Thomas Richard Atkin Morison ("Tom" to family, friends, and colleagues) had the distinction, unique among members of the Commercial Bench, of being named after judicial ancestors on both sides of his family. "Thomas" was his paternal grandfather, Lord Morison, who had been a Senator of the College of Justice in Scotland. Even more distinguished, "Richard Atkin" was none other than "Dick" Atkin, Lord Atkin of Aberdovey, who was a Judge for thirty years, sixteen of them as a Law Lord, who founded the modern law of negligence in the snail-in-the-ginger-beer-bottle case of Donoghue v Stevenson, and who was Morison's grandfather on his mother's side. It would have been unrealistic and unkind to have expected Morison to equal his maternal grandfather's exalted status as one of the most highly-regarded of all English law jurists. But Morison did obtain the satisfaction of matching Atkin's achievement in becoming a Commercial Court Judge.

Tom Morison was born in early 1939, during the period of relative calm between the Munich Agreement and the outbreak of the Second World War. His father, Harold, who served with the Scots Guards during that conflict, was the son of prominent Edinburgh advocate Thomas Morison and his first wife, Isabel. A politician as well as a lawyer, Thomas Morison sat as a Liberal MP for Inverness, and was successively Solicitor-General for Scotland (1913 to 1922) and Lord Advocate (1920 to 1922), before being elevated to the Scottish Bench in 1922. Tom's mother, the Honourable Nancy, was the youngest of eight children (six of them daughters) of Dick and Lizzie Atkin. Harold and Nancy married in 1933. It was Nancy's second marriage. Her first, to John Eve, had ended in divorce. John Eve (who was old enough to fight in both World Wars) and Harold Morison had one other thing in common, aside from marriage to Nancy: they had both gone to school at Winchester College. Tom Morison studied there too, and then at Worcester College, Oxford. He was called to the Bar by Gray's Inn in 1960, and in 1962 he joined what is now Fountain Court Chambers, in the Temple. (The set was located a few hundred yards away in Crown Office Row when Morison was recruited: it moved next to the iconic fountain in the 1970's.)

Dick Atkin had avoided narrow specialism in his career at the Bar, mixing tort cases and Workmen's Compensation Act claims with commercial actions. His grandson also maintained a varied practice. Fountain Court generally placed increasing emphasis on commercial litigation during the 1960's, reflecting the practice profiles of several members who were prominent in the field, including future Commercial Judges Thomas Bingham and Mark Waller. But the set had been founded on a much broader-based caseload, extending from crime to family disputes, and it retained a general common law dimension into the 1970's.

Morison's career at Fountain Court followed in this tradition. He appeared as counsel in cases involving matters as diverse as the quantification of fatal accidents claims relating to the Staines air disaster, Britain's deadliest accidental air crash, in which 118 people were killed when BEA Flight 548 stalled on take-off (Kandalla v BEA [1981] QB 158); a local authority's statutory housing liabilities (R v Secretary of State ex parte Enfield (1993) 26 HLR 51); judicial review of the independent television regulator's decisions (R v ITC ex parte TSW [1996] EMLR 291; and the treatment of pension rights in actuarial calculations for damages for personal injury (Auty v National Coal Board [1985] 1 WLR 784: Morison's reported cases suggest a niche expertise in litigation involving fiendishly complicated arithmetic.)

Tom Morison’s judicial grandparents: Lord Atkin (1867 - 1944) and Lord Morison (1868 - 1945)

Morison was junior counsel to Bingham in Birkett v James [1978] AC 297, a landmark case in procedural law, in which the House of Lords established the test for striking cases out for want of prosecution. They were supported by their chambers colleague Andrew Smith, another future Commercial Judge, but their clients lost, in spite of the strength of the counsel team. Morison and Smith lost in the Lords again in D v NSPCC [1978] AC 171, which established that public interest immunity from disclosure attached to reports to the charity of child abuse: this time, Bingham was on the other side.

Morison enjoyed greater success in Drexl v El Nasr [1986] 1 Lloyd's Rep 356, winning a commodities exchange case before Christopher Staughton in the Commercial Court. Commercial litigation was not a major component of Morison's practice however, although he did acquire some ship-related litigation experience acting for the plaintiff in a case in which a shipyard ultimately admitted infringement of copyright in the design of a warship.

But Morison was most prominent in employment disputes, and employment law accounts for by far the greatest number of his reported cases as counsel. These include several appearances in John Donaldson's controversial National Industrial Relations Court. In Secretary Of State v ASLEF [1972] 2 QB, Morison and his leader persuaded Donaldson, and also Lord Denning's Court of Appeal, that it was a breach of the contract of employment for rail workers to comply with their union's instructions to work to rule. This was just the sort of outcome which made the Industrial Relations Court, and the trade union legislation which was applied there, so deeply unpopular on the left wing of British politics, and the incoming Labour government of 1974 promptly abolished the whole system. But Morison seamlessly transitioned to regular appearances in high-profile cases before the newly-created the Employment Appeal Tribunal. In Simmons v Hoover [1977] QB 284, he effectively replicated the ASLEF decision, notwithstanding the legislative changes, with his successful argument that an employer was entitled to sack an employee for going on strike.

Morison's employment practice brought him into contact with a wide variety of industries, trades, and professions, including the railways, teaching, television, the press, and banking, and it covered a comprehensive spectrum of industrial relations issues: strikes, pensions, sex and age discrimination, wrongful dismissal, transfer of undertakings, union representation, closed shops, and injunctions to restrain industrial action. There was a European law dimension to some of these cases, but that aspect does not seem to have engaged his interest much: he argued Garland v British Rail [1983] 2 AC 751 on a discrimination point in the House of Lords, but did not follow the case to Luxembourg when their Lordships referred it to the European Court.

Over time, Morison came to represent employers rather more frequently than he did employees or their unions. The National Coal Board became a regular client. Morison won Dews v NCB [1988] AC 1 for them in the Lords. The case decided that an injured employee's right to compensation for lost earnings did not extend to a part of his gross pay which would have been deducted as a pension contribution in circumstances where his inability to work did not affect his pension rights: an early application, perhaps, of the now familiar "net loss" principle.

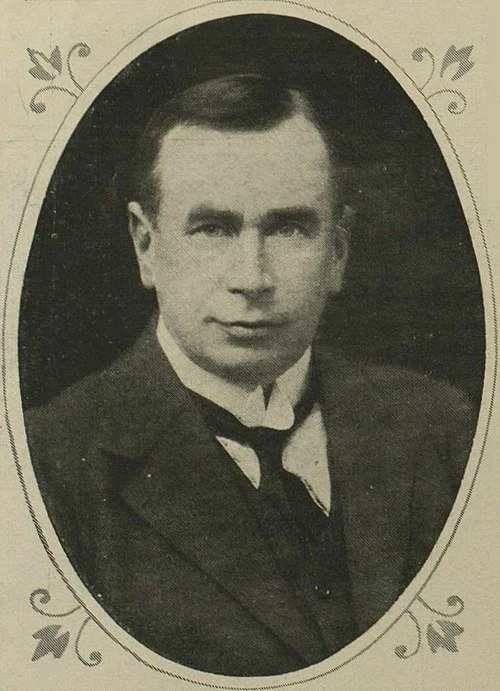

Mr Justice Morison

In 1986, seven years after he had been appointed Queen's Counsel, Morison enjoyed his most publicised success when he won for the Bar Council of England & Wales the right to a judicial review of the government's revision to the rates of pay for Legal Aid work. In a decision which made the front pages of the national press, the Court held that there was force in Morison's submission that the government had a duty to act rationally and that "figures can't be plucked out of the air". Lord Chancellor Hailsham swiftly agreed to negotiate terms with the Bar in what was widely seen as a tacit admission that, if the full judicial review went ahead, Morison would probably win that too. The selection of Morison to argue the case for the Bar was a manifestation of how highly regarded he was by his fellow professionals.

The Lord Chancellor's Department did not hold Morison's judicial review victory against him. In 1987, he was made a Recorder, a part-time judicial office which was traditionally a first step towards a career on the Bench. Within a fairly short time, he was sitting as a Deputy Judge in the High Court, and by the early 1990's, in a sign of how he saw his future, he was appearing in reported cases more frequently as judge than as counsel. His last significant outing at the Bar was in the heavyweight private international law dispute in Adams v Cape Industries in which, over thirty-five days in the Chancery Division and another eighteen days on appeal, he tried but failed to persuade the Court to enforce default judgments which had been entered in asbestos litigation in the US. The case remains a key authority on the circumstances in which English law will acknowledge that a foreign court has jurisdiction over a defendant.

Morison sat often in the Chancery Division in his capacity as Deputy Judge, trying a series of landlord and tenant cases, including one involving "a high-class jewellers" located in the foyer of the London Hilton (Montross v Moussaieff (1990) 61 P & CR 437). In Stuart v Barrett [1994] EMLR 448, he resolved an archetypal rock industry dispute between the members of a band and their former drummer. Striking a blow for the dignity of drummers everywhere, Morison declared that it was misconceived to think that they never made a meaningful contribution to song composition because they did not play a tuned instrument. One of Morison's cases as a Deputy reached the House of Lords: Stein v Blake [1996] AC 243. Sadly for Morison, their Lordships agreed with the Court of Appeal that he had got it wrong. But this setback did not hinder the upwards trajectory of Morison's career: by the time the Lords handed down their decision in spring 1995, he had already been a full-time Queen's Bench Judge for more than a year. When he took up judicial office in December 1993, he followed not only his two grandfathers, but also his older cousin on his father's side, Malcolm Morison, who had been appointed a Senator of the College of Justice in Scotland in 1985.

Morison was more closely involved with commercial litigation on the Bench than he had been at the Bar, delivering more than a hundred judgments in the Commercial Court over the full course of his judicial career, around thirty of which were thought worthy of a place in Lloyd's Law Reports. But employment cases remained his primary focus. After the traditional beginner's stint in the Criminal Division of the Court of Appeal (to give the novice the chance to learn by sitting with other judges: though Morison hardly needed hand-holding, with his extensive experience sitting on his own as a Deputy), he was swiftly deployed to the Employment Appeal Tribunal. He had been on the Bench for more than two years before he sat in a handful of Commercial Court cases in the first part of 1996. Not long after that experimental venture, he was appointed President of the Employment Appeal Tribunal, a demanding leadership position which left him no time to sit in any other Court, save for a few criminal cases. But Morison sat as Commercial Judge relatively frequently from the expiry of his term as President in 1999 until his retirement.

His most high-profile commercial case was Fiona Trust v Privalov, an "oligarch" dispute in which the issue was whether a claim that a contract had been validly rescinded for bribery fell within the scope of an arbitration clause contained within the very contract itself. The analysis by which Morison reached the conclusion that it did not was heavily semantic, perhaps even pedantic, yet had the virtue of being consistent with a significant body of previous authority. But the Court of Appeal was in a reforming mood, and the House of Lords even more so. In one of the leading judgments of modern arbitration law, Lord Hoffmann dismissed the authorities which Morison had faithfully sought to follow as "reflecting no credit upon English commercial law", and resolved to "make a fresh start", based upon a presumption of "one-stop adjudication" ([2008] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 254).

Morison's employment and commercial cases left limited scope for other types of dispute, and he sat in relatively few of the administrative law, personal injuries, and tort trials which formed a large part of the Queen's Bench Division's workload. But he shouldered his share of criminal cases, including in the Criminal Division of the Court of Appeal. He also helped out in the Civil Division in a handful of cases, including a landlord and tenant dispute in Lewisham v Masterson (1999), taking him back to his days as a Deputy. But Morison did not become a full-time member of the Court of Appeal: he was still at first instance when he retired in 2007. Since he had left the Bench well short of the compulsory retirement age, Morison was qualified to sit part-time as an additional Queen's Bench Judge. But he heard only a handful of cases before stopping for good in 2010. None were in the Commercial Court, and none were of any great legal interest, although R ex parte Stapleton v Revenue & Customs (2008) attracted press attention because the Claimant, who was seeking to prevent the Revenue from confiscating her home as the proceeds of a VAT fraud perpetrated by her father, had appeared in the TV soap 'EastEnders'. Morison found in her favour. (Morison's cousin Malcolm also served as a judicial "retread", after retiring from the Scottish Bench. He eventually refused to sit any more in protest as what he regarded as an over-reliance on part-timers and a failure to fund sufficient permanent posts.)

Like Anthony Colman, his contemporary on the Commercial Bench, Morison was plagued by barristers and solicitors, and the occasional law reporter, misspelling his surname. But he seldom allowed the insertion of a redundant extra "r", or anything else, to upset his courtroom demeanour. A good-natured and humorous individual who did not take himself excessively seriously, he was never harsh to counsel, no matter how bad their argument, and was a popular judge. He was also a good and respected one, with a usually reliable sense for the correct answer. His decisions were not often overruled, although his occasionally unguarded mode of expression sometimes caused consternation on appeal: his closing remarks in Fletamentos v Effjohn [1997] 1 Lloyd's Rep 295 appeared to imply that the London maritime arbitration community was populated by knuckle-dragging bigots, and the Court of Appeal felt constrained to emphasise that this "innuendo" was not justified by the evidence.

Retirement gave Morison time to indulge his passions for reading and cooking at his home near Devizes. He also loved gardening, and he chaired a not-for-profit organisation which planted different varieties of tree around Wiltshire.

Tom Morrison and his cousin Elizabeth Barry unveiling the plaque marking their grandfather’s Brisbane birthplace.

In 2021, Morison made a pilgrimage to Queensland to attend the unveiling of a plaque on the site of his grandfather Dick Atkin's birthplace at Tank Street, Brisbane. Appropriately enough, the city's Commonwealth Law Courts now stand on the spot. Morison's maternal grandmother, Atkin's wife Lizzie Hemmant, had been born about a hundred yards away and at almost the same time as Dick, and Dick and Lizzie had played together as children. Speaking at the ceremony, Morison described how Atkin's parents were almost shipwrecked during the long months of the sea journey from Wales to Australia. They had survived that ordeal only for Atkin's father to die of consumption within a few years of their safe arrival. Eventually, both the surviving Atkins and the Hemmants had ended up in Britain, which was where Dick and Lizzie married and raised their family, including Morison's mother, Nancy.

Like Nancy, Morison was twice married and once divorced. He and his first wife had a son and a daughter.

Thomas Richard Atkin Morison died from cancer in March 2022. Knowing that the end was coming, he wrote his own death notice. It was published in The 'Times' on April Fool's Day: the timing would probably have appealed to him. As the tribute published by his old chambers said, the text gave a glimpse of his mischievous sense of humour and complete want of pomposity.

Morison, Thomas Richard Atkin: Snuffed it on 19th March, aged 83. No funeral; no memorial; no mourning; no flowers; no worries. Grateful thanks to the cancer team at the neurological-oncology centre, Southampton. With huge thanks to my wonderful wife for caring for me so well; to my wonderful children: thank you especially for giving me four beautiful and talented granddaughters. And thanks to my furry four-footed friend, Dave: sorry I was not a better walker for you at the end. Just perhaps, see you all later…"