' duty of diligence to make the vessel seaworthy is non-delegable. On both occasions, however, the final outcome in the Lords differed from McNair's decision at first-instance. In fact, McNair ended up with rather a poor record in prominent commercial cases; he was overruled again in The 'Heron II' [1969 1 AC 350, the leading authority on remoteness of damages in contract.

McNair at around the time of the Stansgate/Benn election case.

More favourably received was the judgment in the McNair case which is probably best known to modern lawyers. In Bolam v Friern Hospital [1957] 1 WLR 582, McNair held that a doctor was not negligent if he followed a course endorsed by a responsible body of professional opinion, even if some other professionals took a different view. The 'Bolam Test' was later extended to other fields of professional liability, and is still often cited today.

When Lord Justice Norman Birkett announced his retirement at the end of 1956, some people thought that McNair would once again follow in Birkett’s path up the judicial career ladder. The 'Telegraph' confidently predicted that Birkett’s replaement would be either McNair or fellow Commercial Judge Colin Pearson. The paper’s correspondent somehow managed to overlook the more compelling case for a third member of the Commercial Court, Frederic Sellers. Sellers duly got the job, and McNair never was promoted, staying at first-instance until he retired in 1966. On his last day, Commercial Court colleagues John Megaw, Alan Mocatta, and Eustace Roskill sat beside him on the Bench while future Commercial Judge John Donaldson QC paid tribute to "the great work which he had done for the Court and commercial law in England". Unmarried, McNair lived quietly in retirement with his younger sister Dorothy, a pioneer woman medical specialist, who had started out in obstetrics before later becoming an anaesthetist. Willie and Dorothy split their time between their home in Dulwich and their parents’ homeland, Scotland, where they indulged a shared love of fishing.

McNair’s judicial career had been unfortunately mis-timed. It coincided not only with a slump in commercial litigation, but also with the first-instance tenures of Patrick Devlin and Kenneth Diplock, younger and more obviously gifted Commercial Judges. Under different circumstances, McNair might have made a greater impression as a jurist. As it was, his reputation was eclipsed by that of his eldest brother. Arnold was made a life peer, showered with awards and honours, and died garlanded with praise by the press. Willie's death in 1979 was largely ignored by the newspapers, and he has no 'Dictionary of National Biography' entry. But Gonville & Caius College, which made him an Honorary Fellow in 1951, still awards Sir William McNair Prizes In Law.