Compiling a definitive list of Commercial Court Judges is not as straightforward as might be expected (or, at least, not as straightforward as might be hoped). In fact, it may be impossible, at a distance of more than a century and a quarter, to identify with certainty all of the Judges who have sat in the Court.

From a modern perspective, this is perplexing. It is a part of the standard form of today’s judgments to name the Court, and law reports routinely record that a decision was given in the Commercial Court. This information alone makes it easy to keep track of the Court’s personnel from time to time. And whenever a new Judge is nominated to sit in the Court by the Chief Justice of the day, under the Administration of Justice Act 1970, the fact is made public.

Click on the button for a (tentative) list of Commercial Court Judges since 1895

But things have not always been so transparent. The law reports have long included information showing which Judges are assigned to which Division of the High Court. But the Commercial Court was created as a specialist list within the Queen’s Bench Division, not as a Division in its own right: and, although it has formally been a “Court” since 1970, it has retained its status a sub-division of the Queen’s or King’s Bench. The judicial lists in the law reports do not identify the Commercial Judges, and nothing in the nature of an official public record of Commercial Judges since 1895 exists.

In its early days, the Court operated on a “rota” system. Periodically, a number of Queen’s Bench Judges with particular expertise in commercial litigation were selected to take turns dealing with Commercial Court cases. It is not clear precisely how the selection process worked. Some Judges - Joseph Walton, John Bigham - had been commercial specialists at the Bar, and were obvious candidates. Others - Reginald Bray - were from a more generalist background, albeit with at least some commercial experience. But, however the system was organised, it is usually possible to identify the Commercial Judges relatively easily for this early period. Thus, the very first rota Judges - James Charles Mathew, Charles Arthur Russell, and Richard Henn Collins - were publicly named when the Court was created by the Notice as to Commercial Causes in 1895, and changes to the rota were regularly reported in the legal press.

Even for this period, however, there are doubtful cases: for example, T.E. Scrutton, who was one of the early Court’s most prominent practitioners, and later one of its most eminent Judges, was not quite certain whether or not Gainsford Bruce qualified as a “real” Commercial Judge. And the rota system did not survive long. In 1917, the 8th edition of ‘Scrutton On Charterparties’ stated that the rota “seems to have disappeared”, and Scrutton does not appear to have been quite clear as to what had replaced it.

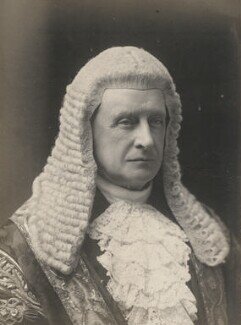

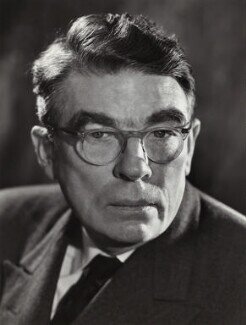

The first Commercial Judge, Sir James Charles Mathew

In very many cases, of course, no official proof is required in order to establish that a particular individual served as a Commercial Judge: Scrutton himself is an obvious example. For less prominent judicial figures, items and notices in the legal press sometimes provide evidence. Edward Acton is little remembered today. But The Law Times for June 1929 and for February 1933 records that he was twice (at least) the Judge in charge of the Commercial Court. The law reports also contain clues. For many years, the specialist Lloyd’s Law Reports have expressly identified cases which were heard in the Commercial Court. But there was a relatively long period during which even Lloyd’s did not bother to provide this information. And it coincided with a time in which several King’s Bench Judges with no very obvious commercial expertise - John Darling, Alfred Lawrence, Montague Sherman - decided a fair number of charterparty, bill of lading, and sale of goods cases.

The upshot is that, for a period from around the Great War to the 1960's, there are doubtful instances where it is not clear whether a Judge who decided an obviously commercial case was an official nominated Judge of the Commercial Court or dealt with the case on some other basis: eg, because, for some reason, the case had never been transferred to the Commercial Court, and was left languishing in the “general list”.

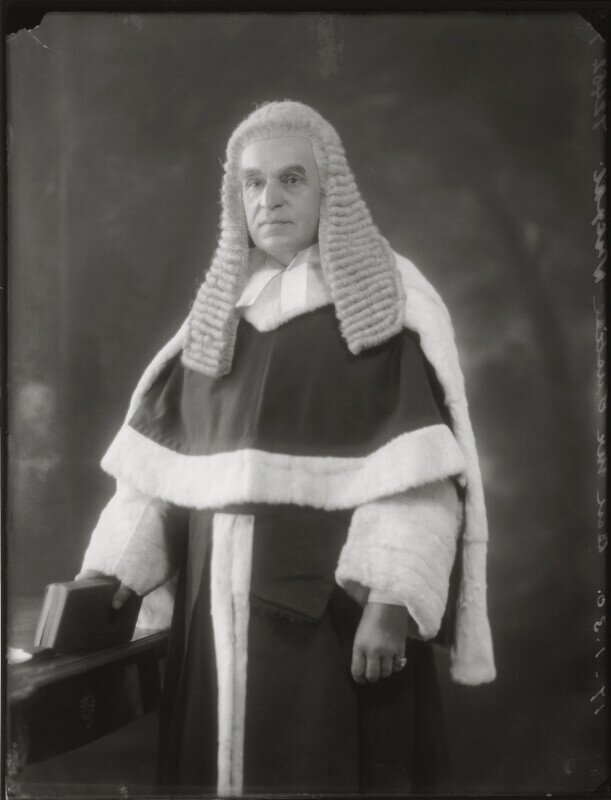

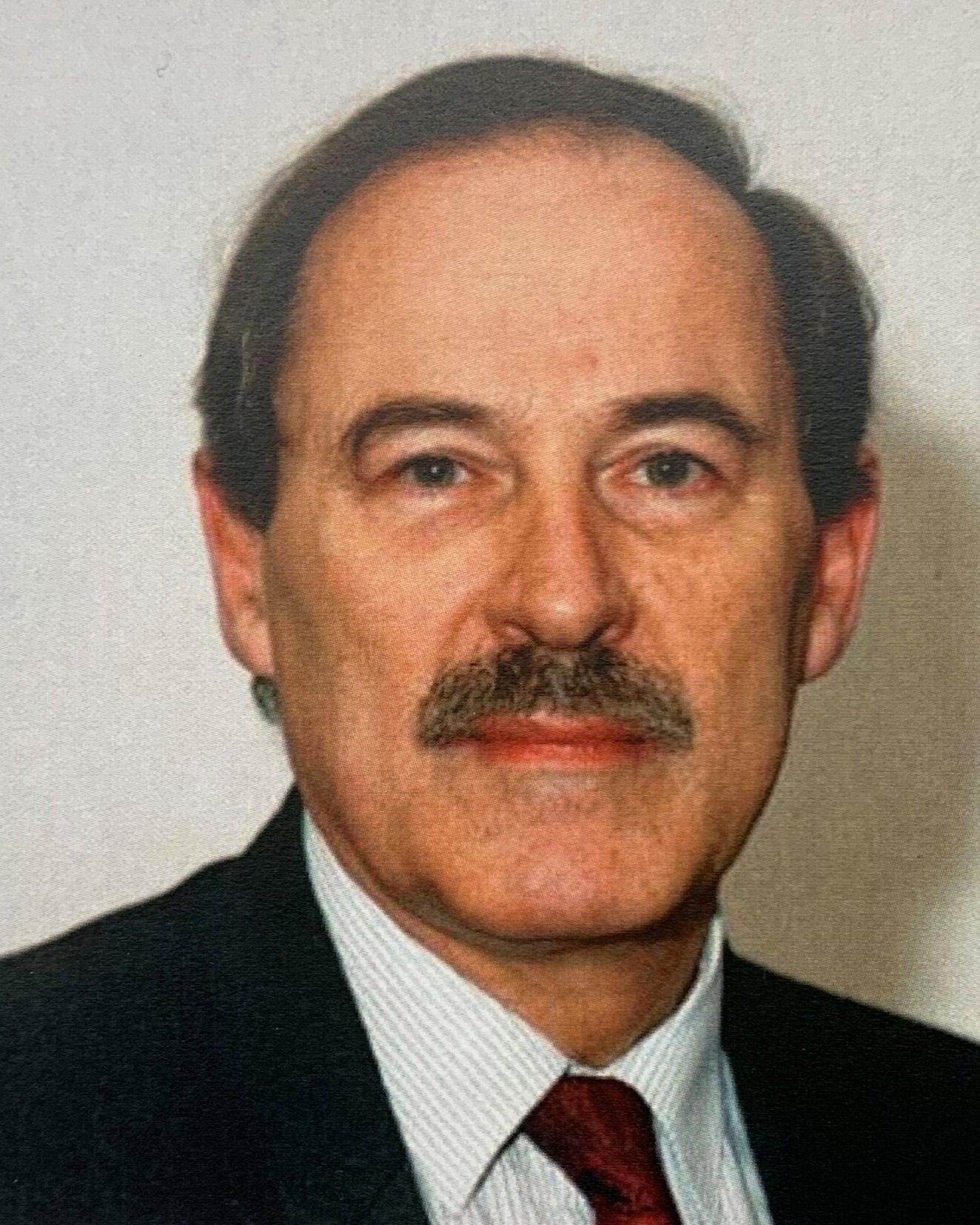

Not a Commercial Judge: Lord Denning did not become a Commercial Court regular as a first-instance Judge. However, during his long tenure in the Court of Appeal, he tended to identify as a commercial lawyer for the purposes of the convention that panels for commercial appeals should include at least one specialist. Commercial practitioners and litigants did not always agree with this self-characterisation.

The approach which has been adopted here leans towards inclusivity: any Judge who decided several cases of an obviously commercial nature within a relatively short period of time is assumed to have been a Commercial Judge. This means that Bruce, Darling, Lawrence and Shearman are all included, even if they were not remotely Commercial Judges in the same sense that Sumner, Scrutton, Devlin, and Goff were.

Inevitably, there are marginal characters. Horace Avory was the Judge in three cases which are reported as having been listed in the Commercial Court. But one of them settled before the plaintiff’s counsel (Theo Mathew, son of the first Commercial Judge) began his opening speech; and Avory’s brief judgments in the other two hardly seem to justify ranking him among the Commercial Judges. (Avory was fundamentally a criminal specialist, although he did sit on a number of commercial arbitration appeals, as a member of two- or three-Judge Divisional Courts.) Similarly, Gordon Slynn, who became the United Kingdom Judge at the European Court, and later a Lord of Appeal in Ordinary, was the Judge in two relatively short reported Commercial Court cases. But his reputation as a European lawyer is so entrenched that to categorise him as a Commercial Judge would seem incongruo

The occasional Judge who heard only a single reported Commercial Court case does not make the list, even though that means excluding the most famous of all English Judges, Alfred Thompson Denning. (Pinch & Simpson v Harrison, Whitfield & Co (1948) 81 Lloyd’s Rep 268: not explicitly reported as a Commercial Court case, but, from its subject matter, very likely to have been one.)

Two categories merit specific mention.

First, some omissions which may seem surprising are a consequence of shifts in judicial business and changes to the Court system. Today, the Admiralty Judge is selected from the Commercial Judges, and usually spends more time in the Commercial Court than in trying collision claims or limitation actions in the Admiralty. But the Admiralty was not part of the Queen’s (or King’s) Bench Division at all until 1970: it was a constituent of the separate Probate, Divorce & Admiralty Division. And, for two decades after the Admiralty was merged into the Queen’s Bench, there was usually sufficient specialist business to keep the Admiralty Judge fully occupied (and sometimes even to require reinforcements from the Commercial Court). As a result of these factors, such eminent shipping Judges as John Gorell Barnes, Maurice Hill, Alfred Bucknill, Gordon Willmer, and Barry Sheen sat in the Commercial Court either not at all or on only one or two occasions. They do not make the list.

Second, there appears to have been a convention down to the 1940’s that the Lord Chief Justice of the day, as head of Division, should sit in the Commercial Court from time to time. Lord Alverstone, Viscount Reading, Lord Hewart, and Viscount Caldecote all did so. Perhaps they believed that they were following a tradition established by Charles Russell, who was Chief Justice when the Commercial Court was established in 1895. But the right of Russell, who was not only instrumental in establishing the Court, but was also one of the first rota Judges, to be regarded as a Commercial Court Judge, is beyond question. It seems less appropriate to count such essentially political figures as Alverstone, Reading, Hewart, and Caldecote. Alverston and Reading did undertake some commercial work at the Bar, when the demands of their parliamentary careers allowed them to practice at all. But, for the sake of consistency, all four are omitted.